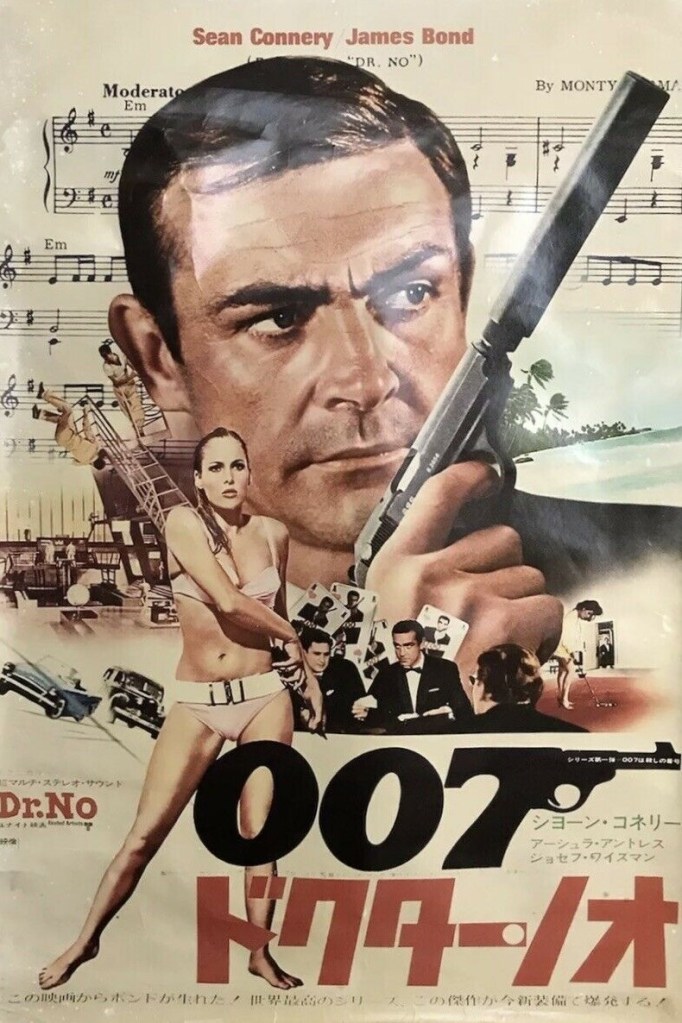

Minus the gadgets and the more outlandish plots, the James Bond formula in embryo. With two of the greatest entrances in movie history – and a third if you count the creepy presence of Dr No himself at the beds of his captives – all the main supporting characters in place except Q, plenty of sex and action, plus the credit sequence and the theme tune, this is the spy genre reinvented.

Most previous espionage pictures usually involved a character quickly out of their depth or an innocent caught up in nefarious shenanigans, not a man close to a semi-thug, totally in command, automatically suspicious, and happy to knock off anyone who gets in his way, in fact given government clearance to commit murder should the occasion arise. That this killer comes complete with charm and charisma and oozes sexuality changes all the rules and ups the stakes in the spy thriller.

Three men disguised as beggars break into the house of British secret service agent Strangeways (Tim Moxon) and kill him and his secretary and steal the file on Dr No (Joseph Wiseman). A glamorous woman in a red dress Sylvia Trench (Eunice Gayson) catches the eye of our handsome devil “Bond, James Bond” (Sean Connery) at a casino before he is interrupted by an urgent message, potential assignation thwarted.

We are briefly introduced to Miss Moneypenny (Lois Maxwell) before Bond is briefed by M (Bernard Lee) and posted out immediately – or “almost immediately” as it transpires – to Jamaica, but not before his beloved Beretta is changed to his signature Walther PPK and mention made that he is recovering from a previous mission. But in what would also become a series signature, liberated women indulging in sexual freedom, and often making the first move, Ms Trench is lying in wait at his flat.

Another change to the espionage trope, this man does not walk into the unknown. Suspicion is his watchword. In other words, he is the consummate professional. On arrival at Jamaica airport he checks out the waiting chauffeur and later the journalist who takes his picture. The first action sequence also sets a new tone. Bond is not easily duped. Three times he outwits the chauffeur. Finally, at the stand-off, Bond employs karate before the man takes cyanide, undercutting the danger with the mordant quip, on delivering the corpse to Government house, “see that he doesn’t get away.”

Initially, it’s more a detective story as Bond follows up on various clues that lead him to Quarrel (John Kitzmiller), initially appearing as an adversary, and C.I.A. agent Felix Leiter (Jack Lord) before the finger of suspicion points to the mysterious Dr No and the question of why rocks from his island should be radioactive. Certainly, Dr No pulls out all the stops, sending hoods, a tarantula, sexy secretary Miss Taro (Zena Marshall) and the traitor Professor Dent (Anthony Dawson) to waylay or kill Bond.

But it’s only when our hero lands on the island and the bikini-clad Honey Rider (Ursula Andress) emerges from the sea as the epitome of the stunning “Bond Girl” that the series formula truly kicks in: formidable sadistic opponent, shady organization Spectre, amazing sets, space age plot, a race against time.

It’s hard not to overstate how novel this entire picture was. For a start, it toyed with the universal perception of the British as the ultimate arbiters of fair play. Yet, here was an anointed killer. Equally, the previous incarnation of the British spy had been the bumbling Alec Guinness in Our Man in Havana (1959). That the British should endorse wanton killing and blatant immorality – remember this was some years before the Swinging Sixties got underway – went against the grain.

Although critics have maligned the sexism of the series, they have generally overlooked the female reaction to a male hunk, or the freedom with which women appeared to enjoy sexual trysts with no fear of moral complication. Bond is not just macho, he is playful with the opposite sex, flirting with Miss Moneypenny, and with a fine line in throwaway quips.

Director Terence Young is rarely more than a few minutes away from a spot of action or sex, exposition is kept to a minimum, so the story zings along, although there is time to flesh out the characters, Bond’s vulnerability after his previous mission mentioned, his attention to detail, and Honey Rider’s backstory, her father disappearing on the island and her own ruthlessness. The insistently repetitive theme tunes – from Monty Norman and John Barry – was an innovation. The special effects mostly worked, testament to the genius of production designer Ken Adam rather than the miserable budget.

Most impressive of all was the director’s command of mood and pace. For all the fast action, he certainly knew how to frame a scene, Bond initially shown from the back, Dr No introduced from the waist downwards, Honey Rider in contrast revealed in all her glory from the outset. The brutal brief interrogation of photographer Annabel Chung (Marguerite LeWars), the unexpected seduction of the enemy Miss Taro and the opulence of the interior of Dr No’s stronghold would have come as surprises. Young was responsible for creating the prototype Bond picture, the lightness of touch in constant contrast to flurries of violence, amorality while blatant delivered with cinematic elan, not least the treatment of willing not to say predatory females, the shot through the bare legs of Ms Trench as Bond returns to his apartment, soon to become par for the course.

Future episodes of course would lavish greater funds on the project, but with what was a B-film budget at best by Hollywood standards, the producers worked wonders. Sean Connery (The Frightened City, 1961) strides into a role that was almost made-to-measure, another unknown Ursula Andress (The Southern Star, 1969) speeded up every male pulse on the planet, Joseph Wiseman (The Happy Thieves, 1961) provided an ideal template for a future string of maniacs and Bernard Lee (The Secret Partner, 1961) grounded the entire operation with a distinctly British headmaster of a boss.

Masterpiece of popular cinema.