Absorbing duel of minds between two autocrats obsessed with their own glory and needs and dealing with dissension in the ranks. That it takes place during the Battle of the Bulge turns out to be less of a dramatic hindrance though you maybe have to suspend disbelief in the notion that any resistance fighters might take time out from trying to sabotage Germans to help rescue a bunch of whining, pampered non-combatants with no strategic value whatsoever.

Once you accept that the U.S.O. would deem a classical orchestra the best way to entertain the troops rather than Betty Grable or Bob Hope then you’re halfway there.

Anyway, the Germans launching an offensive in December 1944 by accident capture the classical orchestra led by world-famous conductor Lionel Evans (Charlton Heston). The Germans are under orders to take no prisoners so as not to divert vital troops during this last-stage effort to extend the war, so under the direction of Colonel Arndt (Anton Diffring) the musicians face a firing squad until General Schiller (Maximilian Schell) happens to pop his head out of his window and recognize his hero, Evans.

Death is temporarily averted while Schiller purrs over his captive. But Evans, still high on principle and arrogance, refuses to comply with Schiller’s request to play a concert for him during a delay in the battle as, the Germans, hit by fuel shortage, are unable to continue their campaign and therefore have time on their hands. There ensues the aforesaid duel of minds plus various demonstrations of disloyalty and ruthlessness.

The joy here is the dialog because there’s not much else going on, beyond a half-hearted attempt to escape, and the tension doesn’t rachet up until Evans realizes Schiller is only keeping them alive until the concert, after which they will be turned over to the trigger-happy Arndt, who lacking any subtlety, has already begun to dig a mass grave in full view of the trapped self-proclaimed neutrals.

It’s almost a parade of bon mots as each of the leaders tries to top the other’s sentences, and not in merely a clever manner, but with full-blown fascinating argument, in part about the different outlooks of each country, but also about their contradictions, and it’s a rare movie that can hold your attention just through dialog unless it’s set in a courtroom. But, here, Evans isn’t so much arguing for the suspension of a death penalty, for example, but in a remote high-mindedness complaining that, well, there’s no other word for it, that it’s just “unfair” as if the Geneva Convention has a special clause regarding classical musicians.

Maybe it does, given these are Americans, though not in uniform, which might be a point in their favor. But any commander would be correct in assuming they could, through courageous action, perform an act of sabotage or at the very least, as I mentioned, tie up vital resources.

Matters are complicated because Arndt, less self-indulgent than his superior, goes behind Schiller’s back to rat him out to HQ in Berlin while nameless persons within the orchestra are clearly in cahoots with the Germans. And you can’t blame them either. Arndt believes Schiller’s actions could compromise the attack, the orchestra traitors that Evans’ defiance will get them all killed. Evans is quite happy to sacrifice former lover Annabelle (Kathryn Hays) to keep the German commander, who has taken a fancy to her, happy.

Matters are complicated by the presence in the orchestra ranks of two U.S. soldiers in uniform, who feel duty bound to find a way out, so there’s a bit of the kind of action you’d get in a heist movie where an audience listens to classical music while above them a cat burglar is divesting them of their jewels. Here, the two soldiers are clambering up the innards of a church to the roof to scope out the territory and then attempt escape using a home-made rope made up of scarves and nylons etc.

As it becomes obvious that there is no point in Evans playing for time, the tension and turmoil does increase as that unfilled mass grave beckons. Doesn’t play out the way you’d expect, a couple of neat twists keeping cliché at bay.

But, as I said, the primary interest is the verbal battle between two refined minds convinced they are the most important people on the planet. The only standout scenes not involving Evans concern Schiller’s “seduction” of Annabelle and the playing of the American national anthem by one of the soldiers, planted in the orchestra, who Arndt suspects, from his age (too young to be in such august company unless a musical prodigy), doesn’t fit in.

Charlton Heston (Number One, 1969) and Maximilian Schell (Topkapi, 1964) are both superb as flawed characters. There’s a rare movie appearance for Kathryn Hays (Ride Beyond Vengeance, 1966) and another chance to see Leslie Nielsen (Beau Geste, 1966) before he became comedy catnip.

But it’s the script by James Lee (Banning, 1967) and Joel Oliansky (The Todd Killings, 1971), that really delivers, although I’m guessing that the best lines came directly from the source novel, The General by Alan Sillitoe (Saturday Night and Sunday Morning). Directed by Ralph Nelson (Once a Thief, 1965).

Rare to get a movie that relies so much on script and actors on such top form.

Underrated gem.

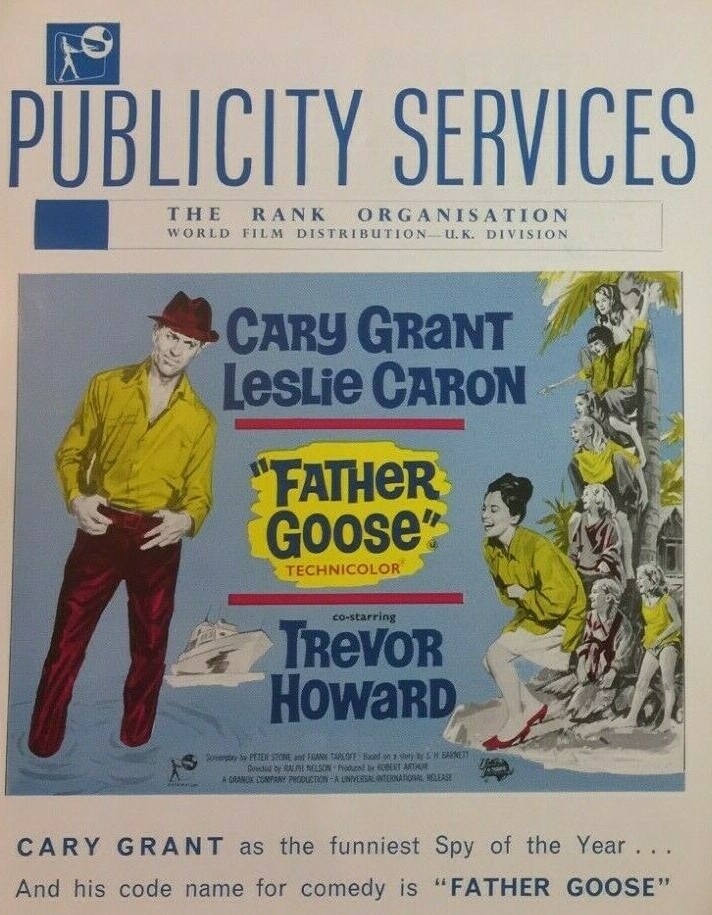

PREVIOUSLY REVIEWED IN THE BLOG: Charlton Heston in Diamond Head (1962), 55 Days at Peking (1963), Major Dundee (1965), The War Lord (1965), Khartoum (1966), Planet of the Apes (1968), Number One (1969); Maximilian Schell in Judgement at Nuremberg (1961), Topkapi (1964), Fate is the Hunter (1964), Father Goose (1964), Return from the Ashes (1965), The Deadly Affair (1967), Krakatoa -East of Java (1968); Ralph Nelson directed Soldier in the Rain (1963), Once a Thief (1965), Duel at Diablo (1966) and Soldier Blue (1970).