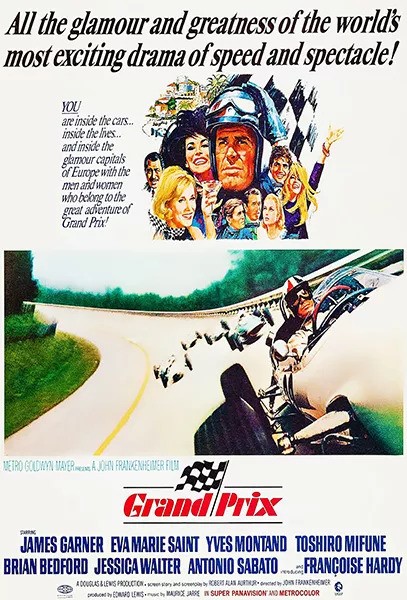

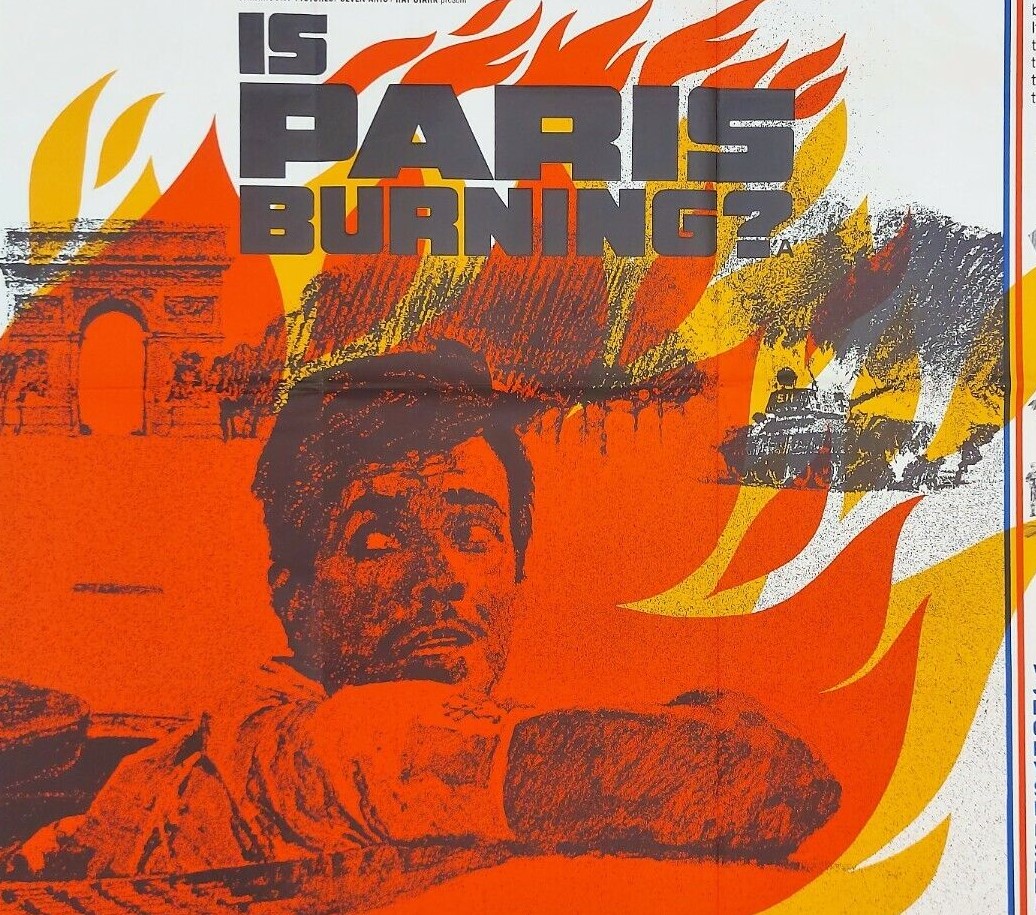

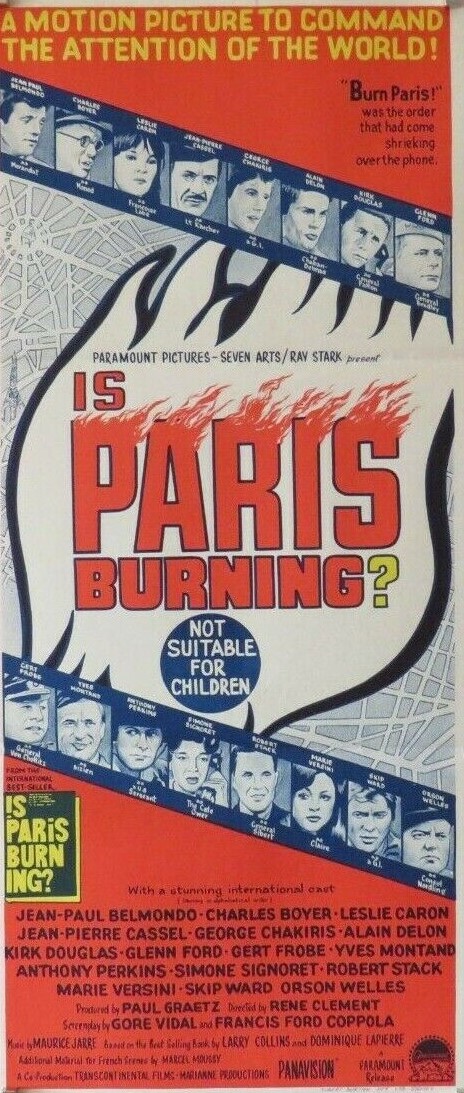

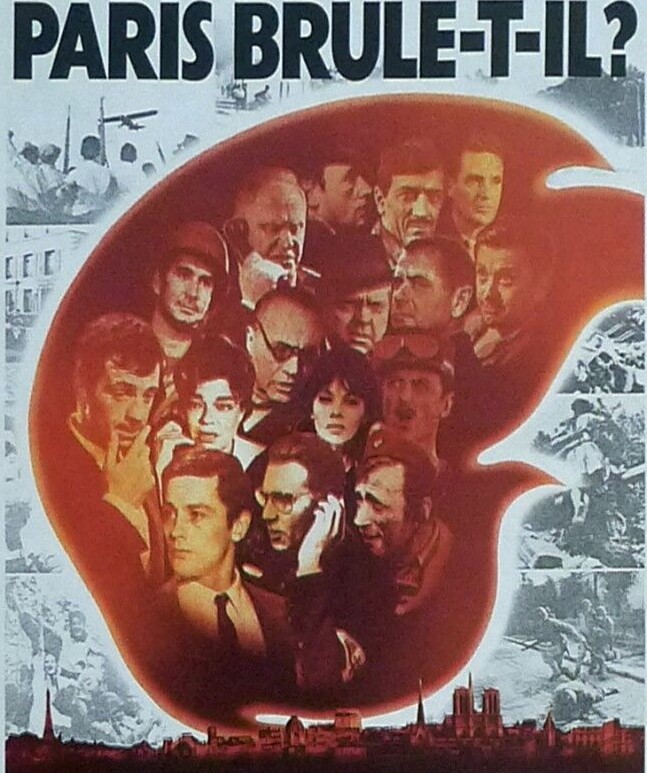

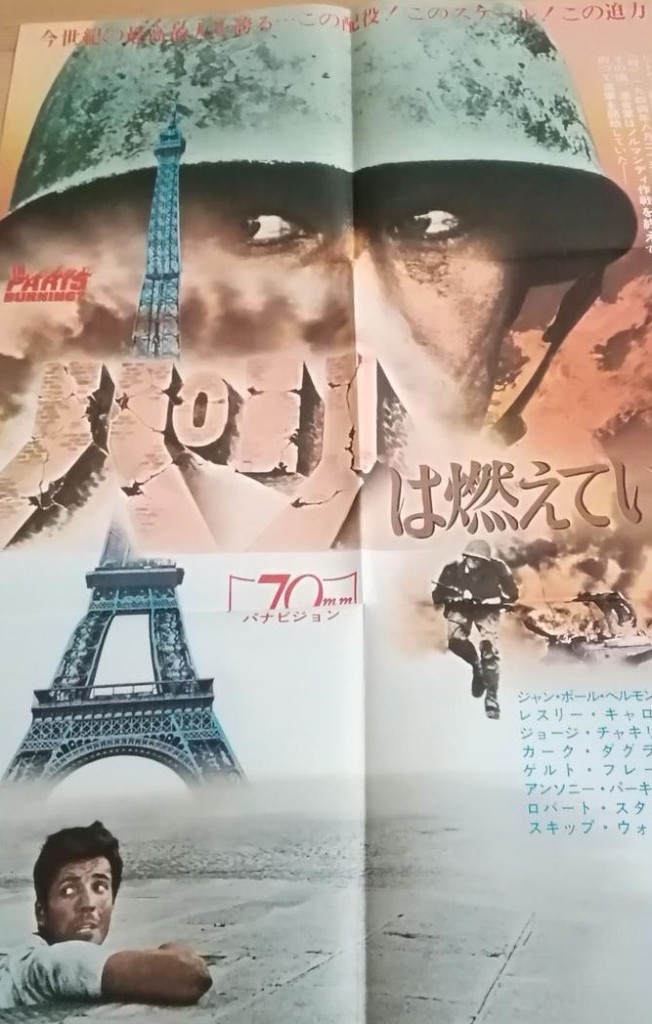

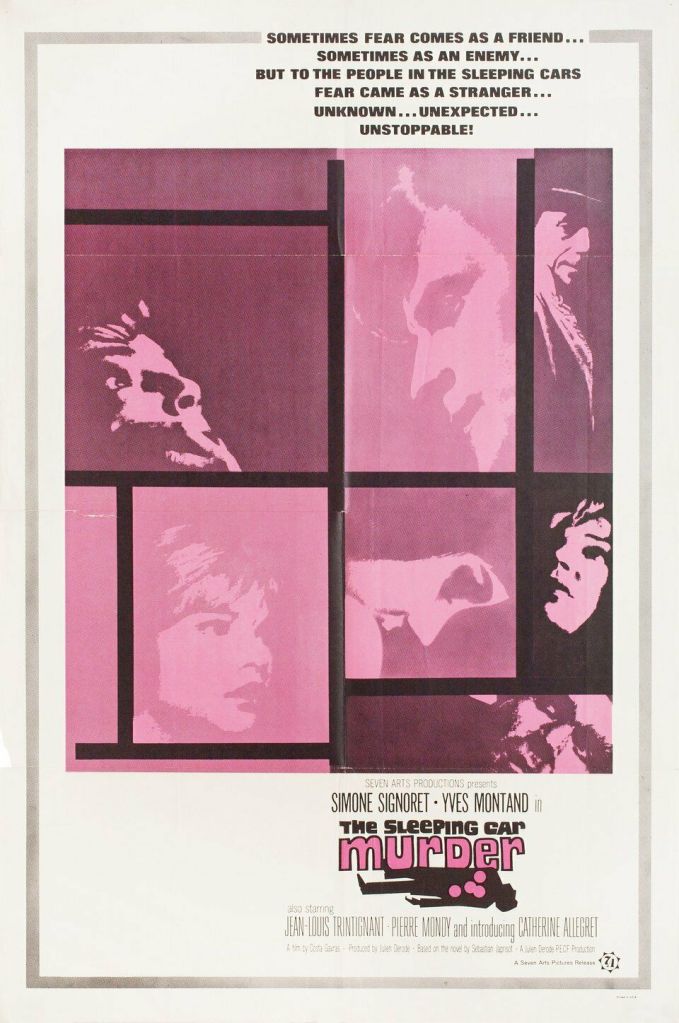

Absolutely brilliant thriller. Even after a half a century, still a knock out. A maniac on the loose, baffled cops, glimpses into the tattered lives of witnesses, victims and relatives, told at break-neck speed by Greek director Costa-Gavras (Z, 1969) on his debut and concluding with an astonishing car chase through the streets of Paris. Not just an all-star French cast – Yves Montand (Grand Prix, 1966), Oscar-winner Simone Signoret (Is Paris Burning?, 1966), Jean-Louis Trintignant (Les Biches, 1968) and Michel Piccoli (Topaz, 1969) – but directed with a Georges Simenon (creator of Maigret) sensibility to the frailties of humanity.

