Nobody told me this was a musical and a dire one at that, characters breaking into dirge-like tunes at any opportunity and throwing themselves about as if choreographed by Bob Fosse on speed. The kind of film where visual imagination is so limited that every now and then when a snake hoves into view, tongue tipping out, that we’re supposed to realize it’s an image from the Garden of Eden.

It’s such a mess that the director tries to rescue the narrative by imposing a dreadful voice-over commentary that tells us what the screen should have made abundantly clear. This device either robs sequences of any potency or avoids creating any scenes of note by relying on the voice-over to fill in the blanks.

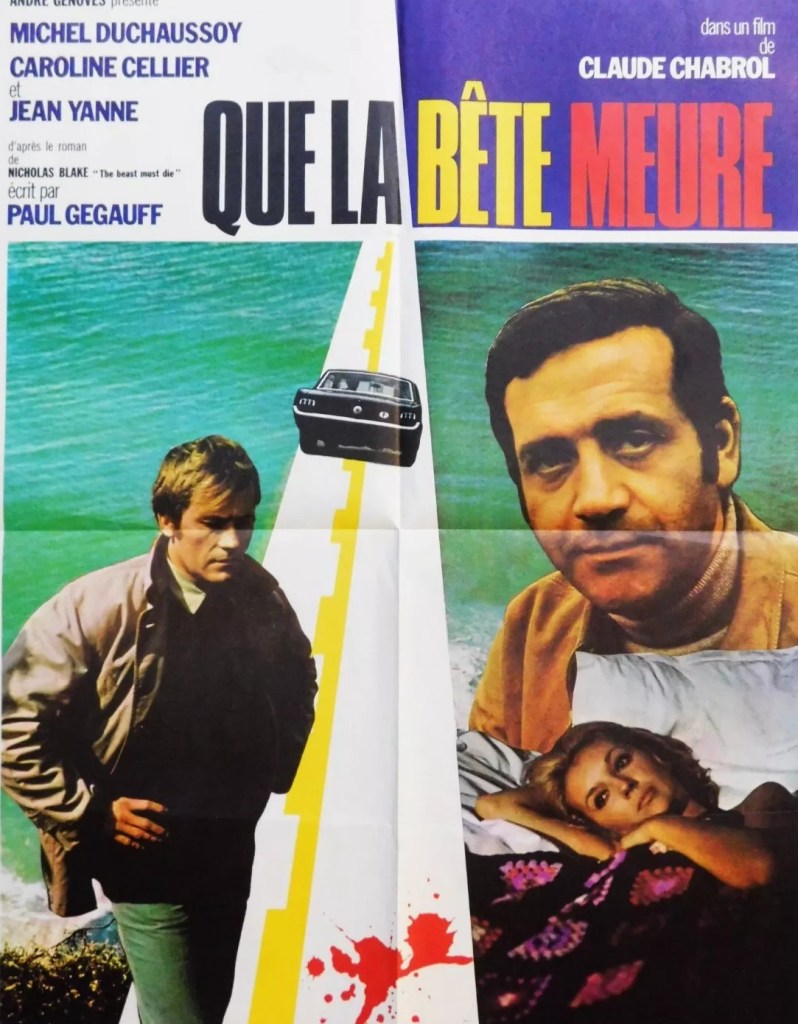

And that’s a shame because there is a good story here to tell. A feminist one for a start, a woman by her own merit achieving a position of considerable importance in eighteenth century Britain and America. If you only knew the term “Shaker” in terms of furniture, then this is the one to disabuse of that notion. However, that term seemed to be one of contempt, an offshoot of the Quakers, who believed a woman would lead the Second Coming, which espoused a religion where they were shaking all over as an essential part of their worship of God, in part related to confessing their sins, but in part, I would guess, because singing and dancing with abandon offered pure physical – not to say sexual – release.

