“Up to his clavicle in whimsicality,” is the best I can do. While acknowledging that quote is not mine, I should also make clear it could apply to any Wes Anderson picture. He strikes me as critic-proof. With a hard core of fans, whether his movies enter box office heaven depends on the oldest and most elusive of marketing tricks: word-of-mouth.

I am going to be telling everyone to go-see without really being able to explain why they should. I might not be able to describe the plot without putting everyone off. I might get the plot wrong. Ostensibly, it’s about a bunch of disparate characters coming together in the titular city (pop: 87!!) to celebrate in the mid-1950s the gazillionth anniversary of the landing of an asteroid, a pock-marked rock about the size of a giant watermelon.

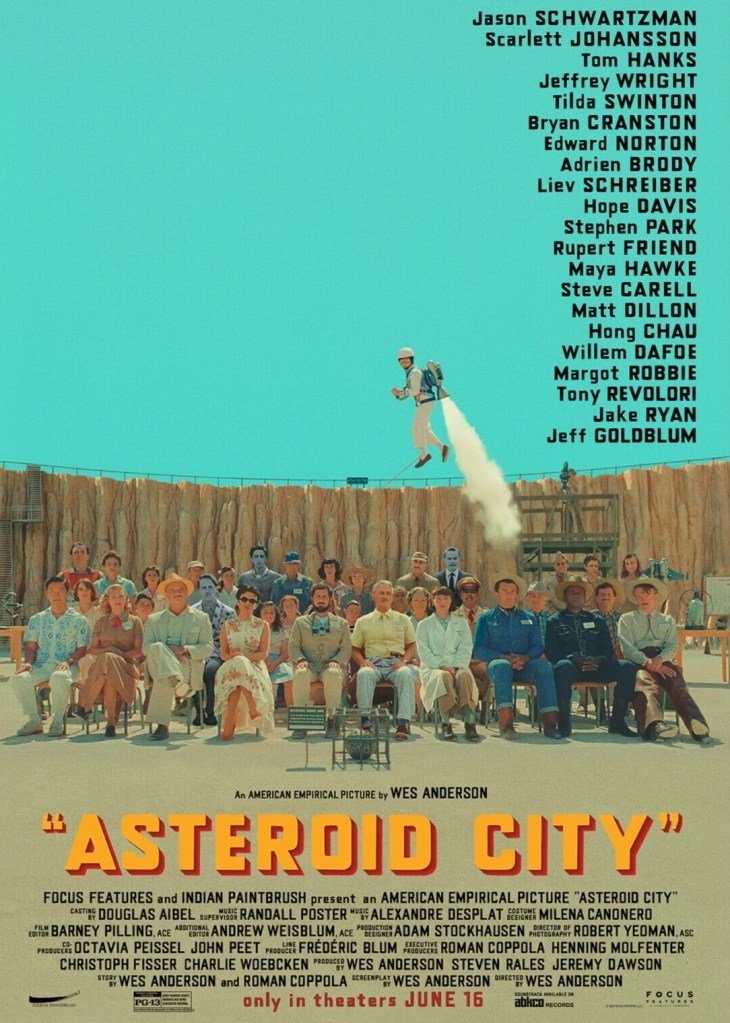

The motley crowd includes scientists, U.S. Army representatives, schoolkids taking part in a science competition, sightseers and some characters stranded there and, halfway through, an alien who commits the heist of the century, though unlike most caper pictures there’s none of the usual pre-robbery set-up.

While Anderson has a consistency of outlook that delights/bewilders/infuriates critics, he has a stunning sense of originality. He doesn’t repeat himself and reveals an astonishing freshness when it comes to the myriad methods employed to tell a story. At least here, the narrative is, roughly, straightforward not breaking off into various routes (or even cul de sacs) as in his previous outing The French Dispatch, which struggled in the old word-of-mouth department but which I adored.

To help me along here with what the film was all about I looked up the lead review in Imdb. Not only was it no help at all, it was pretty dispiriting. Poor old Wes Anderson gets walloped for lack of plot. I couldn’t care tuppence for plot as long as I’m entertained. And I went along quite happily with the ultra-post-ironic (post-something anyway) notion that we were watching the filmed version of a famous play or possibly the situation which inspired the play but cutting between both and the actors in the movie version not only playing characters but dropping into their genuine personalities – or perhaps not, maybe these were the characters from the play.

And here, the last thing I want to do is put you off. So, yeah, if you think narrative isn’t just watching a bunch of people who’ve never met before interact, a category into which I guess you would chuck movies as different as The Towering Inferno (1974) and Titanic (1997), and think they have to be gathered for a doomsday scenario, and ignore the likes of Bus Stop (1956) then just go ahead and talk yourself out of that rare sighting on the Hollywood hills, an adult movie with nary a superhero (discounting said alien of course, whose back story might include super-heroism for all I know) involved.

This might just be one long litany of jokes, but why would you complain about that? Anyway, for the sake of anyone who has come here for a proper review, here goes.

Grieving widower Augie (Jason Schwartzmann) is unexpectedly stuck in Asteroid City when his car goes into meltdown. His three young children think they are auditioning for Macbeth, constantly casting spells and intent on burying their mother’s ashes, contained in a Tupperware bowl, in the desert, and generally acting weird. His equally widowed father-in-law Stanley (Tom Hanks), dressed as if coming straight from the golf course, turns up to pretty much tell him how much he dislikes him. Augie has a short affair with movie star Midge (Scarlett Johansson) while her science-minded daughter gets to experience first love and proves a whiz at some extremely complicated memory game that I might have played when young but can’t remember the name of or which could equally be a Wes Anderson invention.

Please sir, that’s as much plot as I can remember. Various other characters appear, flitting in and out, and don’t behave as you might expect. Oh, some do, there’s a hotel owner selling plots of real estate, but there’s also the apparently straight from Central Casting General Gibson (Jeffrey Wright) whose speech sounds more like an elevator pitch for a novel. See, I told you, explaining it won’t help. You just gotta go see it.

You might spend the whole picture rubber-necking, spotting stars in cameo roles, but except for Edward Norton and to some extent Tilda Swinton none of them are doing what they are famous/infamous for. Maybe Wes Anderson has a constant queue of A-list applicants for small roles just because a) they get to play someone completely different from normal and/or b) they get to work with the great man.

Roman Coppola (Moonrise Kingdom, 2012) was drafted in to help write the screenplay maybe just so the director can get to share the blame if it’s a critical dog.

Go see.

Did I already say that?