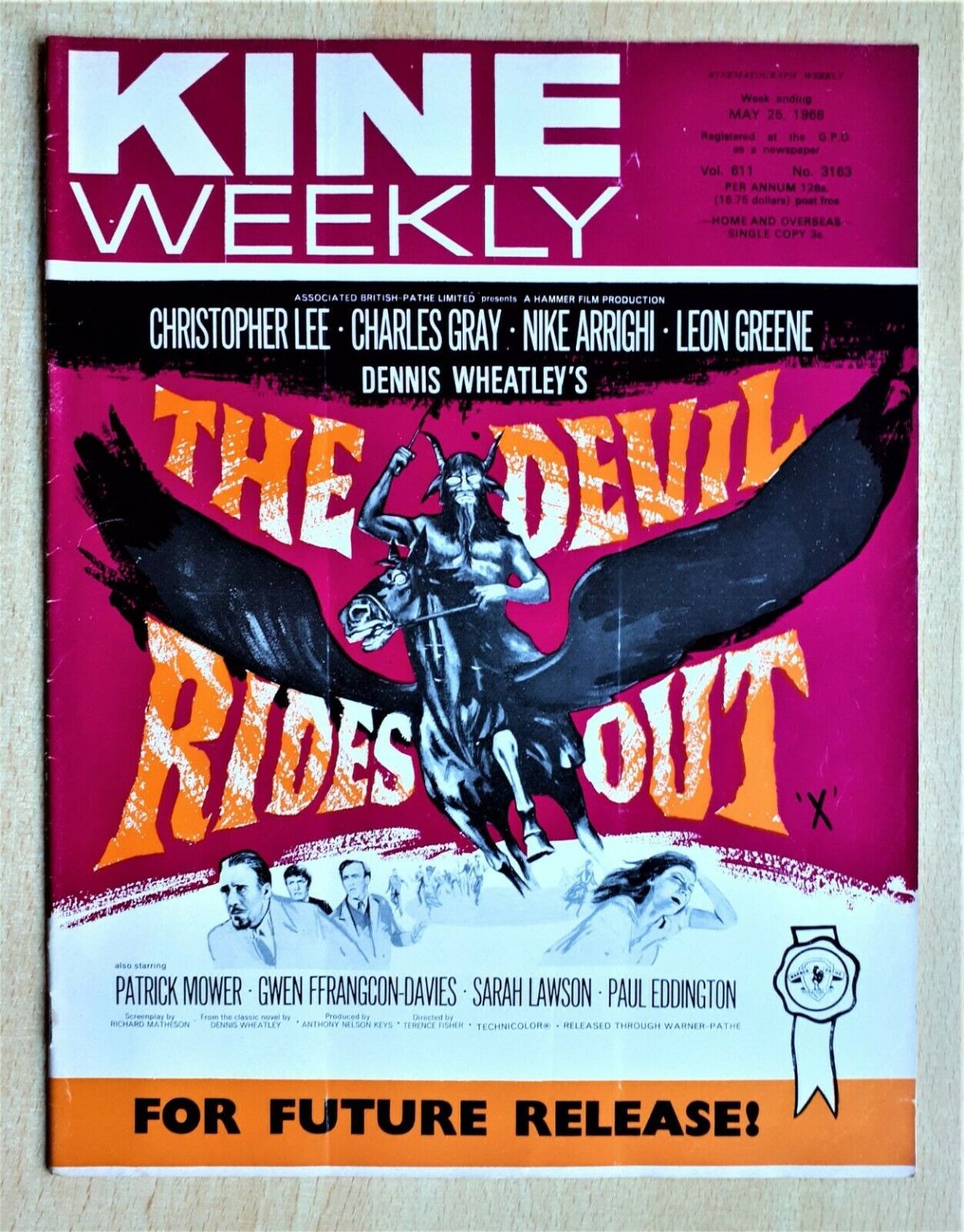

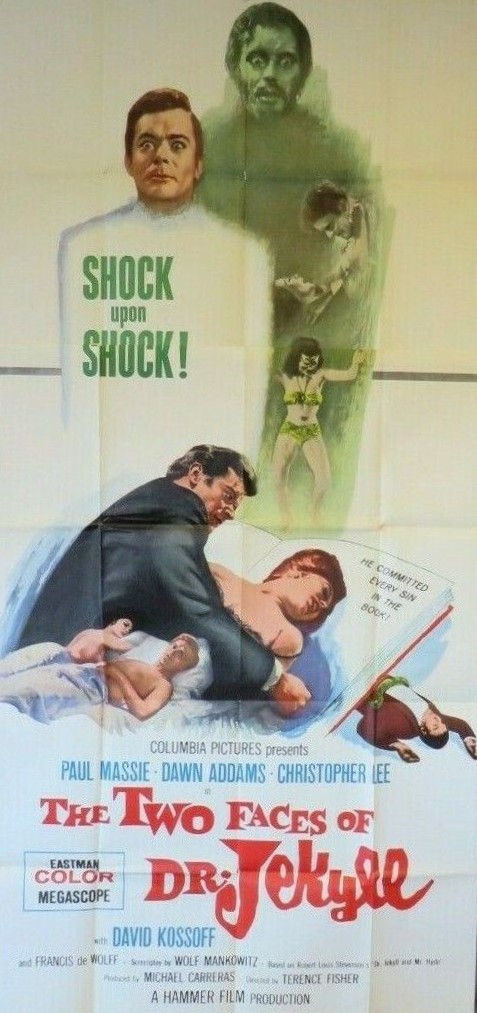

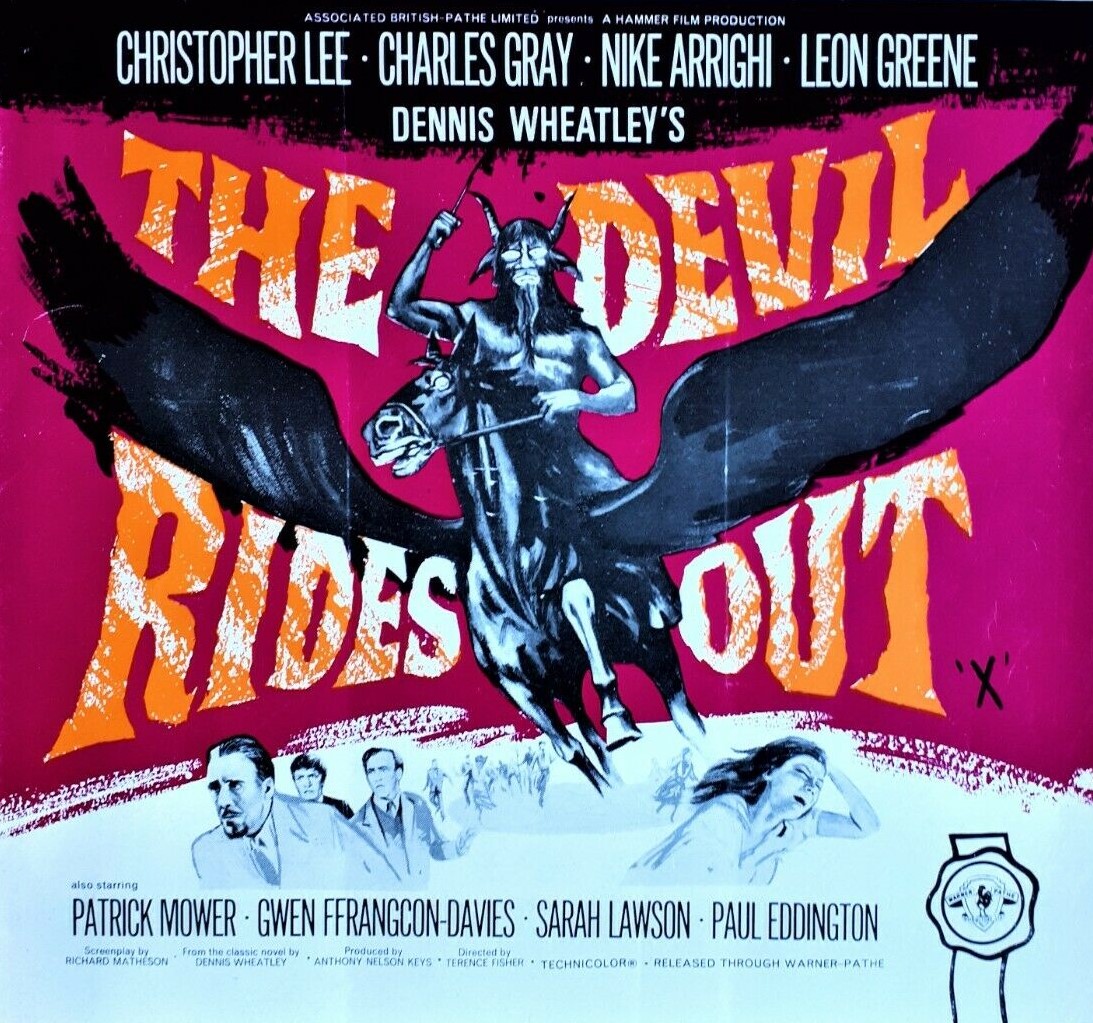

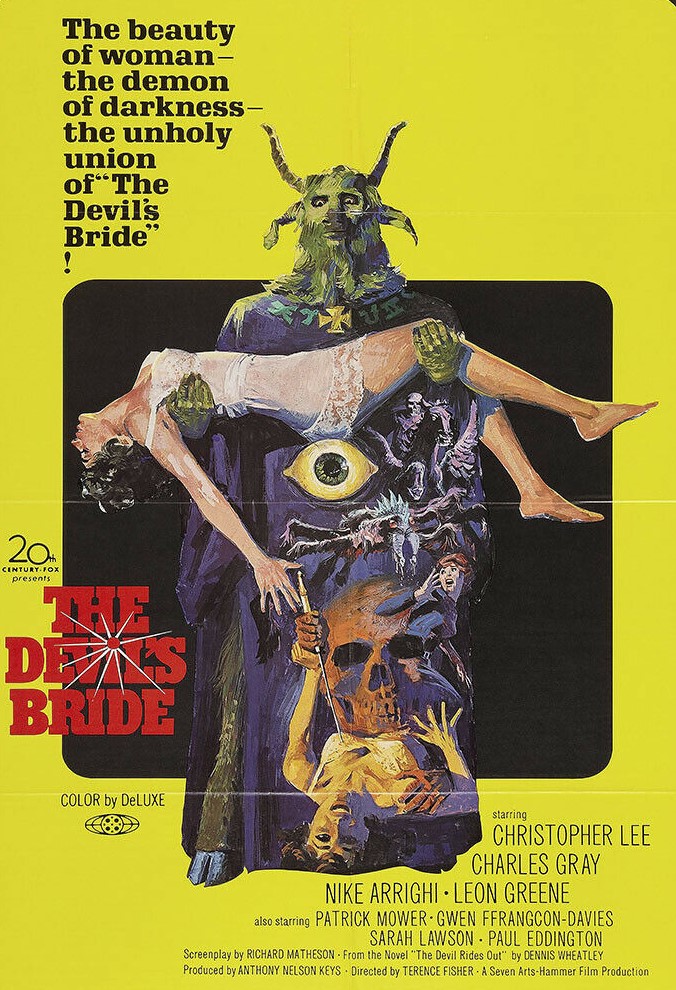

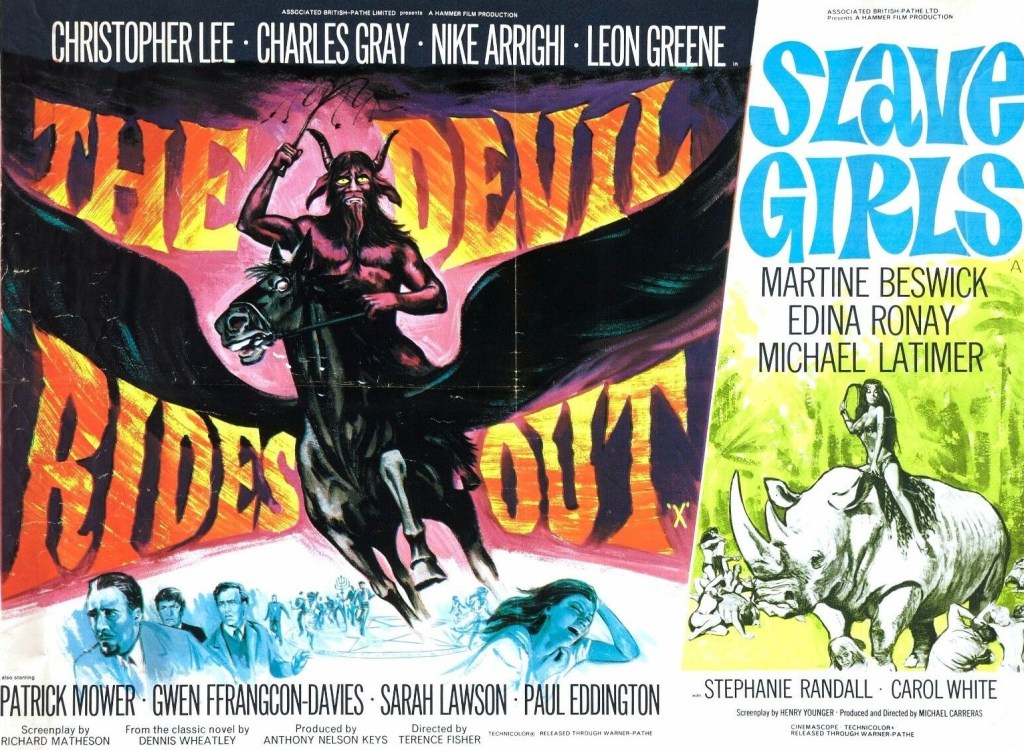

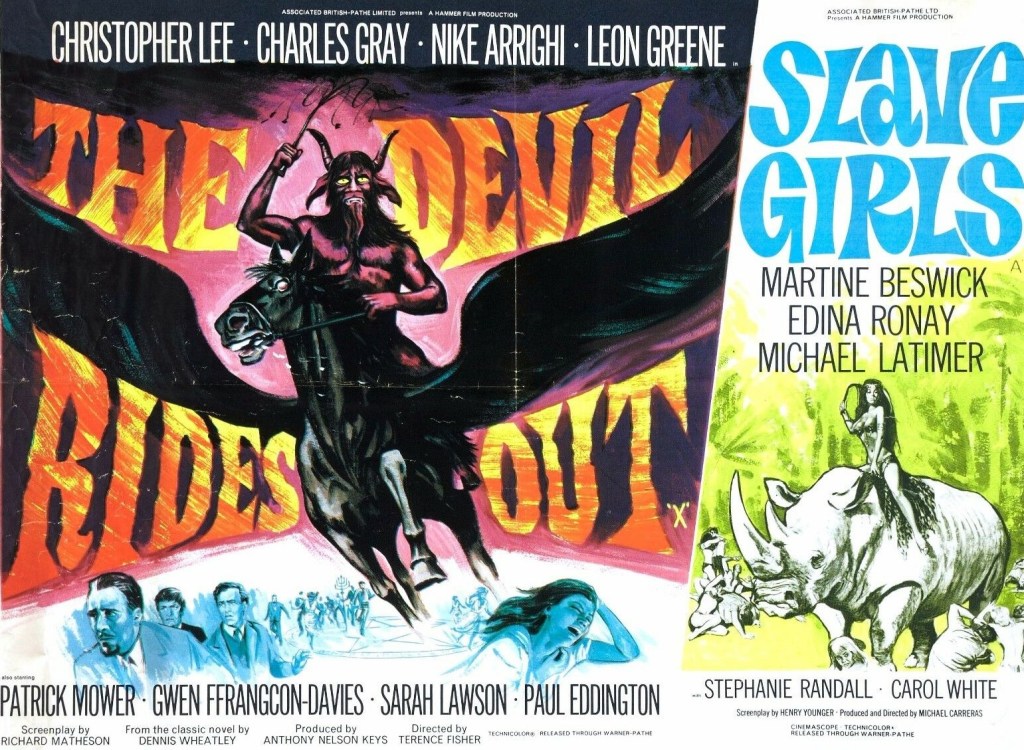

Strong contender for Hammer’s film of the decade, a tight adaptation of Dennis Wheatley’s black magic classic with some brilliant set pieces as Nicholas de Richleau (Christopher Lee) battles to prevent his friend Simon (Patrick Mower) falling into the hands of satanist Mocata (Charles Gray).

Initially constructed like a thriller with Simon rescued, then kidnapped, then rescued again, plus a car chase, it then turns into a siege as Richleau and friends, huddled inside a pentagram, attempt to withstand the forces of evil. Sensibly, the script eschews too much mumbo-jumbo – although modern audiences accustomed to arcane exposition through MCU should find no problem accommodating ideas like the Clavicle of Solomon, Talisman of Set and Ipsissimus – in favour of confrontation.

