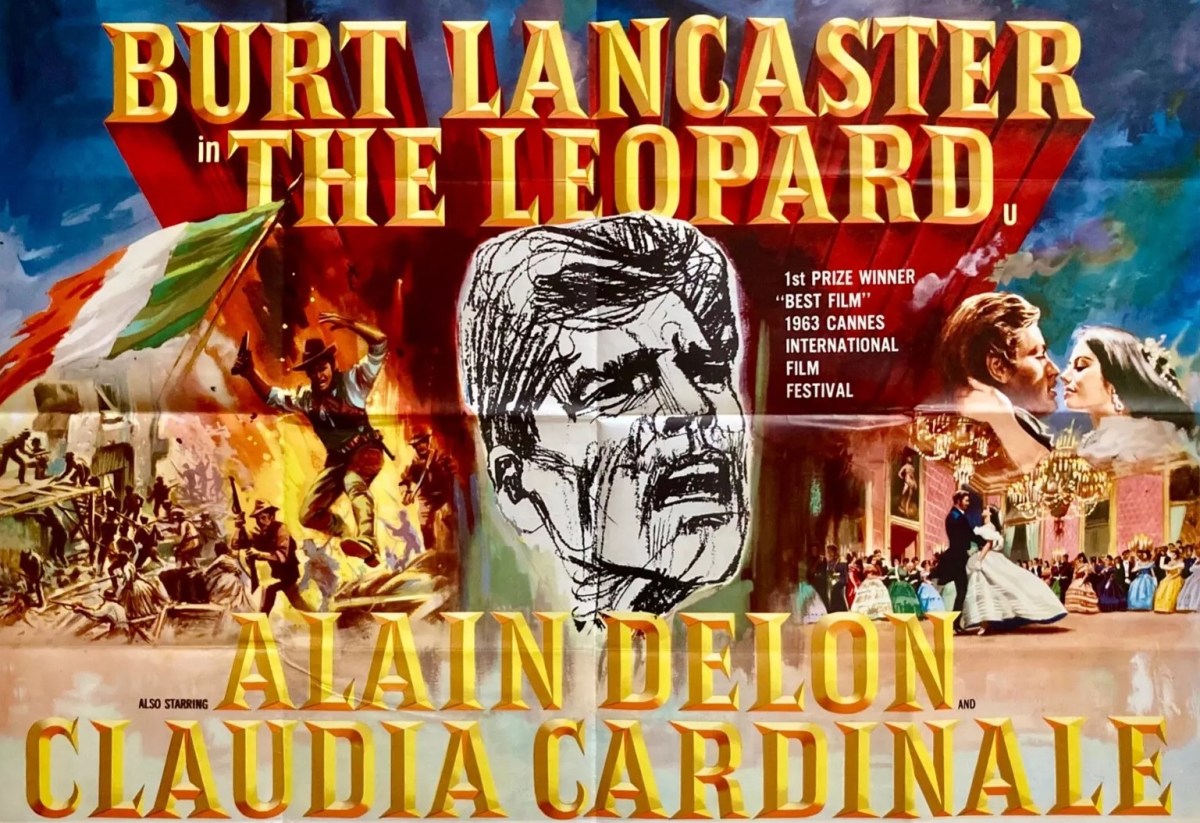

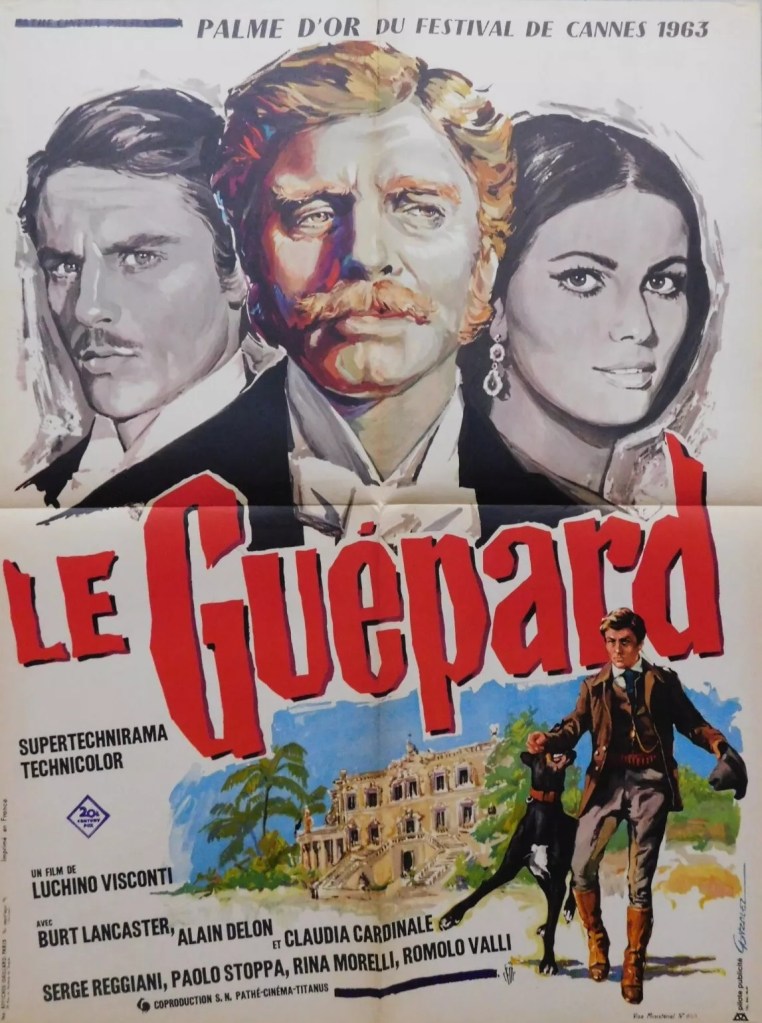

Masterpiece. No other word for the way director Luchino Visconti commands his material with fluid camera and three terrific performances (four, if you count the wily priest). An epic in the old-fashioned sense, combining intelligence, action and romance, though all three underlaid by national or domestic politics. And if you’re going to show crumbling authority you can’t get a better conduit than Burt Lancaster (check out The Swimmer, 1969, for another version of this), physical prowess still to the fore but something missing in the eyes. And all this on sumptuous widescreen.

Only a director of Visconti’s caliber can set the entire tone of the film through what doesn’t happen. We open with a religious service, not a full-scale Mass but recitations of the Rosary, for which the family is gathered in the massive villa of Prince Don Fabrizio Salina (Burt Lancaster). There is an almighty disturbance outside. But nobody dare leave or even react, children silently chided for being distracted, because all eyes are on the Prince and he has not batted an eyelid, worship more important than domestic matters.

Turns out there’s a dead soldier in the garden, indication of trouble brewing. Italy has been beset with trouble brewing from time immemorial so the Prince isn’t particularly perturbed, even if the worst comes to the worst an accommodation is always reached between the wannabes and the wealthy ruling elite.

There’s a fair bit of political sparring throughout but this is handled with such intelligence it’s involving rather than off-putting. Rebel Garibaldi is on the march, it’s the 1860s and revolution is on the way. But it’s not like the French Revolution with aristocrats executed in their thousands and when Garibaldi’s General (Guiliano Gemma) comes calling he addresses the Prince as “Excellency.”

The Prince is a bit of a hypocrite, not as devout as he’d like everyone to believe. He’s got a mistress stashed away for one thing and for another he blames his wife for the need to satisfy his urges elsewhere, complaining that she’s “the sinner” and that despite him fathering seven children with her he’s never seen her navel. Furthermore, the person he makes this argument to is the priest Fr Pirrone (Romolo Valli), who, knowing which side his bread is buttered on, doesn’t offer much of a challenge.

If you’re not going down the more perilous route of taking up arms, advancement in this society is still best achieved through marriage and the Prince’s ambitious nephew Don Tanacredi (Alain Delon), more politically astute, does this through marriage to Angelica (Claudia Cardinale), daughter of Don Calogeo Sedara (Paolo Stoppa).