As well as the twists and turns of the narrative, what distinguishes this thriller are the parallel perspectives. Where most whodunits present an array of suspects, inviting the audience to work out the identity of the killer, here virtually all the characters are presented both objectively and subjectively. Some are delusional, others highly self-critical, occasionally both, and we are given glimpses into their lives through the characters’ internalized voice-over and dialog.

Tiny details open up worlds – the wife of a dead man bewailing that he would not be able to wear the fleecy shoes she had just bought him to keep out the cold during his night-time job, a policeman revealing he wanted to be a dancer, a vet who wants to create a new breed of animals, a witness whose parents committed suicide. But just as many, the flotsam and jetsam of the police life, irritate the hell out of the cops: Bob Valsky (Charles Denner) constantly berates their efforts, relatives bore the pants off their interviewer, not to mention self-important police chief Tarquin (Pierre Mondy) who has an answer for everything.

A young woman Georgette (Pascale Roberts) is discovered dead in the second-class sleeper compartment of a train after it has pulled into Paris. Initial suspicion falls on the other occupants including aging actress Eliane (Simone Signoret) in the thrall of her much younger lover Eric (Jean Louis Trintignant), impulsive blonde bombshell Bambi (Catherine Allegret), low-level office worker Rene (Michel Piccoli) and Madame Rivolani (Monique Chaumette). Weary Inspector Grazziani (Yves Montand), suffering from a cold and wanting to spend more time with his family, is handed the case. But before he can interview the suspects, they start getting knocked off.

So convinced are the police of their own theories that they ignore the testimony of Eliane and instantly home in on fantasist Rene, treated with contempt, a dishevelled lecherer who on the one hand misinterprets signals from women and on the other realizes that no one in their right mind would ever date him. Eliane is tormented by the prospect of being abandoned by her controlling lover.

It’s a race against time to find the passengers before the killer. In the middle of all this there is burgeoning romance between Bambi and clumsy mummy’s boy Daniel (Jacques Perrin), who may well hold the key to the murders. Their meet-cute is when he ladders her stockings.

I won’t spoil it for you by listing all the red herrings, surprises, mishaps, tense situations and explorations of psyche, but the pace never abates and it keeps you guessing to the end. And while all that keeps the viewer on tenterhooks what really makes the movie stand out is the depiction of the inner lives of the characters.

