Hugely enjoyable caper driven by the sleekest and leanest of screenplays from Hollywood screenwriting royalty Ron Bass (Rain Man, 1989) and William Broyles (Apollo 13, 1995). We learn virtually nothing, not even surnames, about principals Mac (Sean Connery) and Gin (Catherine Zeta-Jones) beyond that they are top-notch thieves. So the narrative isn’t weighted down or driven into the barren wastes of left field by alcoholism or any other addiction, and nobody’s lamenting loss, and career girl Gin has little difficulty knocking back the clumsy romantic attempts of nerdy boss Cruz (Will Patton).

There’s a host of tight twists, not least of which is a reversal of The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) in that Gin, while purportedly hunting down the virtually anonymous Mac for a string of high-tech robberies on behalf of an insurance company, is in fact trying to pin the blame on him for thefts she undertook herself. The climax involves three clever twists in quick succession.

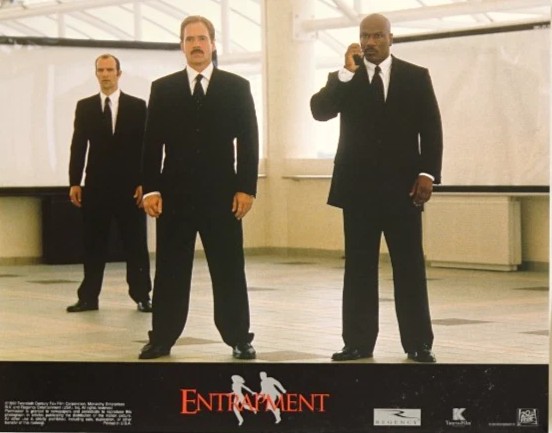

In keeping with the overall leanness, the narrative concentrates on a succession of clever and increasingly more audacious robberies, culminating in a heist on the eve of the Millenium of a cool eight billion bucks from all the banks in the world. As they join forces, Mac becomes the mentor, although Gin has moments of exerting control in the working relationship. Capable of causing trouble in the background are the agitated Cruz, threatening to work out any moment exactly how he is being duped, a dubious fence Conrad (Maury Chaykin), and a muscle man Thibadeaux (Ving Rhames) who may be playing both sides against each other.