Unlike most demonic pictures, de Richleau has an array of mystical weaponry and a fund of knowledge to defend his charges so the storyline develops along more interesting lines than the usual notion of innocents drawn into a dark world. In some senses Mocata is a template for the Marvel super-villains with powers beyond human understanding and the same contempt for his victims. And surely this is where Marvel’s creative backroom alighted when it wanted to turn back time. Though with different aims, De Richleau and Mocata are cut from the same cloth, belonging to a world where rites and incantations hold sway.

While special effects play their part from giant menacing tarantulas and the Angel of Death, the most effective scenes rely on a lot less – Simon strangled by a crucifix, Mocata hypnotizing a woman, a bound girl struggling against possession. Had the film been made a few years later, when Hammer with The Vampire Lovers (1970) and Lust for a Vampire (1971) increased the nudity quotient, and after The Exorcist (1973) had led the way in big bucks special effects, the black mass sequence would have been considerably improved.

The main flaw is the need to stick with the author’s quartet of “modern musketeers” which means the story stretches too far in the wrong directions often at the cost of minimizing the input of de Richleau. In the Wheatley original, the four men are all intrepid, but in the film only two – de Richleau and American aviator Rex van Ryn (Leon Greene) – share those characteristics. At critical points in the narrative, de Richleau just disappears, off to complete his studies into black magic. Where The Exorcist, for example, found in scholarship a cinematic correlative, this does not try.

Christopher Lee (She, 1965), pomp reined in, is outstanding as de Richleau, exuding wisdom while fearful of the consequences of dabbling in black magic, both commanding and chilling. Charles Gray (Masquerade, 1965) is in his element, the calm eloquent charming menace he brings to the role providing him with a template for future villains. The three other “musketeers” are less effective, Patrick Mower in his movie debut does not quite deliver while Leon Greene (A Challenge for Robin Hood, 1967) and Paul Eddington (BBC television’s Yes, Minister 1980-1984) are miscast. Nike Arrighi, also making her debut as love interest Tanith, is an unusual Hammer damsel-in-distress.

Hammer stalwart Terence Fisher (The Gorgon, 1964) creates a finely-nuanced production, incorporating the grand guignol and the psychological. Screenwriter Richard Matheson (The Raven, 1963) retains the Wheatley essence while keeping the plot moving. A few years later nudity was no longer be an issue and Hollywood injected big bucks in horror special effects, so with those constraints in mind the studio did a devilish good job.

BOOK INTO FILM

Dennis Wheatley was a prolific bestseller producing three or four titles a year, famous for a historical series set around Napoleonic times, another at the start of the Second World War and a third featuring the “four modern musketeers” that spanned a couple of decades. In addition, he had gained notoriety for books about black magic, which often involved series characters, as well as sundry tales like The Lost Continent. Although largely out of fashion these days, Wheatley set the tone for brisk thrillers, stories that took place over a short period of time and in which the heroes tumbled from one peril to another. In other words, he created the template for thriller writers like Alistair MacLean and Lee Child.

