Intellect can present as powerful a sexual magnetism as wealth. And for young women, unlikely to come into the orbit of powerful movie magnates or wealthy businessmen, they are most likely to experience abuse of power in academia, especially in top-notch universities like Oxford and Cambridge or Harvard and the Sorbonne.

Young students, unsure of their place in the world, depend on praise for their self-esteem. To be on the receiving end of flattery from a renowned scholar, a young person (males included) might be willing to overlook other unwanted attention. For young women and men accustomed to being assessed on looks alone this might be a drug too powerful to ignore.

The British system ensured that potential prey was delivered to potential predators. As well as attending lectures, each student was allocated a tutor and could spend a considerable amount of time with them in private in congenial surroundings behind closed doors. And since essays marked by tutors played a considerable element in an overall mark, there was plenty of opportunity for transactional sex.

And it was easy for women to think they wielded the sexual power. I once employed a woman who boasted that she had seduced her university tutor, little imagining that that took any opposition on his part, and that, in reality, she was just another easy conquest.

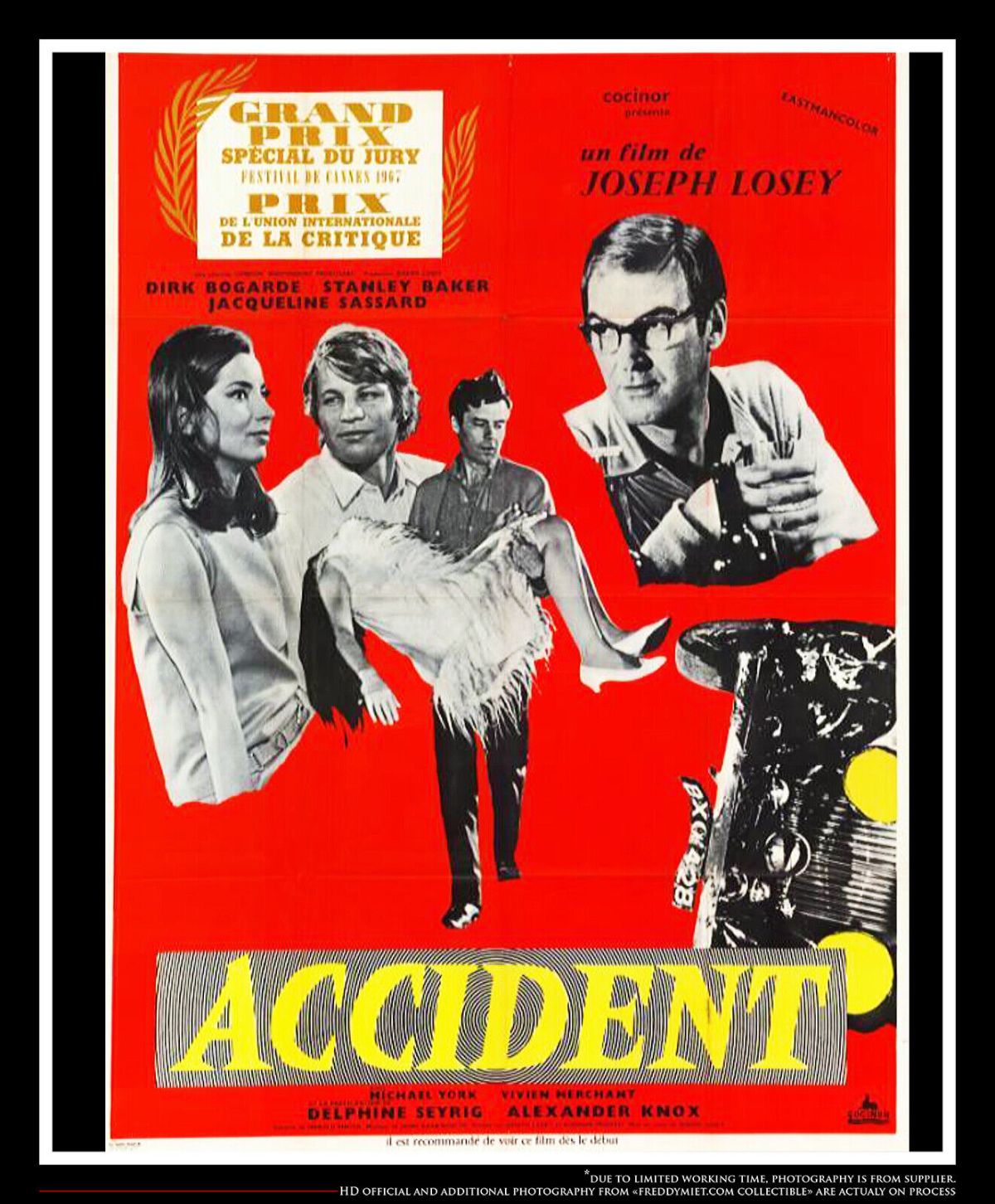

So you might be surprised to learn that when this movie about inappropriate behavior in a university of the caliber of Oxford appeared, nobody gave a hoot about the grooming and exploitation of young Austrian Anna (Jacqueline Sassard) by two professors, Stephen (Dirk Bogarde) and Charley (Stanley Baker).

The story is told in flashback in leisurely fashion. Hearing a car crash outside his substantial house in the country, Stephen finds inside the vehicle an injured Anna and her dead boyfriend William (Michael York). Then we backtrack to Anna’s arrival in Oxford, and how the love quadrangle is created. The presence of William suggests Anna has predatory instincts, but there is no sign of sex in their relationship, rather that he is forever frustrated at being kept on a leash and clearly suspecting he is losing out to others.

Stephen, a professor of philosophy, no higher calling in academe, endless discussion on the meaning of life manna to every student, has a purported happy home life, wife Rosalind (Vivien Merchant) pregnant with their third child. He’s no stranger to infidelity, reviving an affair with the estranged daughter Francesca (Delphine Seyrig) of a college bigwig (Alexander Knox).

But he can’t quite make his move on Anna, despite idyllic walks in the fields and their hands almost touching on a fence. The uber-confident Charley, novelist and television pundit in addition to academic celebrity, has no such qualms and seduces her under the nose of his friend and sometime competitor.

When opportunity does arise for Stephen it does so in the most horrific fashion and, that he takes advantage of the situation, exposes the levels of immorality to which the powerful will stoop without batting an eyelid.