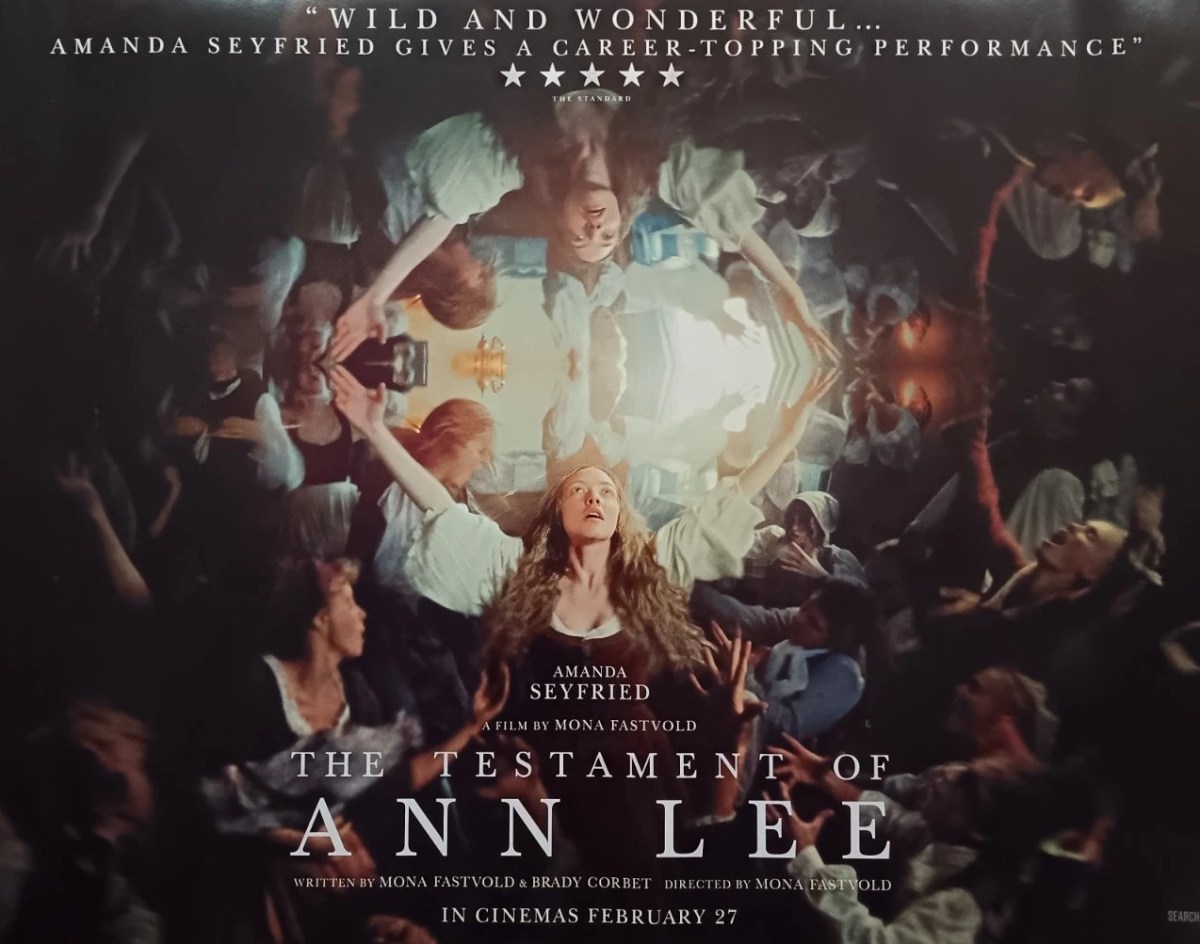

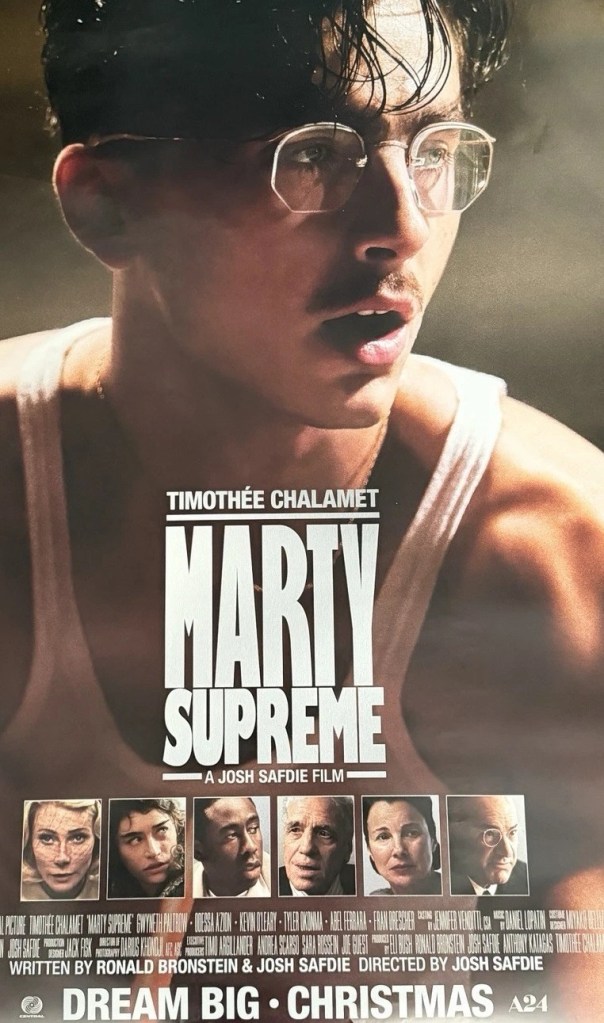

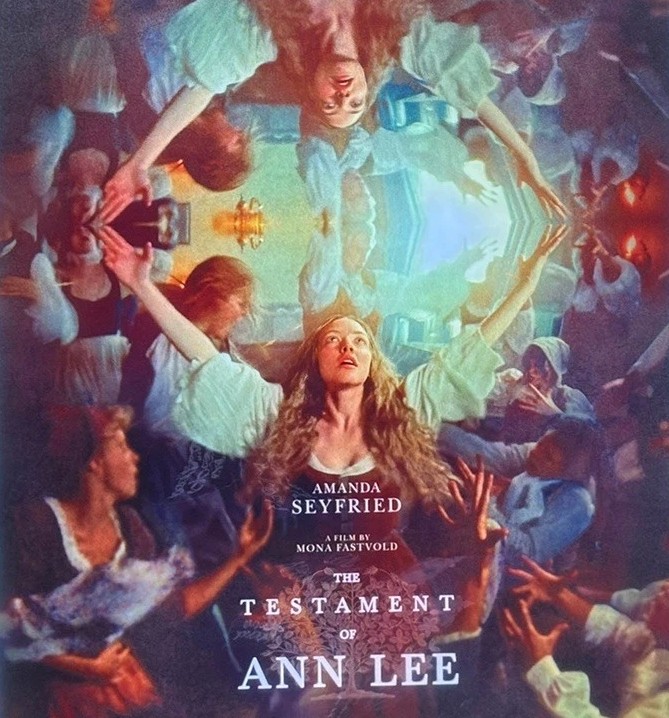

It was a particularly noisy religion. The stomping and yelping attracted so much attention that they were liable to be arrested for being too noisy. But there was a bright side to languishing in prison, at least for our heroine Ann Lee (Amanda Seyfried), who, on the brink of starvation, saw visions that elevated her to a position of leadership – the new Messiah – among her clique.

One of the tenets of the religion – no doubt caused by her being in a state of endless pregnancy with no progeny to show for it, all four offspring dead at birth or soon after – was celibacy. Fornication was strictly forbidden. While nobody gave mind to how that might prevent a new generation carrying on the religion, no doubt it contributed to its popularity amongst women who had to give in to their husband’s sexual demands even though continuous pregnancy wore them out.