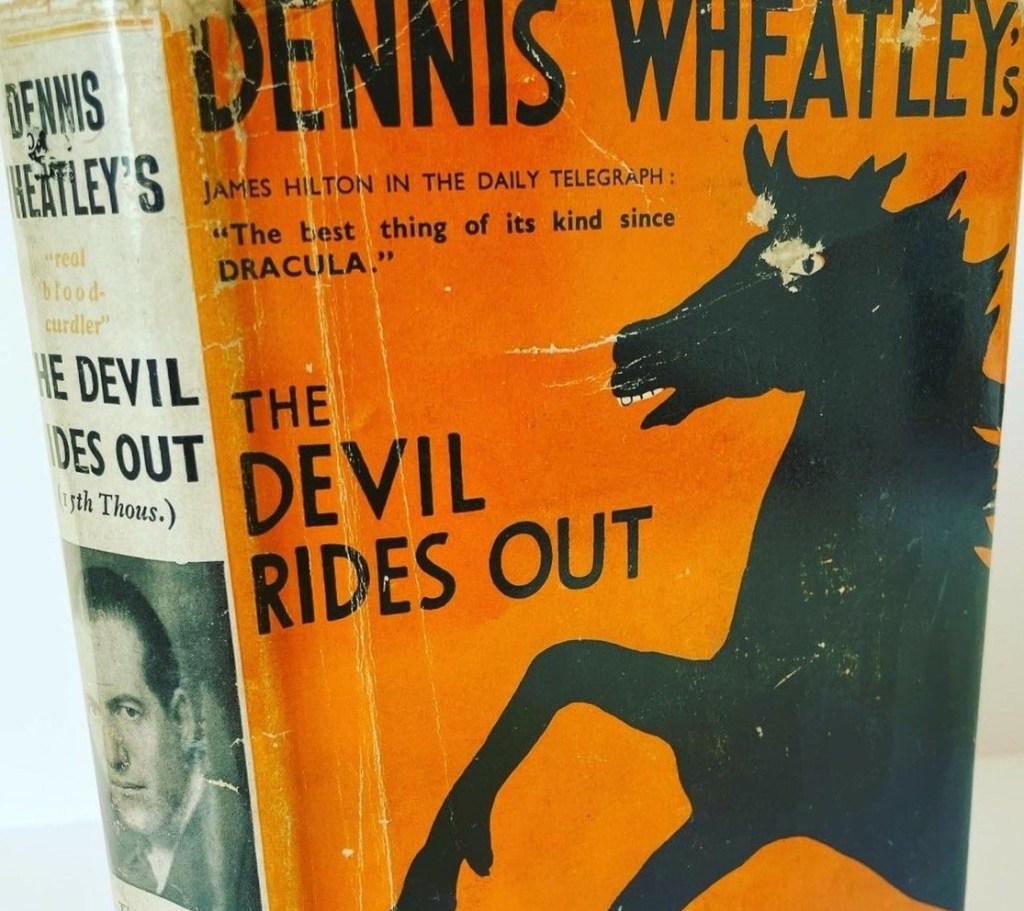

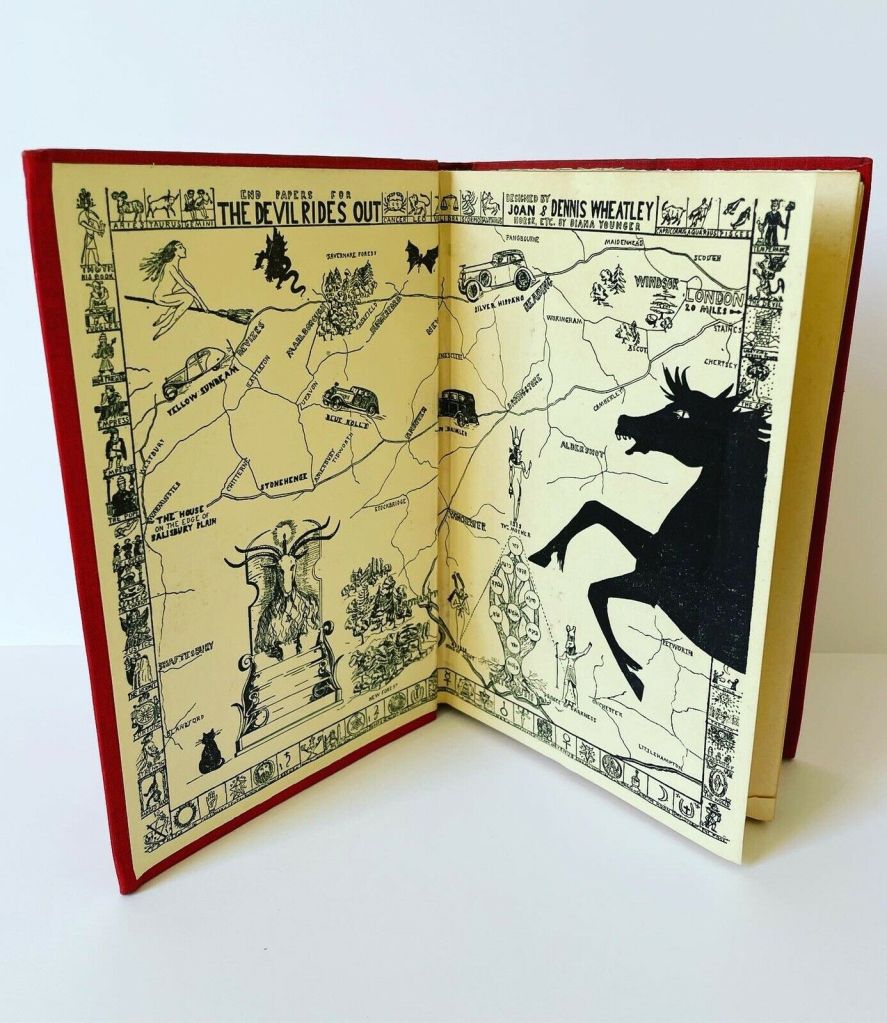

The Devil Rides Out, his fourth novel, published in 1934, featured the “musketeers” involved in his phenomenally successful debut The Forbidden Territory (1933), and introduced readers to his interest in the occult. Although of differing temperaments and backgrounds his quartet – the Russian-born Duke De Richleau (Christopher Lee in the film), American aviator Rex Van Ryn (Leon Greene) and wealthy Englishmen Richard Eaton (Paul Eddington) and Simon Aron (Patrick Mower) – are intrepid. And while screenwriter Richard Matheson stuck pretty much to the core of the Wheatley story, the film was hampered by the actors. The laid-back Paul Eddington hardly connects with the Wheatley characterization and Patrick Mower is too young for Aron.

As with the book, the story moves swiftly. Worried that Aron is dabbling in the black arts, De Richleau and Van Ryn go haring down to his country house where they meet black magic high priest Mocata (Charles Gray) and discover tools for satanic worship. And soon they are embroiled in a duel of wits against Mocata, climaxing in creating a pentagram as a means of warding off evil.

In order not to lose the audience by blinding them with mumbo-jumbo the script takes only the bare bones of the tale, bringing in the occult only when pivotal to the story, and that’s something of a shame. A modern audience, which has grown up on enormously complicated worlds such as those created for Game of Thrones and the MCU, would probably have welcomed a deeper insight into the occult. While out-and-out thrillers, Wheatley’s novels also contained copious historical information that he was able to dole out even when his heroes were in harm’s way. The Devil Rides Out is not a massive tome so it’s a measure of the author’s skill that he manages to include not just a condensed history of the occult but its inner workings. Every time in the film De Richleau goes off to the British Library for some vital information, his departure generally leaves a hole, since what he returns with does not always seem important enough to justify his absence.

But then the screenwriter was under far more pressure than a novelist. In some respects, this book like few others demonstrated the difference between writing for the screen and writing for a reader. With just 95 minutes at his disposal, Matheson had no time to spare while Wheatley had all the time in the world. Wheatley could happily leave the reader dangling with a hero in peril while dispatching De Richleau on a fact-finding mission, the action held up until his return. It’s interesting that Matheson chose to follow Wheatley’s characterization of De Richleau, who didn’t know everything but knew where to look. Matheson could easily have chosen to make De Richleau all-knowing and thus able to spout a ton of information without ever going off-screen.