The web Stephen is trying to weave around his potential victim is disrupted by William and Charley and if any anguish shows on Stephen’s face it’s not guilt at the grief he may cause or about his own errant behavior but at the prospect of losing a prize.

Director Joseph Losey (Secret Ceremony, 1968) sets the tale in an idyllic world of dreaming spires, glasses of sherry, tea on the lawn, glorious weather, punting on the river, old Etonian games, the potential meeting of minds and the flowering of young intellect. The action, like illicit desire, is surreptitious, a slow-burn so laggardly you could imagine the spark of narrative had almost gone out.

Stephen is almost defeated by his own uncontrolled desire, taking advantage of his wife entering hospital for childbirth, the children packed off elsewhere, to have sex with Francesca, not imagining that Charley will take advantage of an empty house.

And the young woman as sexual pawn is given further credence by the fact that at no point do we see the events from her perspective.

Anguish had always been a Dirk Bogarde (Justine, 1969) hallmark and usually it served to invite the moviegoer to share his torment. So it’s kind of a mean trick to play on the audience to discover that this actor generally given to playing worthy characters is in fact a sleekit devious dangerous man. Of course, the persona reversal works very well, as we do sympathise with him, especially when relegated to second fiddle in the celebrity stakes to Charley and humiliated in his own attempts to gain television exposure.

Stanley Baker (Sands of the Kalahari, 1965) was the revelation. Gone was the tough guy of previous movies. In its place a charming confident winning personality with a mischievous streak, a far more attractive persona when up against the more introspective Bogarde.

Jacqueline Sassard (Les Biches, 1968) is, unfortunately, left with little to do but be the plaything. There’s an ambivalence about her which might have been acceptable then, but not now, as if somehow she is, with her own sexual powers, pulling three men on a string. In his debut Michael York (Justine, 1969) shows his potential as a future leading man.

You might wonder if Vivien Merchant (Alfred the Great, 1969) was cast, in an underwritten part I might add, because husband Harold Pinter (The Quiller Memorandum, 1966) wrote the script and Nicholas Mosley, who had never acted before, put in an appearance because he wrote the original novel.

Losey, a critical fave, found it hard to attract a popular audience until The Go-Between (1971) and you can see why this picture flopped at the time despite the presence of Bogarde and Baker. And although it is slow to the point of infinite discretion, it’s not just a beautifully rendered examination of middle class mores, and a hermetically sealed society, but, way ahead of its time, and possibly not even aware of the issues raised, in exploring abuse of power, a “Me Too” expose of the academic world.

The acting and direction are first class and it will only appear self-indulgent if you don’t appreciate slow-burning pictures.