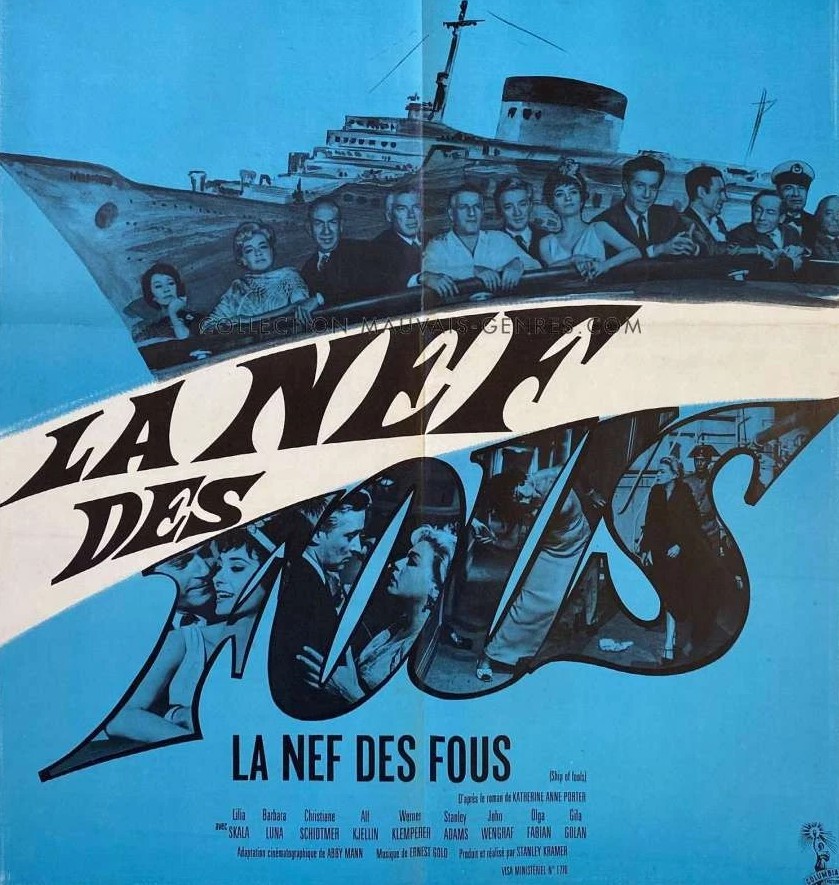

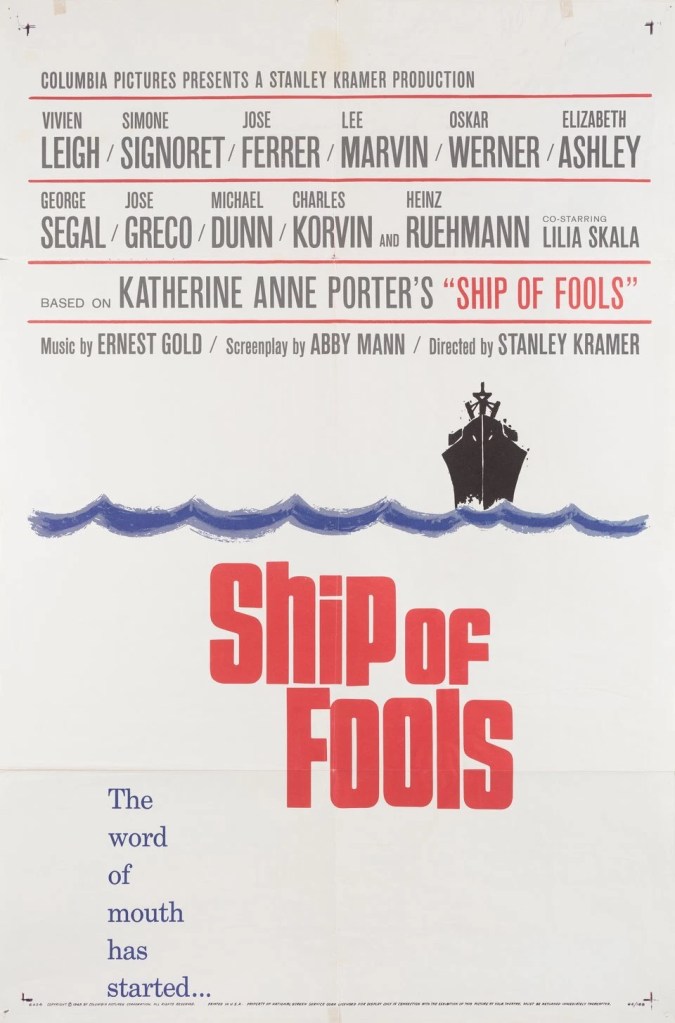

Stanley Kramer was on a roll, It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World – an outlier in his portfolio of serious pictures – his biggest-ever hit. Although United Artists, where the director had made his last four pictures, was initially in the frame for Katharine Anne Porter’s 1962 best seller Ship of Fools, the project ended up at Columbia which Kramer had last partnered on The Caine Mutiny in 1951. While the asking price was $450,000 plus a percentage, Kramer secured the rights for $375,000 although he chipped in $25,000 towards the book’s advertising campaign.

Kramer envisioned a character-driven film that would make up for the lack of action. He shifted the timescale to 1933 from 1931 to bring greater overtones of the Hitler threat. “Although we never mention him in the picture,” said Kramer, “his ascendancy is an ever-present factor.” Since there were no seagoing liners available to take over, the movie was shot entirely on the soundstage. “We filmed a ship’s ocean voyage without a ship and without an ocean.” He ransacked old footage for establishing shots of the ship, usually seen in the distance. Decks, staterooms and dining areas were constructed in the studio.

The kind of muted color he would have preferred was not available and since “the theme was just too foreboding for full color” he decided to film in black and white. Shooting in black and white wasn’t yet redundant. Of 27 features going in front of the cameras in 1964, six (including The Disorderly Orderly and Hush, Hush, Sweet Charlotte) were made in monochrome – down from ten out of 24 the year before.

