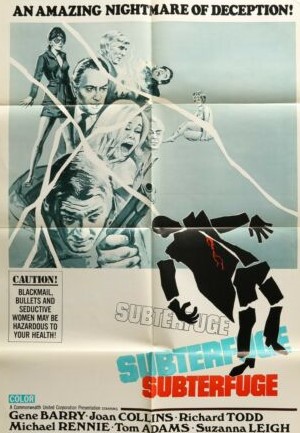

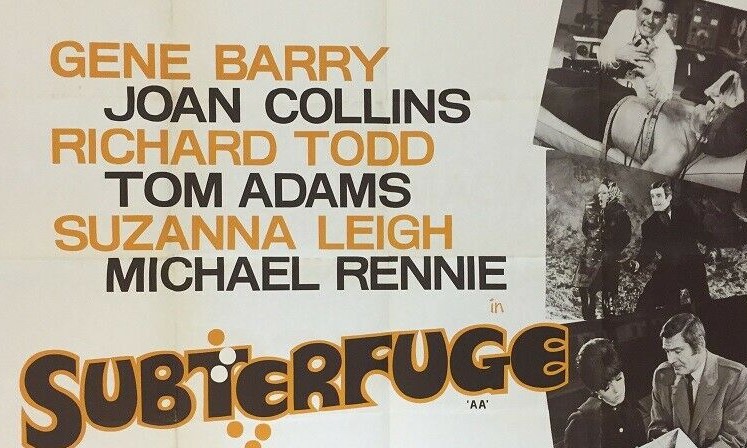

Worth seeing alone for super-slinky leather-clad uber-sadistic Donetta (Suzanna Leigh) who delights in torturing the daylights out of any secret agent who crosses her path, in this case Michael Donovan (Gene Barry). She’s got a neat line in handbags, too, the poisonous kind. Two stories cross over in this London-set spy drama. American Donovan (Gene Barry) is under surveillance from both foreign powers and British intelligence. When his contact comes into unfortunate contact with a handbag, he finds himself on the sticky end of the attention of Shevik (Marius Goring) while at the same time employed by the British spy chief Goldsmith (Michael Rennie) to find the mole in their camp.

The three potential suspects are top-ranking intelligence officers: Col. Redmayne (Richard Todd), British spy Peter Langley (Tom Adams) and backroom underling Kitteridge (Colin Gordon). On top of this Langley’s wife Anne (Joan Collins) adds conscience to the proceedings, growing more and more concerned that the affairs of the secret state are taking too much precedence over her marriage.

The hunt-the-mole aspect is pretty well-staged. Kitteridge always looks shifty, keenly watching his boss twisting the dials on a huge office safe containing top secret secrets. Langley is introduced as a villain, turning up at Shevik’s with the drugs that are going to send Donovan to sleep for eight hours for transport abroad in a trunk. But he turns out to be just pretending and aids Donovan’s innovative escape. Charming but ruthless Redmayne is also under suspicion if only because he belongs to the upper-class strata (Burgess, Philby and Maclean etc) that already betrayed their country.

In investigating Langley, Donovan fixes on the wife, now, coincidentally, a potential romantic target since her husband is suing for divorce. She is particularly attracted to Donovan after he saves her son from a difficult situation on the water, although that appears manufactured for the very purpose of making her feel indebted. However, the couple are clearly attracted, although the top of a London bus would not generally be the chosen location, in such glamorous spy pictures, for said romance to develop.

As you will be aware, romance is a weak spot for any hard-bitten spy and Shevik’s gang take easy advantage, putting Anne, her son and Donovan in peril at the same time as the American follows all sorts of clues to pin down the traitor.

This is the final chapter in Gene Barry’s unofficial 1960s movie trilogy – following Maroc 7 (1967) and Istanbul Express (1968) – and London is a more dour and more apt climate for this more down-to-earth drama. Forget bikinis and gadgets, the best you can ask for is Joan Collins dolled up in trendy min-skirt and furs. Gene Barry, only too aware that London has nothing on Morocco or Istanbul in the weather department, dresses as if expecting thunderstorms, so he’s not quite the suave character of the previous two pictures, but that does not seem to dampen his ardor and the gentle romantic banter is well done.

Joan Collins, in a career trough after her Twentieth Century Fox contract ended with Esther and the King (1960), has the principled role, determining that the price paid by families for those in active secret service is too high. No slouch in the spy department himself, essaying Charles Vine in three movies including Where the Bullets Fly (1966), Tom Adams plays with audience expectations in this role.

It’s a marvelous cast, one of those iconic congregations of talent, with former British superstar Richard Todd (The Dam Busters, 1955) and Michael Rennie, television’s The Third Man (1959-1965), Marius Goring (The Girl on a Motorcycle, 1968) and Suzanna Leigh (The Lost Continent, 1968) trading her usual damsel-in-distress persona for a turn as terrific damsel-causing-distress.

Shorn of sunny location to augment his backgrounds, director Peter Graham Scott (Bitter Harvest, 1963) turns his camera on scenic London to take in Trafalgar Square, the zoo, Royal Festival Hall, the Underground, Regent’s Park with the usual flotilla of pigeons and ducks.

Get slinky.