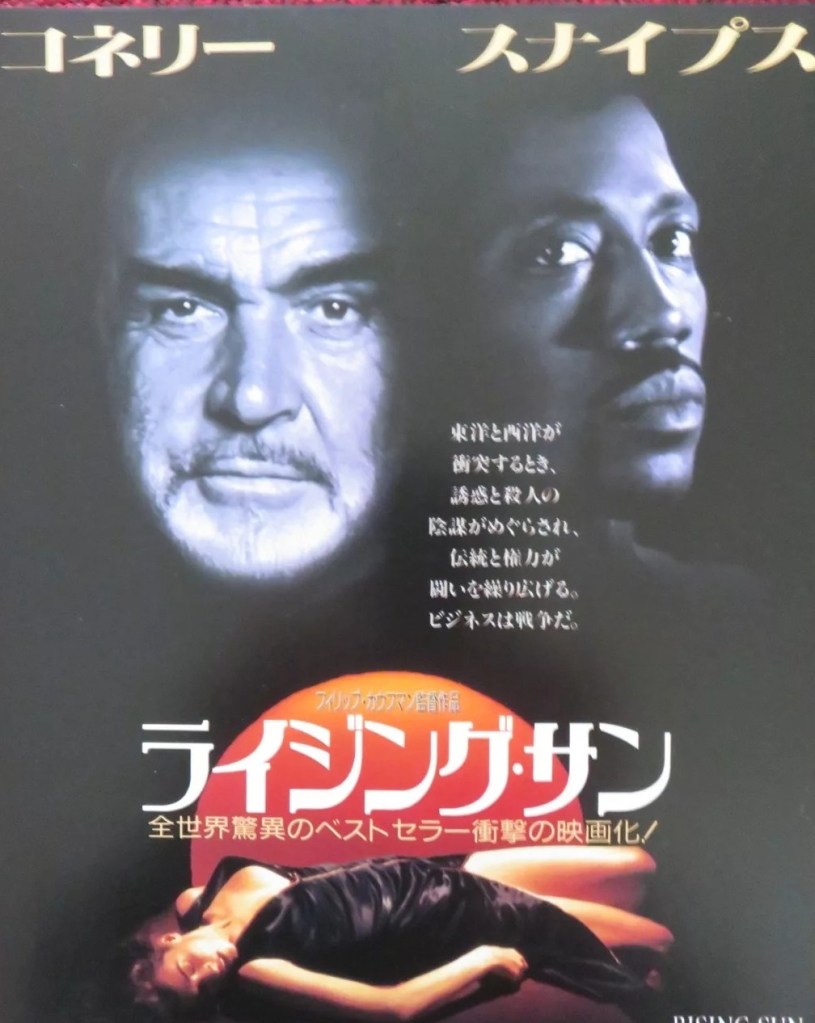

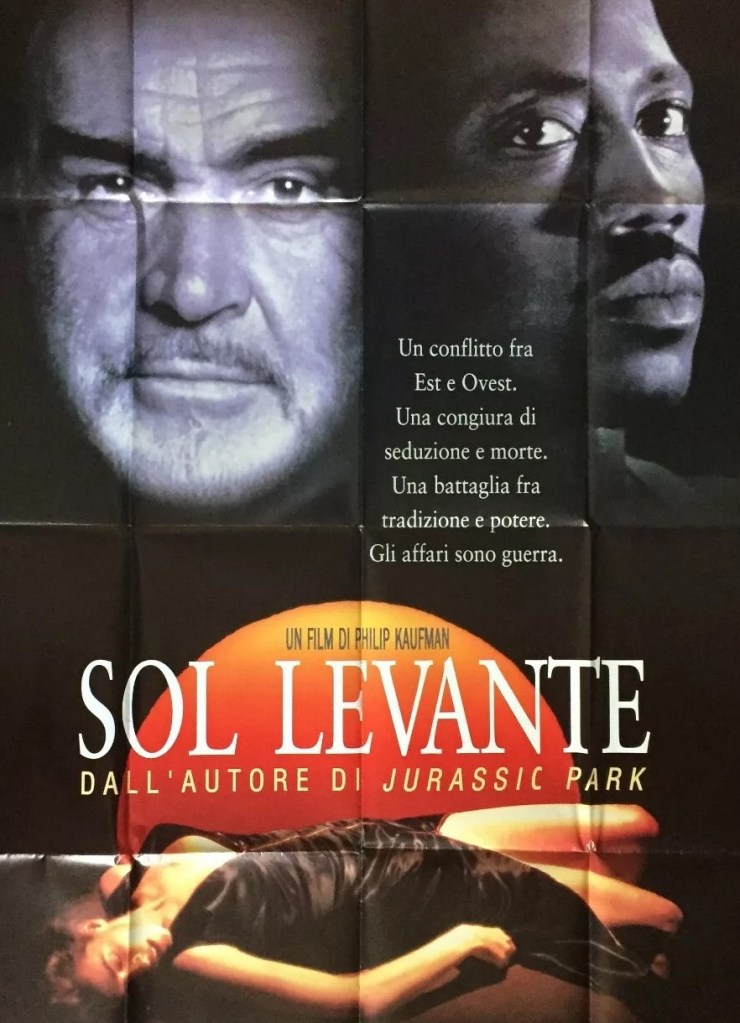

After more than three decades, Sean Connery maintained a position in the top echelons of the box office marquee, in part because of the size of his global audience, but mostly because he continuously delivered. Every three years in the 1990s he knocked out a big one. The Hunt for Red October (1990), Rising Sun (1993) and The Rock (1996) easily offset any movies that produced less.

Catherine Zeta-Jones had announced her candidacy for stardom through a scintillating turn as the foil for Antonio Banderas in The Mask of Zorro (1998) and had she taken a more blatant approach to stardom could easily have been a letter-day femme fatale in the style of Lana Turner or Ava Gardner, but her screen persona encompassed considerably greater guile and discretion.

John Wayne, to compensate for any age difference between himself and the target of potential romance, always came over as all shy and diffident in making an approach, ensuring that it was the woman who did all the running so he wasn’t presented as some kind of creepy predator. Here Sean Connery avoids the complications of seduction and a May-December situation by playing the paternal card, covering up Gin’s half-naked sleeping body, tucking her hair behind her ear.

So where the entire middle act of The Thomas Crown Affair revolved around romance and the final act depended on a will she/won’t she scenario, this steers largely clear of such confusion, concentrating instead on the heists, with the background figures creating such distraction as was necessary to heighten the tension. From the opening sequence of a cat burglar abseiling down a skyscraper and removing an entire window to gain access to the final time-dependent heist, it’s a thrilling ride.

As you’ll be aware I’m a huge fan of Sean Connery and of his minimalist style of action. There were two standouts here for me, both blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moments. You’ve seen plenty actors doing extended stretches or walking around or some such physical mugging to show that they’ve been awake for too long worrying over a problem. Connery’s concession to that is merely a clever trick with his eyes. Then there’s a scene where Gin is trying to put the squeeze on him and one look from him shows that she’s going to fail.

Sean Connery and Catherine Zeta-Jones have a screen chemistry that, unfortunately, was never repeated. British director Jon Amiel (Copycat, 1995) sticks to the screenplay, allowing the romance to seep out around the edges.

Top-notch stuff. Not quite in the Topkapi (1964) category but not far off.