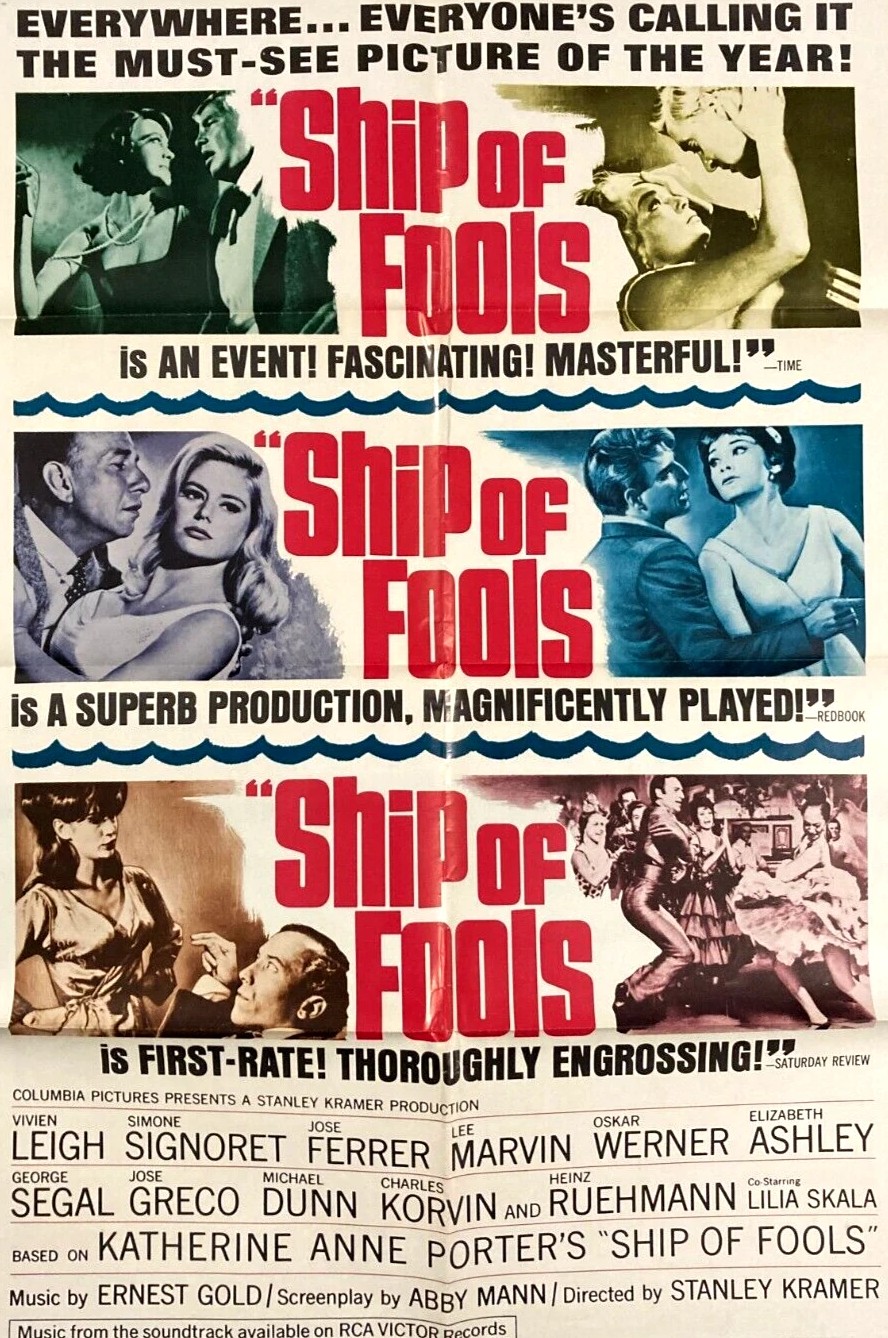

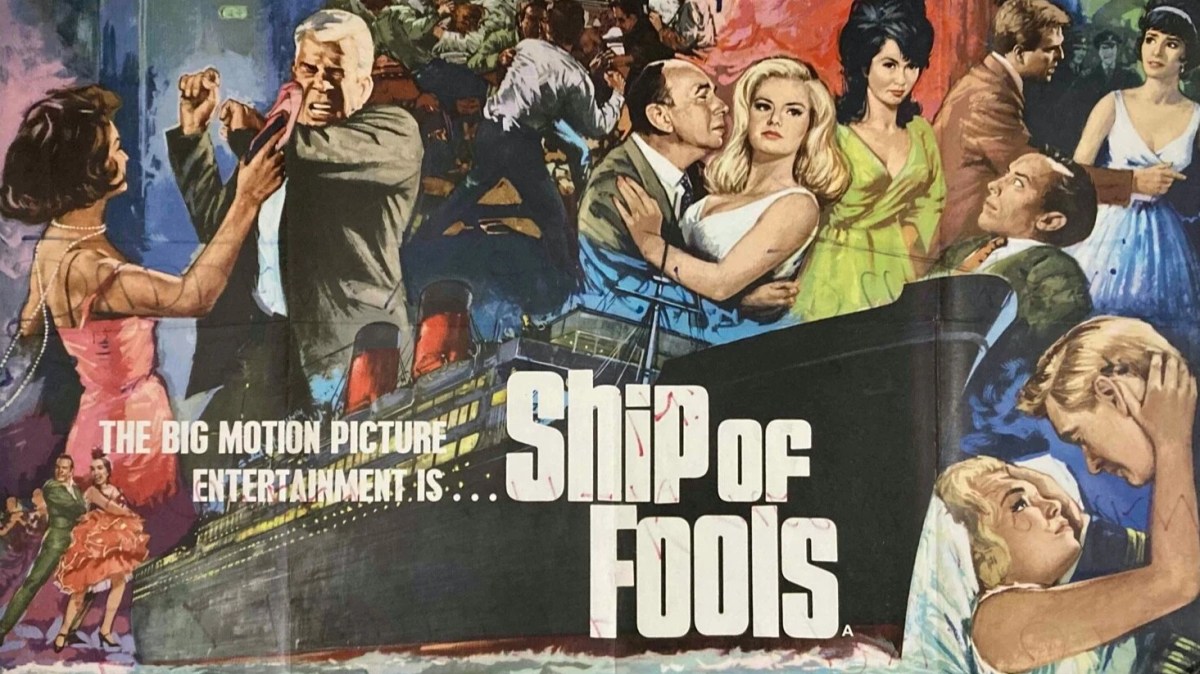

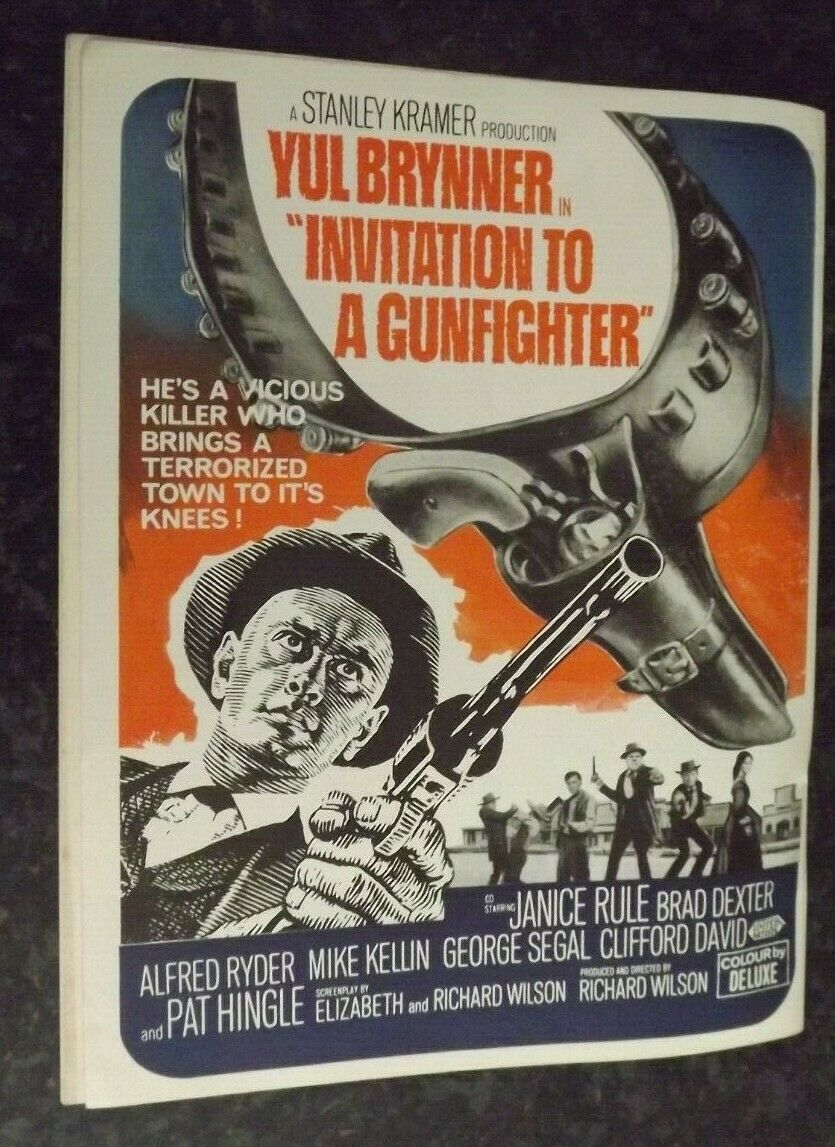

A thoughtful epic was always going to have trouble finding stars especially as current wisdom was that the industry only had at its disposal 22 genuine box office stars “thinly sprinkled” through the 43 pictures currently in production. While the movie’s marketeers boasted of an all-star cast, the reality was that while overall the actors had “combined heft” they were “minus any individual box office behemoth.”

