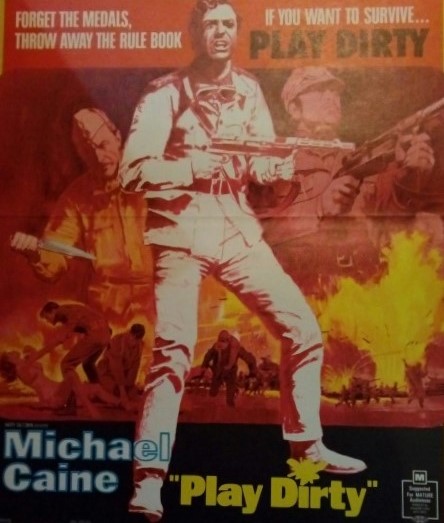

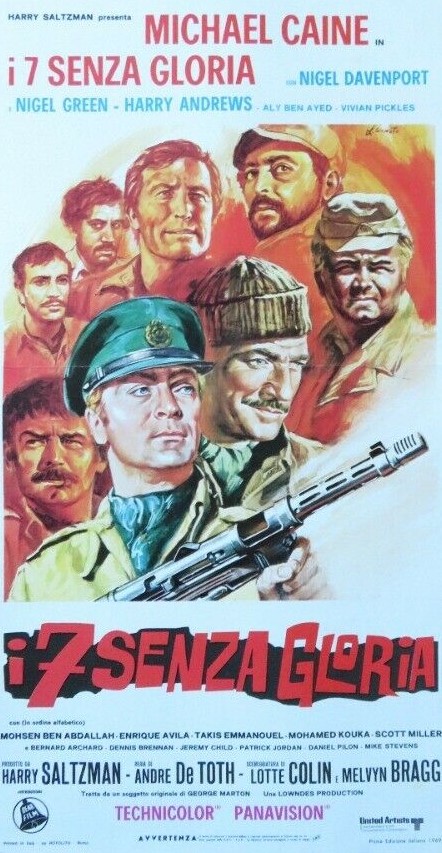

Heroism is a handicap in this grimly realistic, brutally cynical, ode to the futility of war. David Lean would have struggled to turn this stone-ridden desert into anything as romantic as his Lawrence of Arabia (1962) though he might have recognized the self-serving glory-hunting superior officers.

There’s a murkiness at the outset that is never quite clarified. You could easily assume that the long-range bunch of saboteurs led by Captain Leach (Nigel Davenport), with the peculiar habit of losing new officers, was involved in something more nefarious rather than doing its utmost to disrupt Rommel’s supply lines in North Africa during World War Two.

Brigadier Blore (Harry Andrews) appoints raw officer Captain Douglas (Michael Caine) to take charge of the next mission – a 400-mile trek to blow up a fuel dump. Col Masters (Nigel Green), in overall charge of the commandos, bribes Leach to ensure Douglas comes back alive. Blore is using this small unit as a decoy before deploying a bigger outfit to complete the mission with the singular aim of snaffling the glory for himself.

Leach proves insolently disobedient, forcing Douglas at one point to draw his weapon on his crew. But when it comes down to a question of heroism vs survival, Leach takes control at knifepoint, preventing Douglas going to the aid of the larger outfit when ambushed by Germans.

It’s mostly a long trek, somewhat bogged down by mechanics of desert travel. You’ll be familiar with the process of rescuing jeeps buried in sand dunes and of personnel sheltering from sandstorms, so nothing much original there. What is innovative is the terrain. Stones aren’t conveniently grouped together, edges softened by time, as on a beach. They’re jagged- edged and less than a foot or so apart so as to more easily shred tires. So there’s a fair bit of waiting while tires are replaced.

Some decent tension is achieved through sequences dealing with mines – threat removed in different fashion from Tobruk (1967) or, for that matter, The English Patient (1996) – and in crawling under barbed wire. But that’s undercut by the sheer brutality of the supposed British heroes slaughtering an Arab encampment and viewing a captured German nurse as an opportunity for rape.

A couple of twists towards the end raise the excitement levels but it’s less an action picture than a study of the ordinary soldier at war. Captain Douglas, the only character worth rooting for, soon loses audience sympathy by foolish action and behavior as criminal as his charges.

A few inconsistencies detract. For a start, there’s no particular reason to assign Douglas to this patrol. Primarily a backroom boy, he’s put in charge because he was previously an oil executive. But it hardly takes specialist knowledge to lob bags of explosives at oil drums. And the ending seems particularly dumb. I can’t believe Douglas and especially the canny Leach, both dressed in German uniforms, would consider walking towards the arriving British forces waving a white flag rather than stripping off their uniforms and shouting in English to make themselves known to the trigger-happy British soldiers.

And a good chunk of tension is excised by the bribery. Why not leave the audience thinking that at any moment the bloody-minded Leach would dispatch an interfering officer rather than offering him a huge bounty (£75,000 at today’s prices) to prevent it?

It suffers from the same affliction as The Victors (1964) in that it sets out to make a point and sacrifices story and character to do so. That individuals will be pawns in pursuit of the greater good or glory is scarcely a novel notion.

Having said that, I thought Michael Caine (Gambit, 1966) was excellent in transitioning from law-abiding officer to someone happier to skirt any code of conduct. There’s no cheery Cockney here, more the kind of ruthlessness that would emerge more fully grown in Get Carter (1971). Nigel Davenport (Life at the Top, 1965) adds to his portfolio of sneaky, untrustworthy characters. Equally, Harry Andrews (The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1968) has been here before, the kind of upper-class leader who behaves like a chess grandmaster.

In his first picture in half-a-decade Andre de Toth (The Mongols, 1961) produces a better result than you might expect from the material – screenplay courtesy of Melvyn Bragg (Isadora, 1968) and in her only known work Lotte Colin, mother-in-law of producer Harry Saltzman – and creates some exceptionally tense scenes and the occasional stunning image.

Anti-war campaigners line up here.