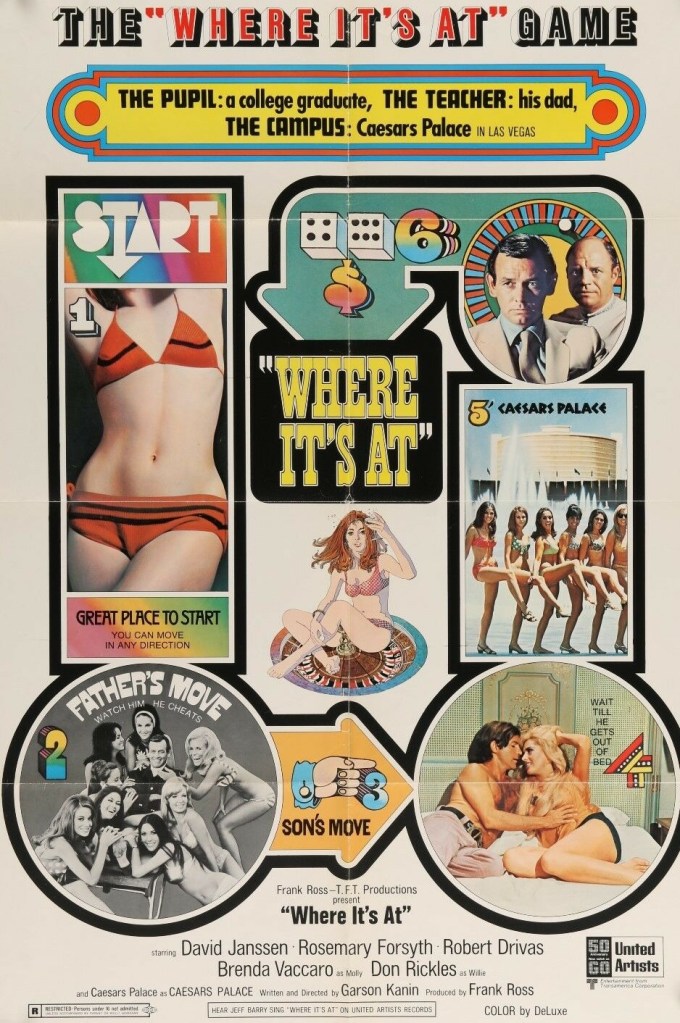

Never mind the pregnancies, Ann had a particularly good reason for wanting to stop having sex with her husband Abraham (Christopher Abbott). He was fond of pornography (yes, the printed stuff existed then and was even illustrated so it appears), and of giving her a good whipping as a prelude to sex and he was also bisexual.

They take their singing and dancing to America. The lack of sex leaves Abraham to abandon his wife, which is just as well because she’s too busy setting up Shaker communities to be involved in any intimacy with a perverted male.

The singing and dancing aspect doesn’t go down so well in the New World, it being too close to witchcraft for some, and accusations of witchcraft being the easiest way for the male hierarchy to keep women in their place. For every believer there are a ton of angry disbelievers who don’t want anyone shaking all over.