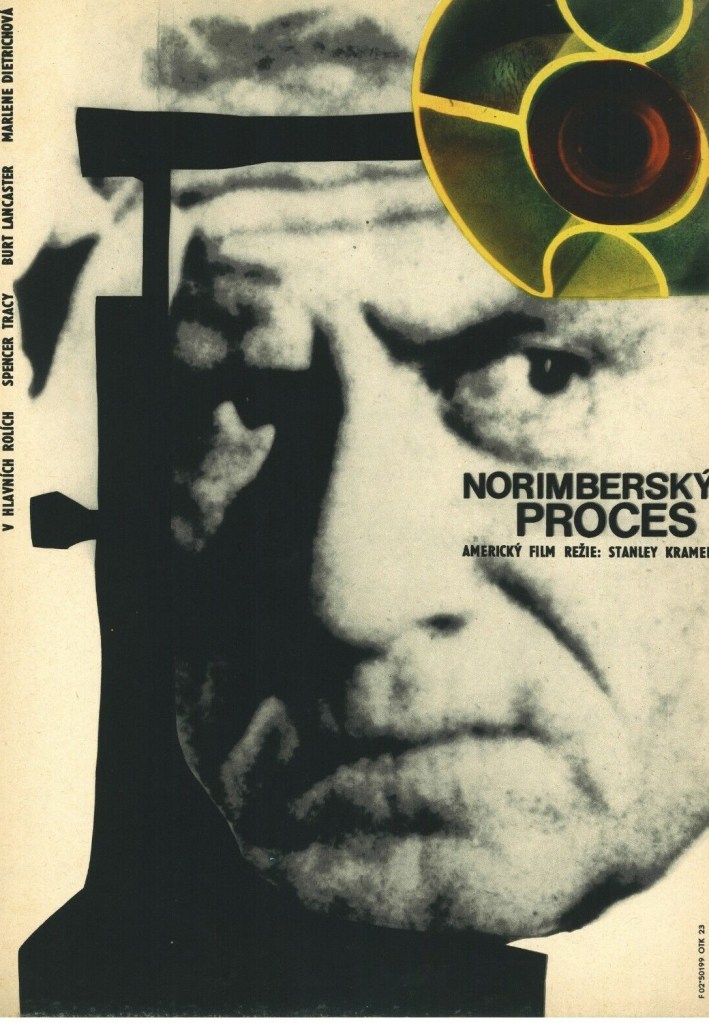

Spencer Tracy, whom Kramer initially envisioned for the role of the ship’s doctor and who had starred in the director’s last three pictures, would have added definite marquee allure, but he was unavailable due to illness. Greer Garson and Jane Fonda also fell by the wayside.

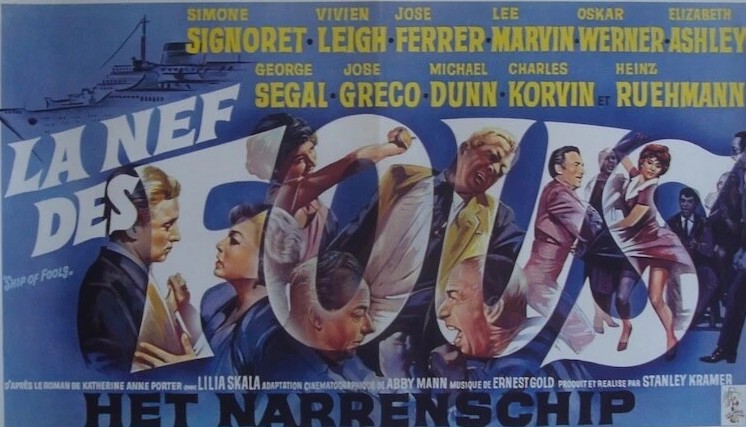

And unusually, Kramer insisted that many of those actors were not American. Vivien Leigh was born in India, Simone Signoret – who had just quit Zorba the Greek (1964) – was German and Oskar Werner Austrian. Jose Ferrer (who had won the Oscar in Kramer’s production of Cyrano de Bergerac, 1950) hailed from Puerto Rico, Jose Greco from Italy, Charles Korvin from Hungary, Lila Skalia from Austria and Alf Kjellin from Sweden. Signoret and Skala had Jewish ancestry.

His biggest casting coup was luring double Oscar-winner Vivien Leigh (The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone, 1961) out of retirement. But that was a double-edged sword. In real-life she led a tortured existence. Her marriage to Laurence Olivier was over and she had only appeared in two films since A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). She suffered from mental illness and tuberculosis. “Happiness or even contentment” eluded her and in that respect she was ideal for the role. “I’m sure she realized that, in the picture, she was playing something like her own life yet she never, by word of gesture, betrayed any such recognition.” She was another gamble, the reason her dance card was so empty down to directors despairing of getting a performance out of her.

Kramer flew to Germany to persuade Oskar Werner to take on the role intended for Spencer Tracy. At the time Werner, while familiar to European audiences and the American arthouse set through Jules and Jim (1962),was a relative unknown and a casting gamble. On set he proved obstinate. For one scene where he was instructed to enter camera right he did the opposite. When the direction was repeated, he stood his ground, insisting he preferred that view of his face. Despite the cost of reversing the set-up Kramer was forced to concede. Despite these trials, Kramer got along with Werner better than the actors. “They just couldn’t stand him.” Notwithstanding such difficulties Kramer later signed him for another film, but the actor died before shooting began.

