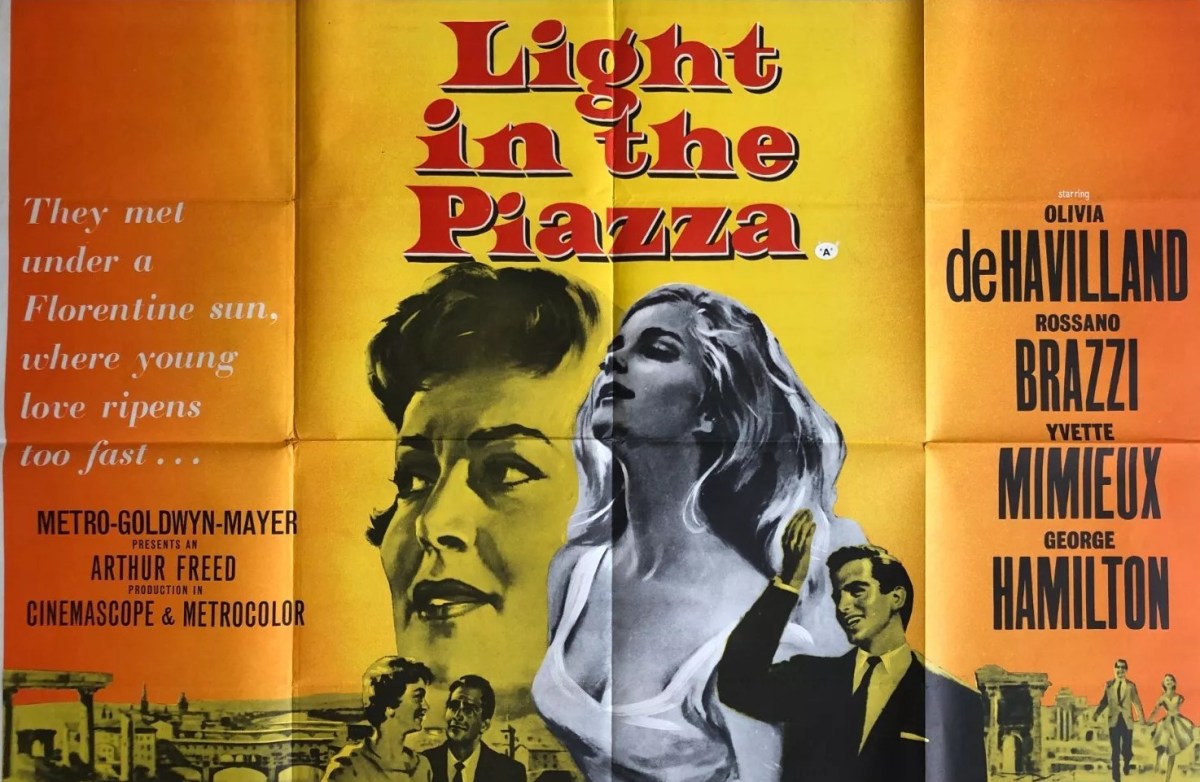

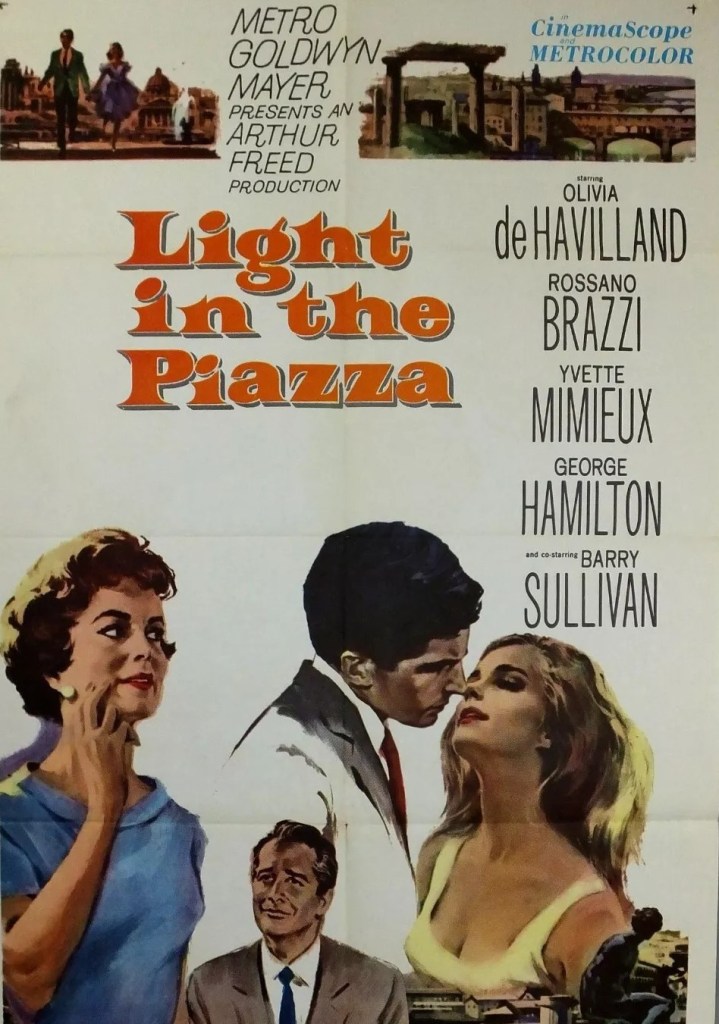

Will resonate more strongly today. Never intended as a light-hearted confection, despite the obvious premise of young love catching fire in Italy, this was a bold picture in its day and a more subtle examination of the wider impact of mental illness than those later movies set in institutions such as Lilith (1962) or Shock Treatment (1964). Bold, too, of Olivia de Havilland to take on a role that is so transparently maternal. Instead of her middle-aged character succumbing to romantic opportunity as the billing might suggest, to a holiday affair with a rich handsome Italian, she is first and foremost a mother.

Initially, standard romance meet-cute as young Italian Fabrizio (an unlikely George Hamilton) catches the runaway hat of young blonde Clara (Yvette Mimieux) in a piazza in Florence. His ardent pursuit is thwarted at every turn by Clara’s mother Meg (Olivia de Havilland). At first this appears to be for the most obvious of reasons. Who wants their naïve daughter to be swept away by a passionate Italian with heartbreak and possibly worse consequence (what mother does not immediately conjure up pregnancy?) to come.

Sure, Clara seems flighty and a tad over-exuberant and perhaps prone to tantrums but then back in the day this was possibly just an expression of entitlement by rich indulged young women. Turns out there’s a more worrying cause of her sometimes-infantile behavior. She was kicked in the head by a pony and has the mental age of a child of ten. If she is not protected, she might end up as prey to any charming young man.

Clara needs tucked up in bed with a stuffed toy, and her mother to check the room for ghosts and read her a bedtime story before she can go to sleep. Even when Fabrizio’s credentials check out – his father Signor Naccarelli (Rossano Brazzi) vouches for his good intentions, but, in the way of the passionate Italians, would not want to stand in the path of true love.

Clara’s father Noel (Barry Sullivan) is the one who spells out the reality. That pony didn’t just kick his daughter in the head it “kicked the life out of” his marriage. His wife lives in a dreamland, hoping for a miracle, and if that is not forthcoming quite happy to live with a daughter who never grows up. He wants to send her to “a school,” convincing himself it’s “more like a country club.”