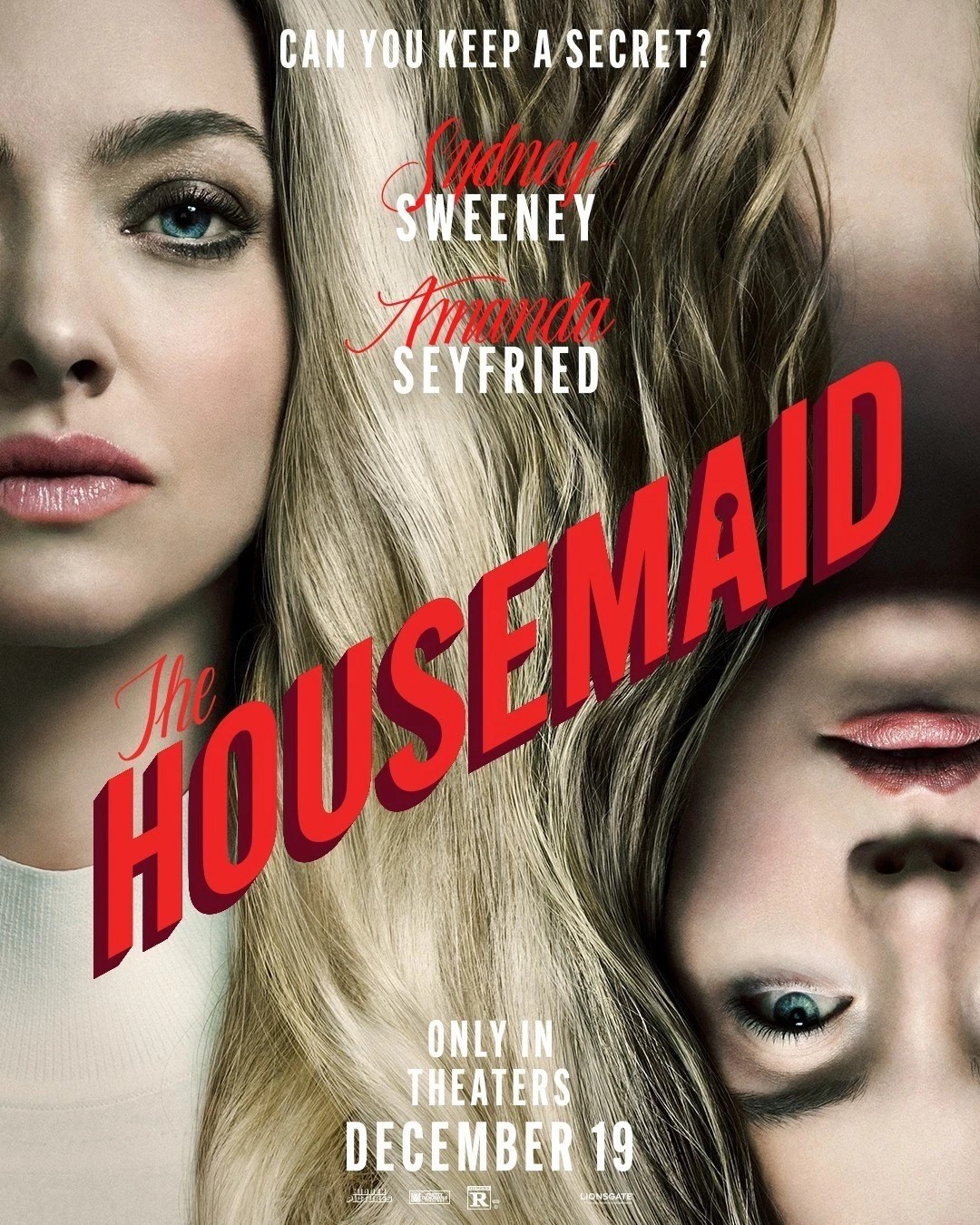

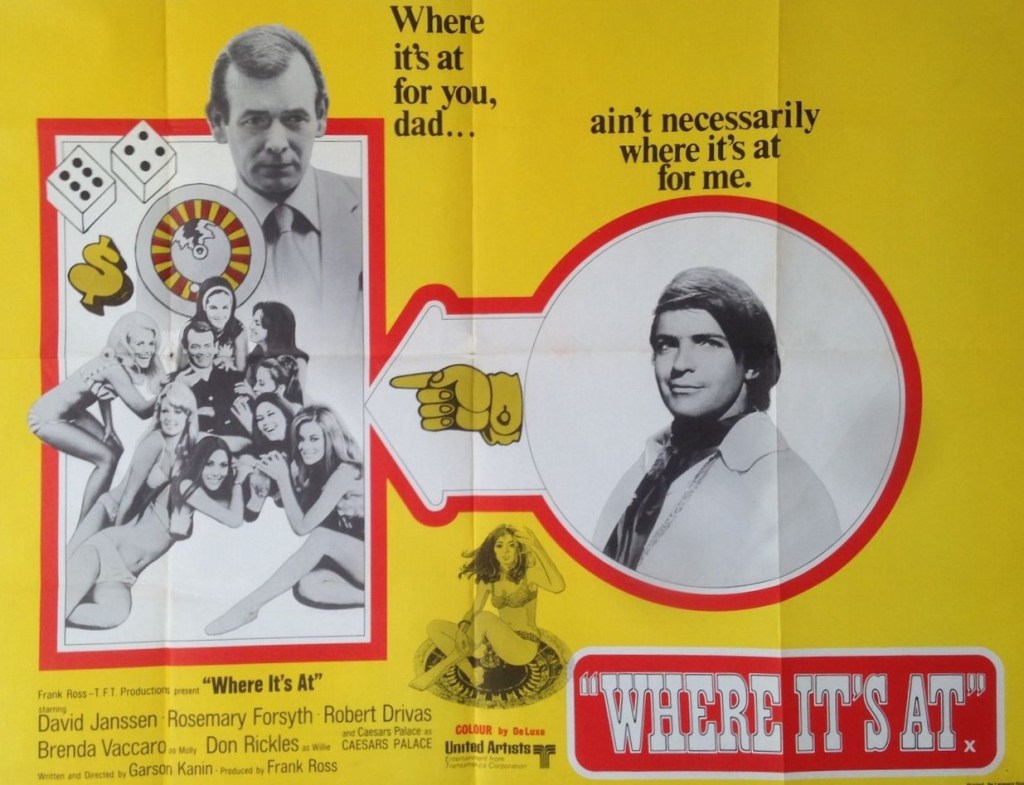

I saw this as part of my usual Monday triple bill that had got off to a very good start with the interesting, though far from superlative, Elvis Presley in Concert, followed by a more than tolerable Scream 7 with Neve Campbell (returning now that the producers had acceded to her salary demands) introducing her daughter to the delights of being chased by Ghostface. I was looking forward to having enjoyed a very decent day out at the cinema. Alas, the final picture torpedoed that notion.

