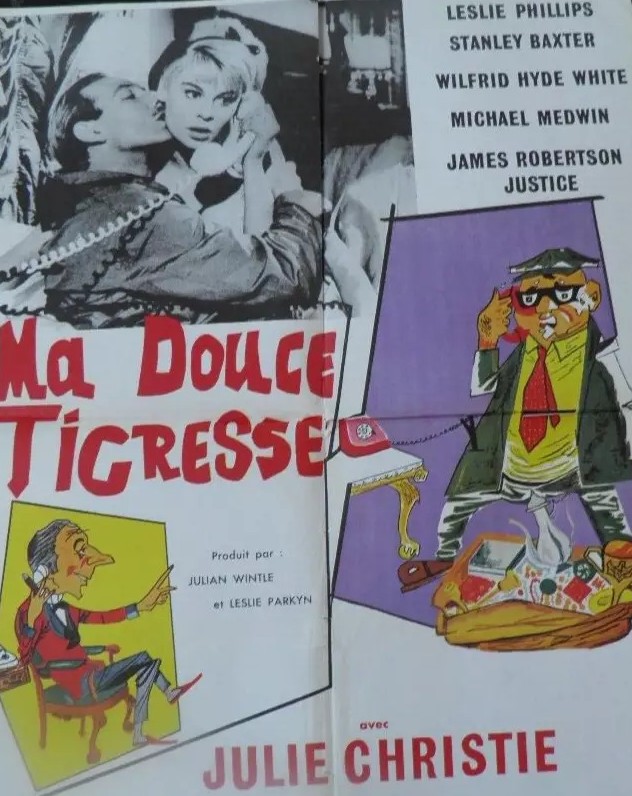

Charm was in short supply in the 1960s. Sure, for a period you still had Cary Grant but David Niven was as often to be found in an action picture (The Guns of Navarone, 1961) or a drama, and others of the ilk, like Tony Curtis, veered more towards outright comedy. Britain had something of what would today be called a “national treasure,” admittedly a term more likely to be accorded females of the standing of Maggie Smith or Judi Dench; maybe a space might be found for the idiosyncratic Ralph Richardson. Dare I put Leslie Phillips into contention for such an honor?

Once into his mellifluous stride and with his trademark appreciation of female beauty, “Ding dong!” a more welcome remark than the more common “Cor!” or “Strewth” or sheer inuendo, Leslie Phillips, not so well known perhaps in the USA and foreign parts, would fit that definition. He had charm in spades.

Unfortunately, you could split his career into those roles where “ding dong” entered the equation and those it did not. This is one of those, and I have to confess I’m both disappointed and delighted. Dissatisfied because the charm appeared part of his screen persona, but pleased whenever I found out he wasn’t tied down to it and could essay other characters just as well.