Brutality and elegance sit side by side. You’re not going to forget the mob of women hunting down and hanging a Government police spy nor, equally, the astonishing ball that virtually concludes proceedings, showing that, whatever changes in society take place, those with money and privilege will still hold their own. But that’s only if they do a little bit of bending the knee to the new powers-that-be, something that Tancredi, by now a rebel hero wounded in battle, is more than happy to do, since that procures him even further advancement, but a step too far for the Prince, who at the end retreats into his study, as if this will provide sanctuary from the impending future.

Don’t expect battle on the scale of Lawrence of Arabia (1962), this action is a more scrappy affair, undisciplined red-shirted hordes sweeping through a town and eventually overwhelming cavalry and ranks of infantry.

But if you’re aiming to hold an audience for three hours, a decent script, romantic entanglement and camerawork isn’t enough. You need the actors to step up. Luckily, they do, in spades. Burt Lancaster is easily the pick, towering head and shoulders, and not just in physicality, above the rest, a man who sees his absolute authority draining away in front of his eyes. Alain Delon (Once a Thief, 1965) comes pretty close, though, not afraid to challenge his uncle’s beliefs nor point out his hypocrisy, and adept at picking his way through the new emerging society, his potential ascension to newfound power demonstrated by wearing a war wound bandage wrapped piratically around one eye, as though keeping a foot in both camps. Though American audiences never quite warmed to Delon, he was catnip for the arthouse brigade, courtesy of being anointed by Visconti and Antonioni in, respectively, Rocco and His Brothers (1960) and L’Eclisse (1962).

Far more than U.S. cinemagoers could imagine, Claudia Cardinale (The Professionals, 1966) also easily straddled commercial and arthouse – Rocco and His Brothers, Fellini’s 8½ (1963) – and on her luminous performance here you can see why. You might also spot future Italian stars Terence Hill (My Name Is Nobody, 1970) and Giuliano Gemma (Day of Anger, 1967). Adapted from the bestseller by Giuseppe Tomasi de Lampedusa by the director and his Rocco and his Brothers team of future director Pasquale Festa Campanile (The Libertine, 1968), Suso Cecchi D’Amico, Enrico Medioli and Massimo Franciosa.

I can’t quite get my head round the audacity of Netflix in attempting a mini-series remake. I’m assuming they’ve had the sense to buy up the rights to the Visconti to prevent anyone comparing the two.

One of the decade’s greatest cinematic achievements.