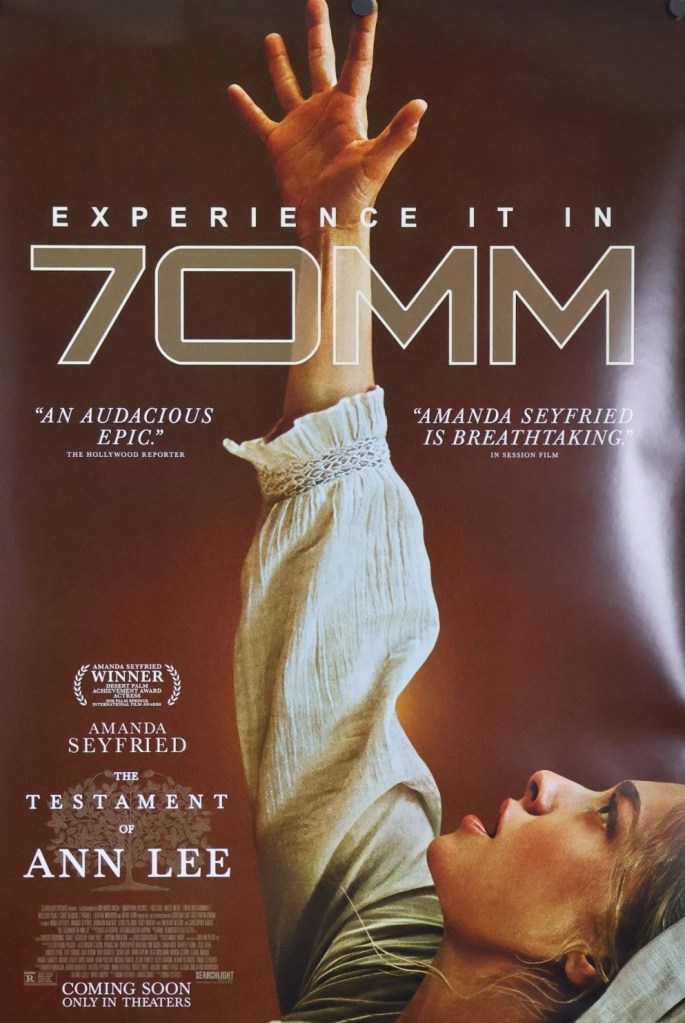

I should have known better than to avoid films that were touted as more than worthwhile on the back of critical acclamation and an Oscar nomination for the lead. If Oscar nominations were handed out for people debasing themselves or not using make up such as Demi Moore (The Substance, 2025), then Clint Eastwood should have been more in line for similar recognition given the number of times he was whipped or beaten up.