Meg fights her own feelings that she knows better than her daughter and that love will not provide the cure, at the same time as batting away the affections of the elder Naccarelli. When she finally gives in to her daughter’s desire, wedding plans fall apart at the last minute when Naccarelli Snr discovers that his 20-year-old son is marrying not, as he imagined, a woman of roughly the same age or slightly younger, but actually someone six years older. Eventually, the wedding goes ahead. Meg convinces herself she did the right thing in permitting the marriage to go ahead.

But this is one of those happy ever afters that don’t quite wash and you might find yourself wondering exactly how it played out when the husband discovered exactly what kind of wife she had. Her instability isn’t genetic so no danger of a subsequent child encountering the same issue. And having to care for someone other than herself might well bring out the same level of maternity as her mother shows, but equally clearly Fabrizio is unaware of exactly what he’s taking on. How will he feel when asked to read her a bedtime story or scour the cupboards for imaginary monsters.

The movie didn’t do well enough to warrant a sequel – audiences expecting romantic confection were disappointed – and just hope Clara didn’t turn into the kind of inmate seen in Lilith and Shock Treatment.

Still, takes a very realistic approach to the problems of someone with such problems maturing into adulthood.

The Oscar-garlanded Olivia de Havilland (two times winner, three times nominee), in her first picture in three years, clearly didn’t want to see out her maturity in those May-December roles that others of her age fell prey to. She is excellent here, no attempt to dress herself up as a sex bomb, and refreshing to see her approach. Yvette Mimieux (Diamond Head, 1962) is excellent as the confused youngster. George Hamilton (The Power, 1968) lets the side down with his speaka-da-Italian Italian but Rossano Brazzi (The Battle of the Villa Fiorita, 1965), who is Italian, has no trouble with the lingo or with being a smooth seducer.

Director Guy Green (Diamond Head, 1962) adds in some unusual Florentine tourist color, but doesn’t shirk the difficult storyline. Julius J. Epstein (Casablanca, 1942) wrote the script.

Worth a look