James MacArthur (The Truth about Spring, 1964) was mooted for a role as was Sabine Sun (The Sicilian Clan, 1969). The most unlikely prospect was German comedian Heinz Ruhmann who was cast as Lowenthal. The Screen Actors Guild complained when Kramer hired five Spaniards instead of Americans for bit parts paying union scale of $350 a week, but their complaints were ignored.

Kramer admitted the ingénue roles played by George Segal (The Bridge at Remagen, 1968) and Elizabeth Ashley (The Third Day, 1965) were too much of a cliché. “As in most pictures,” observed Kramer, “older actors not only had more stature but they were also better armed by the writers. There was no way Segal and Ashley could compete with Werner and Signoret.”

The film cost $3.9 million. Filming began on June 22, 1964. It was initially a long shot for roadshow release but since Columbia was already committed to the more expensive Lord Jim and there were already 15 others lined up from other studios, Columbia nixed the two-a-day release in favour of continuous program.

Boosted by book sales – it was the number one hardback bestseller of 1962 and had sold millions in paperback – the movie carved out a more commercial niche than had been anticipated. Positive reviews helped. It opened to a “mighty” $88,000 in New York breaking records at the 1,003-seat Victoria and the 561-seat Sutton arthouse.

There was a “socko” $25,000 in Chicago, “giant” $23,000 in Philadelphia, “sock” $14,000 in Baltimore, “strong” $13,000 in St Louis, “lively” $12,000 in Detroit, “stout” 12,000 in San Francisco, “sturdy” $11,000 in Pittsburgh, and “slick” $10,000 in Columbus, Ohio. The only first run location where it toiled was Denver where it merited a merely “okay” opening of $8,000.

There was a sense of Columbia letting it run as long as possible in first run in the hope of garnering Oscars to boost its subsequent runs. But the studio was the beneficiary three times over from the Oscars – with Cat Ballou, Ship of Fools and William Wyler’s The Collector in contention for various awards.

The studio had the clever idea of pairing Ship of Fools in reissue with Cat Ballou, for which Marvin had won the Oscar, and although not the star of Ship of Fools the teaming suggested it was a Marvin double bill. In Los Angeles the double bill hoisted $135,000 from 21 houses followed by $121,000 from 28. But in Cleveland Ship of Fools went out first with The Collector and then Cat Ballou. A mix-and-match strategy also saw Ship of Fools double up with, variously, A Patch of Blue, Darling and The Pawnbroker.

The final tally was difficult to compute. In its 1965 end-of-year rankings Variety reckoned it had only pulled in $900,000 in rentals but it was good for $3.5 million in the longer term, a realistic target once you counted in the $1.3 million in rentals generated by the combination with Cat Ballou.

SOURCES: Stanley Kramer with Thomas F. Coffey, It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, A Life in Hollywood (Aurum Press, 1997) pp203-212; “New York Sound Track,” Variety, May 2, 1962, p4; “375G for Fools Novel,” Variety, May 2, 1962, p5; “Publisher’s Big Break,” Variety, May 23, 1962, p4; “Kramer to Produce Ship of Fools for Columbia,” Box Office, June 18, 1962, p9; “Abby Mann to Script Ship of Fools,” Box Office, November 1962, pSE4; “Top German Comic,” Variety, April 15, 1964, p23; “Simone Signoret Exits Zorba,” Variety, April 22, 1964, p11; “Control of Space,” Variety, May 6, 1964, p4; “Five Spaniards on Ship of Fools Irks SAG,” Variety, June 3, 1964, p5;“To Speed MacArthur for Ship of Fools,” Variety, June 10, 1964, p17; “27 Features Shoot in Color, Only Six in Monochrome,” Variety, August 5, 1964, p3; “Perennial Quiz,” Variety, September 2, 1964, p1; “15, Maybe 17, Pix for Roadshowing,” Variety, October 28, 1964, p22; “Too Many Roadshows,” Variety, August 2, 1965, p5. Box office figures, Variety September-November 1965, “Big Rental Pictures of 1965,” Variety, January5, 1966, p6.