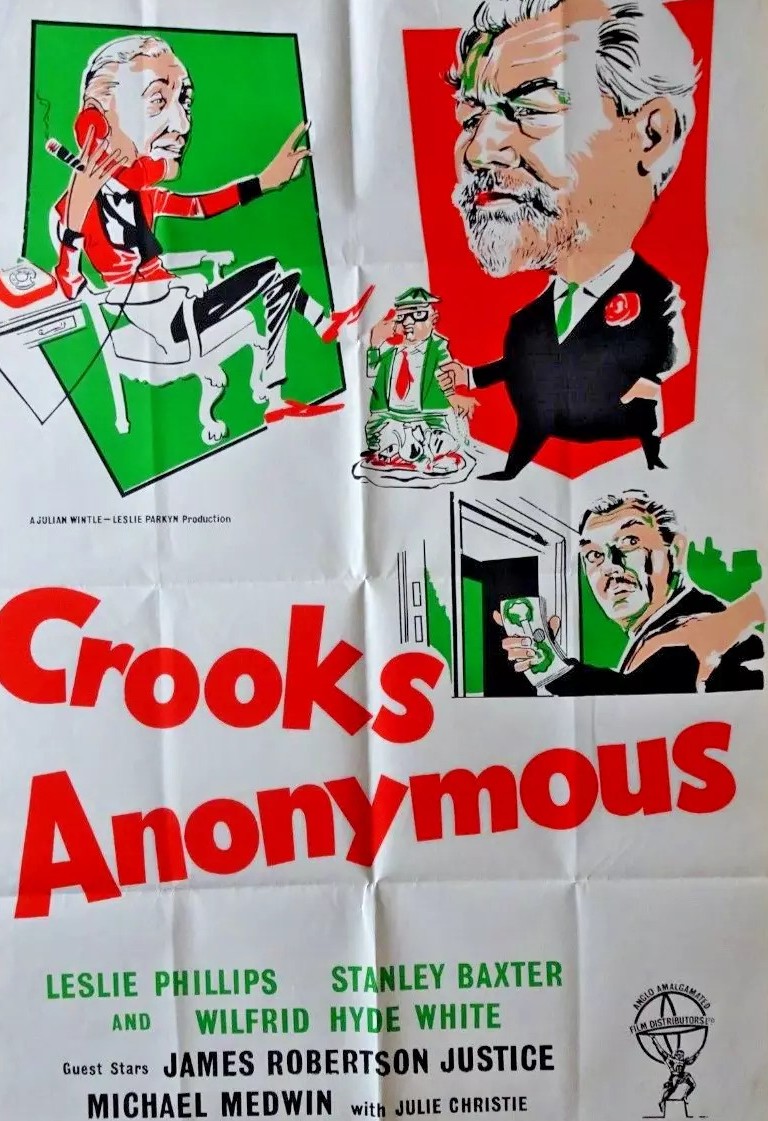

Here, here’s shifty criminal Dandy, whose only redeeming feature is that somehow he has acquired a beautiful girlfriend, stripper Babette (Julie Christie), who, despite her profession

appears to have steered cleared of seediness and insists he goes straight before she consents to marriage. And that would be fine, except what can Dandy do when faced with such obvious temptation and jewels left idly on a counter in a jewellery?

When she catches him out, he is sent to the criminal version of Alcoholics Anonymous where he is at the mercy of a particularly sadistic “guardian angel” Widdowes (Stanley Baxter – in a variety of disguises). He is locked in a cell full of safes. Food, cigarettes etc are hidden inside the safes, so to eat and satisfy his smoking habit, he must open them. The logic, presumably, is that he will grow sick and tired of opening so many safes for so little reward.

Maybe it’s the hidden punishments – a touch of electrocution and various other booby traps – that do the trick. Or, it could be the glee of Widdowes. When Dandy finds cigarettes, they come without any means of lighting them. He pleads with Widdowes to point him in the direction of a safe containing means of ignition.Replies the “angel”, “I’m glad you asked that because I’m not going to tell you.”

There’s a whole raft of comedy skits revolving around temptation, mostly involving Widdowes in one guise or another. And when the movie stays with Widdowes and a bunch of other reformed criminals, it fairly zips along. But once Dandy is released and plot rears its ugly head it falls back on more cliché elements.

Dandy manages to go straight, employed as a Santa Clause in a department store, while Babette decides to give up her job so both can start afresh. Unfortunately, temptation raises its ugly head to the tune of a quarter of a million pounds and all those goody-two-shoes reformed criminals line up to take a crack at it. The twist, which you’ll already have guessed, is that they have to break into the vault again to return the money they have stolen.

Scottish comedian Stanley Baxter was going through a phase of attempting to become a movie star and was given a fair old crack at it – The Fast Lady (1962) and Father Came Too (1964) followed, the former with both Philips and Christie, the latter with just him.

But what was obvious from Crooks Anonymous was that Baxter was better in disguise – and the more the merrier – than served up straight. He steals the show here where in the other movies his character is more of an irritant.

A well-meaning Leslie Phillips somehow snuffs out the charm and there’s not enough going on between him and Babette when he’s full-on straightlaced. Heretical though it might be, there’s not enough going on with Julie Christie either to suggest she might be Oscar bait. Here’s she’s just another ingenue.