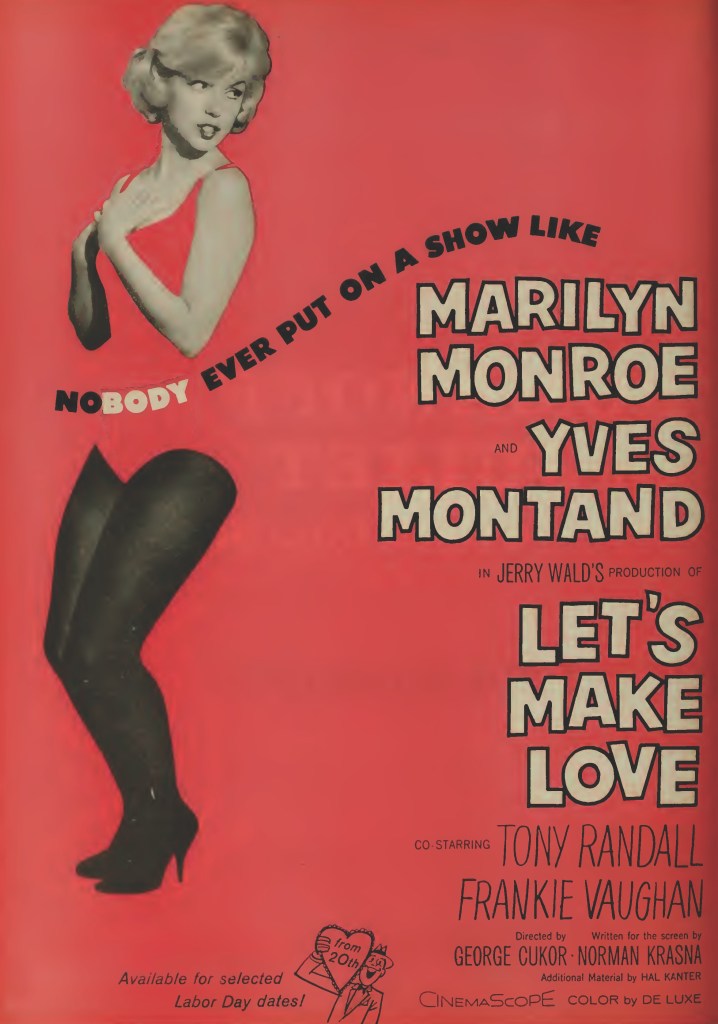

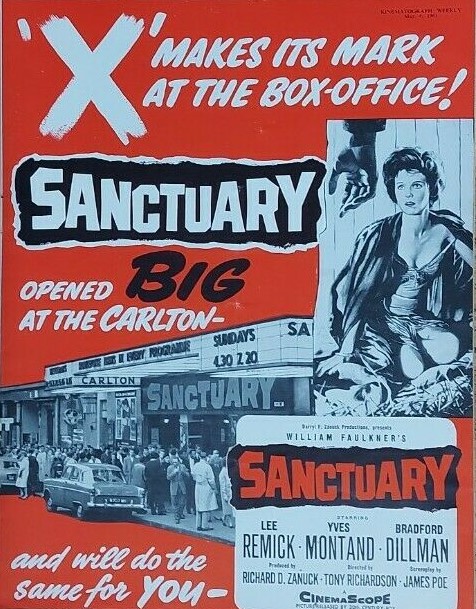

So often cast as a lover Yves Montand is outstanding as the diligent cop. Signoret captures beautifully the life of a once-beautiful woman who now enjoys the “empty gaze of men,” Trintignant essays a sleazier character than previously while Michel Piccoli who often at this stage of his career played oddballs invites sympathy for an unsympathetic character. Catherine Allegret (Last Tango in Paris, 1972) and Jacques Perrin (Blanche, 1971) charm as the young lovers. In tiny roles look out for director Claude Berri (Jean de Florette, 1986), Marcel Bozzuffi (The French Connection, 1971) and Claude Dauphin (Hard Contract, 1969),

Costa-Gavras constantly adds depth to the story and his innovative use of multiple voice-over, forensic detail, varying points-of-view, plus his masterful camerawork and a truly astonishing (for the time) car chase points to an early masterpiece. Sebastian Japrisot (Farewell, Friend / Adieu L’Ami, 1968) wrote the screenplay based on his novel.

Can’t remember where I got my DVD, perhaps second-hand, but there is an excellent print, taken from the 2016 restoration, available on YouTube.