But here’s where the book scores over the film. The reader would happily grant Wheatley his apparent self-indulgence because in the book what he imparted on his return, given the leeway to do so, was so fascinating. There are lengthy sections in the book which are history lessons where De Richleau gives readers the inside track on the satanic. In the opening section, once De Richleau and Van Ryn have rescued Aron, the author devotes a full seven pages to a brief introduction to the occult that leaves the reader more likely to want more of that than to find out how the story will evolve. He has hit on a magic formula that few authors ever approach. To have your background every bit as interesting as the main story is incredibly rare and it allowed Wheatley the opportunity to break off from the narrative to tell the reader more about the occult, which in turn, raised the stakes for the characters involved.

Effectively, there was too much material for a screenwriter to inflict upon an audience ignorant of the occult. Some decisions were clearly made to limit the need for lengthy exposition. But these often work against the film. For example, Mocata wants the Talisman of Set because it bestows unlimited power with which he can start a world war, but in order to accomplish that he needs to find people with the correct astrological births, namely Simon and Tanith. But this element is eliminated from the story, making Mocata’s motivation merely revenge. Matheson also removed much of the historical and political background, replaced the swastika as a religious symbol with the more acceptable Christian cross, and deleted references to Marie’s Russian background. Her daughter Fleur becomes Peggy. Matheson also treats some of the esoteric light-heartedly on the assumption that seriousness might be too off-putting.

Overall, the adaptation works, you can hardly argue with the movie’s stature as a Hammer classic, but the more you delve into the book the more you wish there had been a way for much of the material to find its way onscreen and to inform the picture in much the same way as the depth of history and character backstory added to Game of Thrones.