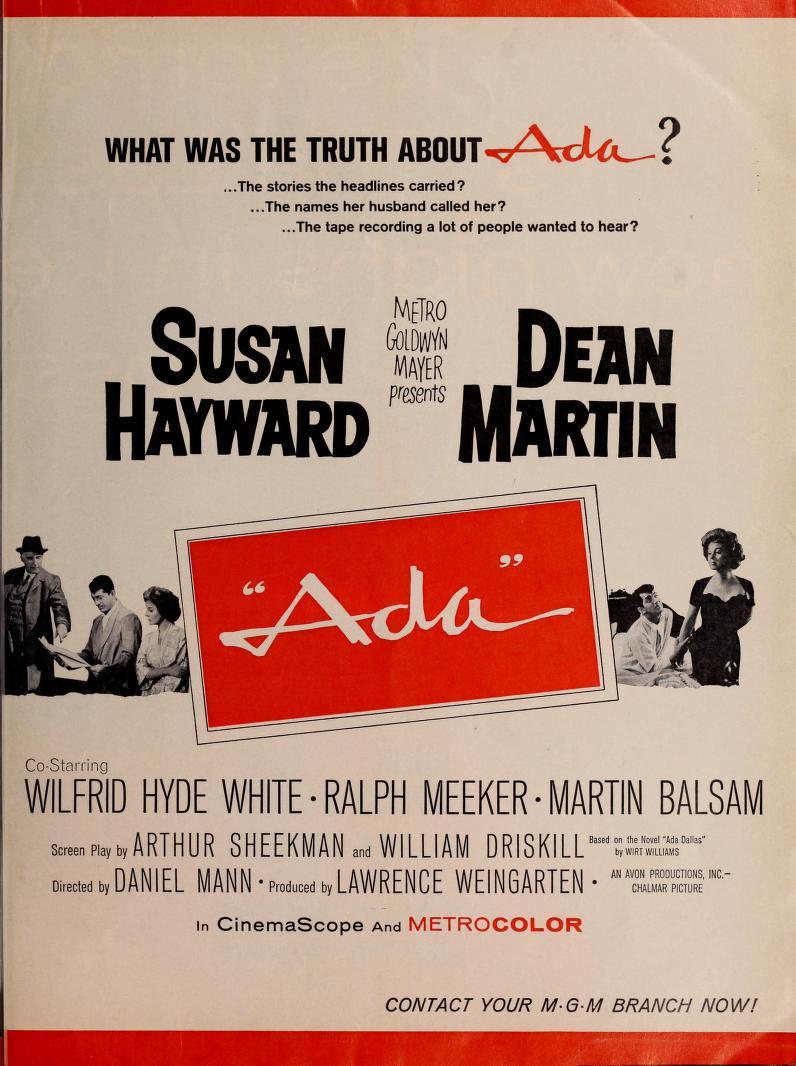

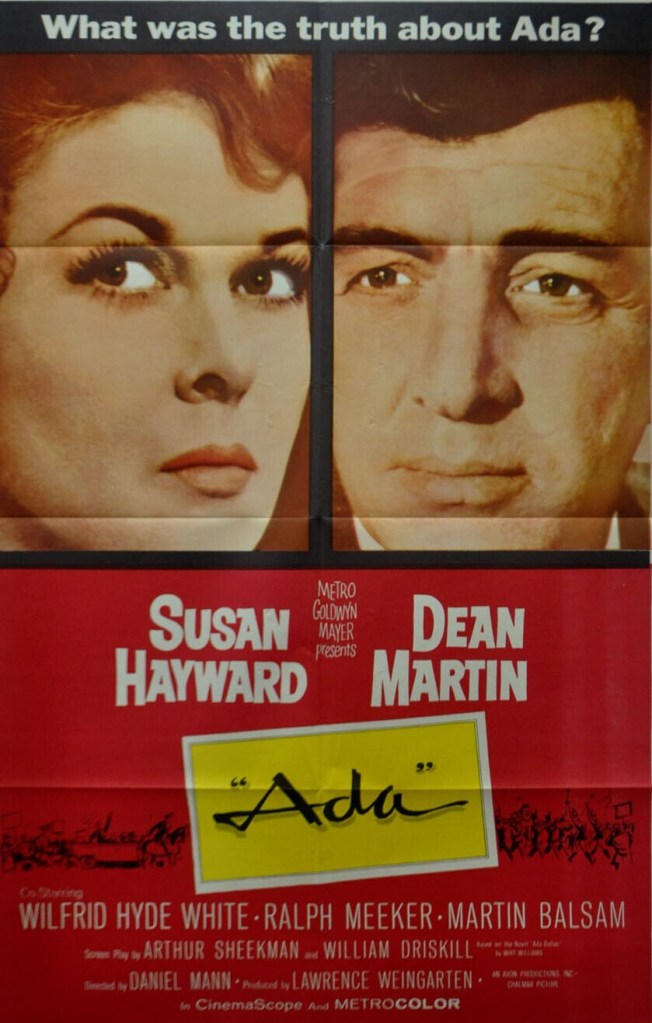

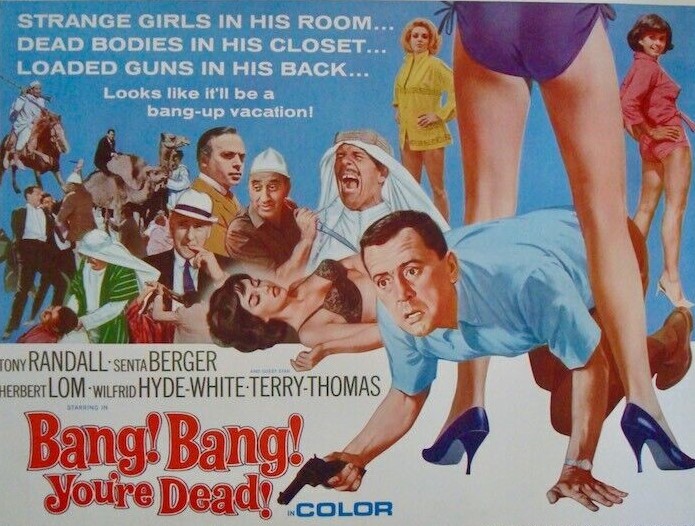

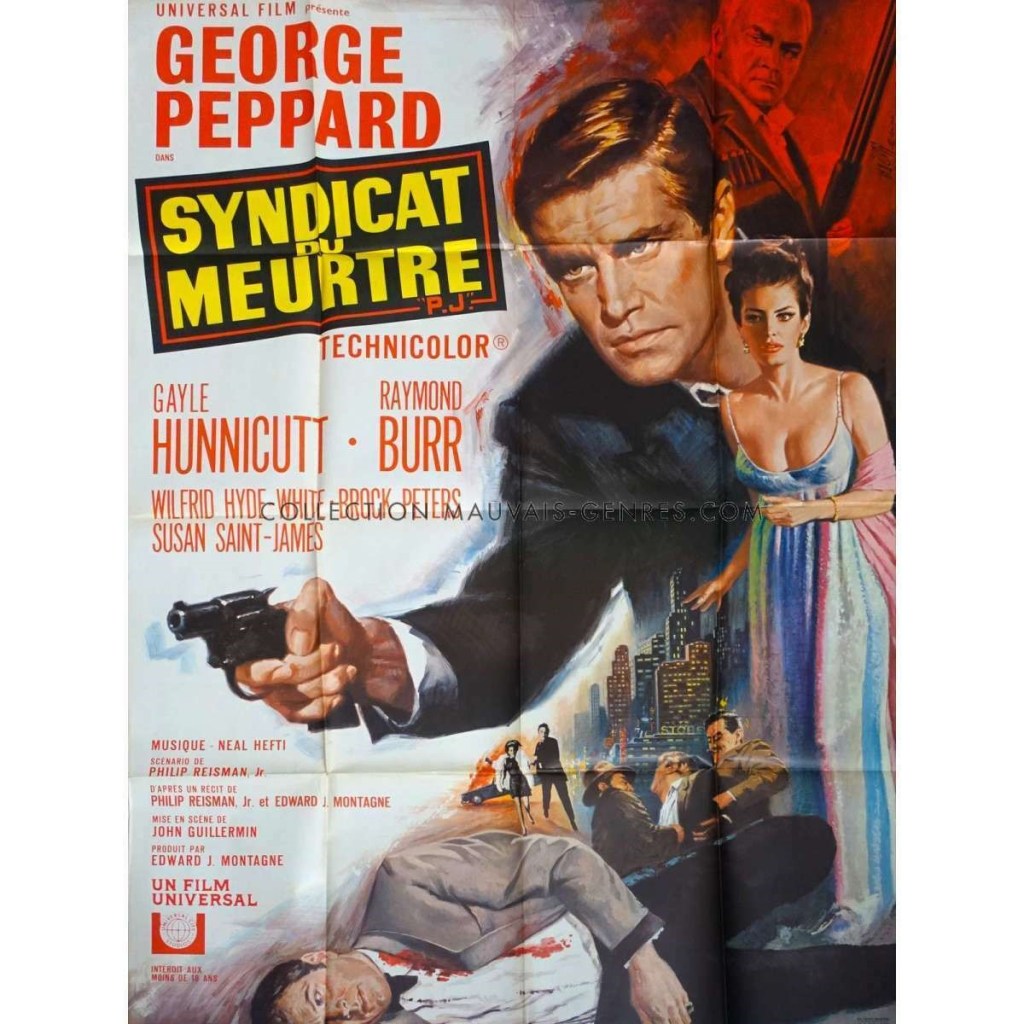

Wilfrid Hyde-White (P.J. / New Face in Hell, 1967), another who generally traded on his charm (in a supporting category of course), is also in the disguise business, so he steals a few scenes, too. James Robertson Justice (Father Came Too) would have stolen the picture from under the noses of Baxter and Phillips had he been given more scenes.

Directed by Ken Annakin (Battle of the Bulge, 1965) from a screenplay by Jack Davies and Henry Blyth (Father Came Too).

I might have preferred Phillips in “ding dong” persona, but this works out okay, especially in the scenes set in the criminal reform school.

Ding dong-ish.