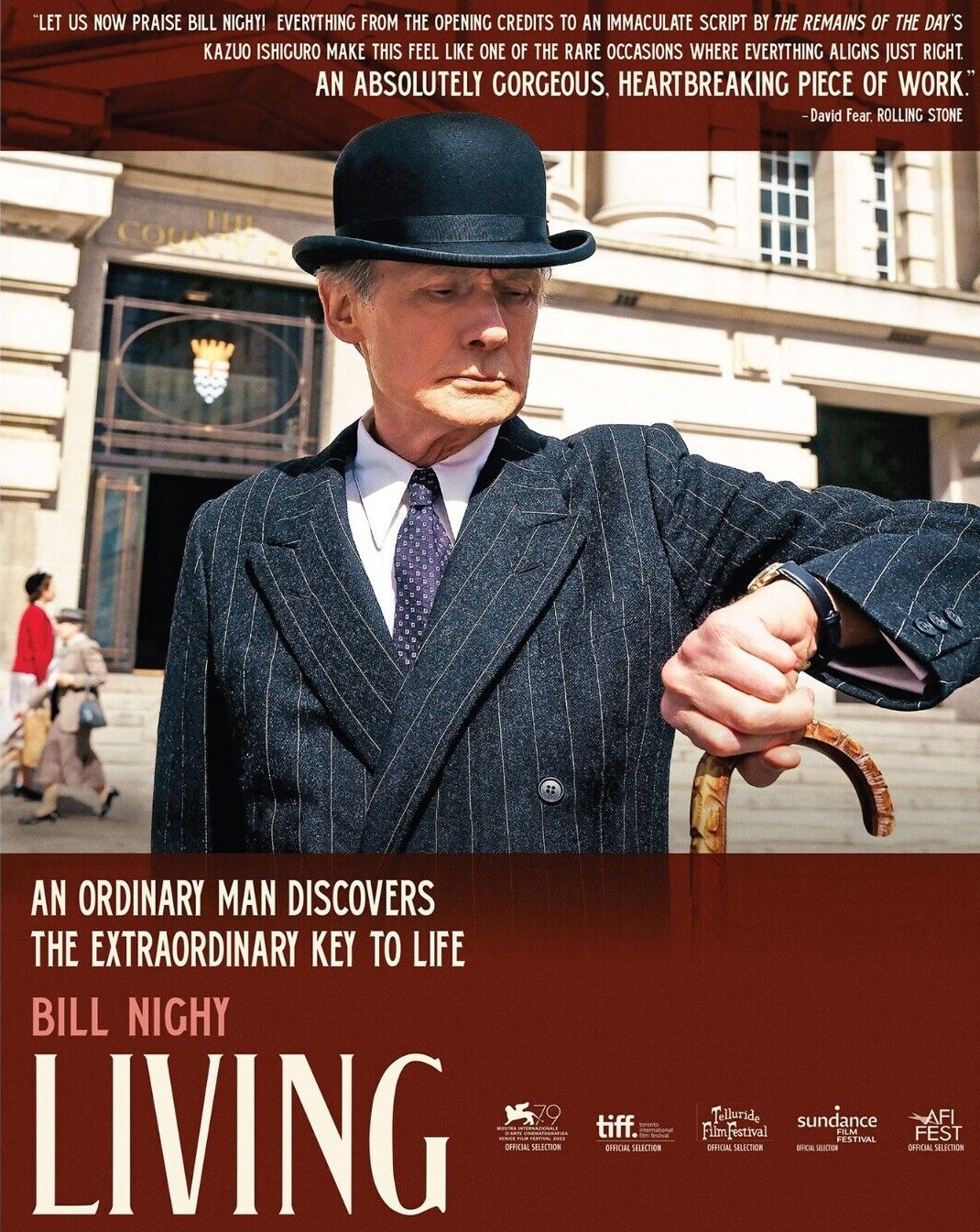

Luckily I had been fortified in my weekly cinema outing by the wonderful Living (2022) before entering dudsville for this double bill. Both Deus and Watcher have all the hallmarks of direct-to-DVD productions which have, to use the old parlance, “escaped” into cinema distribution.

I’m probably a bit rusty about the cost of making the kind of giant spacecraft shown in Deus, billions of dollars surely, so am assuming that big projects like this will encounter budget overruns which would account for the rationing of electricity on board, resulting in the murky lighting. And there’s not an alien in sight unless you count the robotic crew who speak in strangely monotonous tones.

Like most sci-fi films this involves a crew on a mysterious mission awaking from hibernation to investigate a distant object, in this case a sphere. The title assumes this might be about someone playing God and so it transpires, taking a leaf out of The Avengers: Infinity War (21018) playbook with a plot to wipe out three-quarters of the Earth’s population in some kind of eco good deed.

Not only has an evil genius Vance (Phil Davis), who appears only as a hologram (natch), gone to all this bother and created a heavenly apparition but in order to achieve his ends he has had to go to all the clever bother of killing off the family of Karla (Claudia Black) in a car crash so that he can have the opportunity to insert a chip in her brain to infiltrate her imagination.

Former hitman Ulph (David O’Hara) forms part of the crew and the only measure of excitement comes when, mercifully, parts of the mother ship explode. Any action or suspense is purely theoretical with writer-director Steve Stone (In Extremis, 2017) responsible for this monstrosity.

It’s a terrible thing to say I know but I was praying for the serial killer to get a move on and wipe out dull lifeless heroine Julia (Maika Monroe) in Watcher. A former actress, now unemployed, who has moved to Bucharest with advertising executive partner Francis (Karl Glusman) she spends all her time moping around crying wolf. Naturally, everyone ignores her if only for the fact that when she claims to be watched by a man from across the street she has facilitated such voyeurism by leaving her curtains wide open.

The serial killer is known as The Spider for obvious reasons – I guess he has either a hairy back, six arms, climbs up the outside of buildings, or is the type of arachnid who bites the head off his victims or all of the above or because newspaper headline writers had run out of murderer nicknames or were simply devoid of imagination.

As with Matt Damon in Stillwater (2021) her sense of isolation, what with hubby working all hours, is increased because only a tiny minority of the population have the courtesy to speak English. Location-wise you know where this is going to end up because next door neighbor Irina (Madalina Anea) keeps a gun in a drawer in case her ex gets antsy, making him of course the first red herring.

For a time it looked as if this was going to turn into something a lot more interesting, a twist on a twist, for in fact she is as much a watcher as the man (Burn Gorman) – a cleaner in a strip club who stares out of the window in a break from the relentless task of caring for his aged father – accused of this crime. In a very foolish gesture she appears to be encouraging him.

You begin to hope that, to redeem this picture, the upshot is going to be that a paranoid woman shoots an innocent man. Instead, the climax is straight of Hancock’s Half Hour, a legendary British television comedy series, where the heroine survives after losing more than a good armful of blood, probably enough to fill all arms, legs and the bulk of her body.

Maika Monroe (It Follows, 2014) has gone with the erroneous assumption that the less acting she does the more she will appear withdrawn. I felt sorry for Karl Glusman (Greyhound, 2020) in his first leading man role, given nothing to do. Oddly enough, Burn Gorman (Pacific Rim, 2013) has the best scene, demanding an apology from his accuser.

I’m not quite sure what debut director Chloe Okuna did to the original screenplay of the more experienced Zack Ford (Girls’ Night Out, 2019) to grab the main writing credit but it was far from enough.

Like The Banshees of Inisherin, too much appears to be expected of both writer-directors who might have benefitted from a stronger producer challenging their concepts and helping shape the finished material.