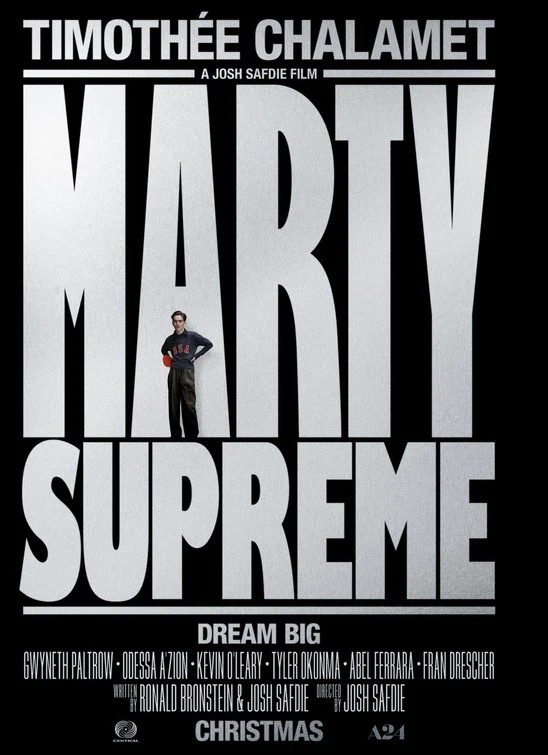

Certainly Amanda Seyfried (The Housemaid, 2025) goes through the hoops here but, frankly, the movie is such a shambles and the voice-over kills off much of the narrative structure that she’s wasted.

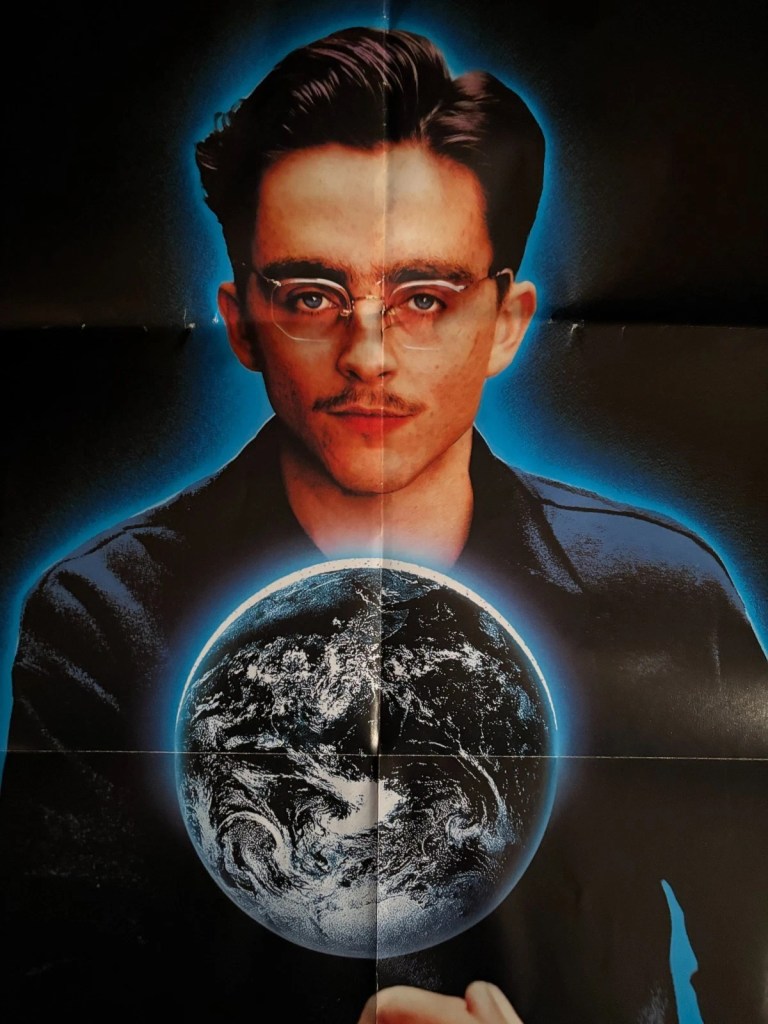

Another “visionary” director in the form of Mona Fastvold (The World to Come, 2020) who with husband Brady Corbett (The Brutalist, 2024) wrote the screenplay and who, having been given too much rope by indulgent financiers, proceeds to hand herself.

It might have worked minus the singing and eternal dancing and with the voice-over stripped out and the picture trimmed by a good 20 minutes. Who knows, we might get a director’s cut where the director sees the error of her ways and delivers a more sensible version.

The person sitting next to me in the multiplex gave up after a mere 20 minutes. I wish I had followed suit.

Just awful.