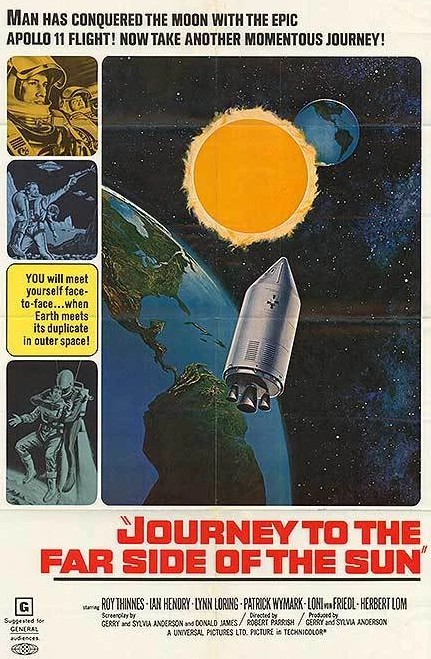

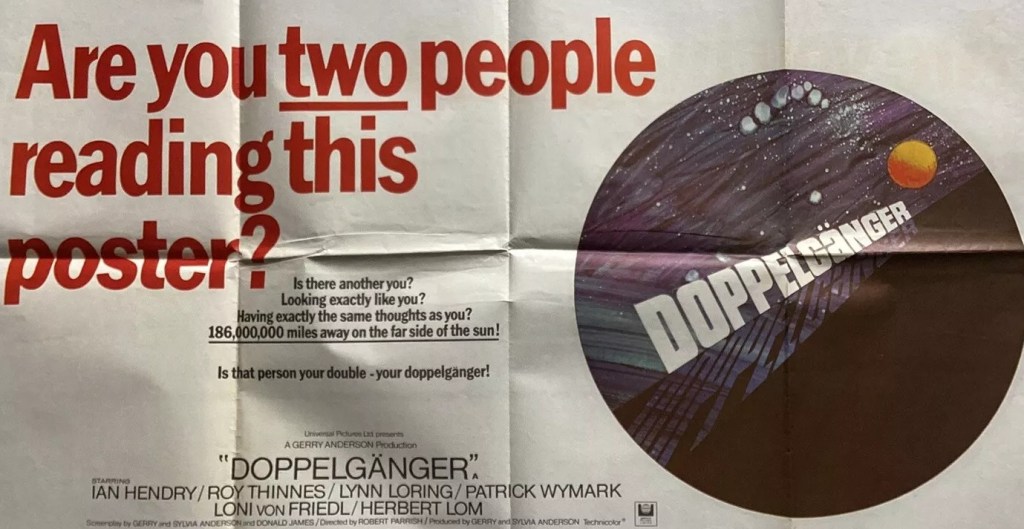

Bring Gerry and Sylvia Anderson into the equation and it’s a straightforward free pass of the cult kind. For the fanboys, the inventors of Supermarionation (Thunderbirds Are Go!, 1966) live on an exalted plane immune from criticism. however, sci fi buffs have tended to be less than impressed by the pair’s first venture into (to use a Walt Disney phrase) “live-action.” So response swings between these extremes. I fit into neither category so I come at this with something of an open mind and for a variety of reasons found it a far more enjoyable experience than I had anticipated, though I hazard a guess that on the big screen the flaws in the special effects would have been more obvious.

Some aspects even have a contemporary chime, the X-ray security screening machines, for example, and the fact that there’s no such actual entity called Europe and if you want to advance a project you have to navigate your way through the representatives of several countries as well as the hovering financial weight of the United States, bristling at being asked to pay more than its share but worried about being excluded.

And there’s no ice-cool scientific boffin. Instead we have the choleric, not to mention bombastic, Jason Webb (Patrick Wymark). Nor do non-combatants scoot through training. The rigors potential astronauts are put through in the likes of The Right Stuff (1983) or Apollo 13 (1995) are nothing to the body-wringing and mind-blowing experience of John Kane (Ian Hendry).

His companion space buddy Col John Ross (Roy Thinnes) is well-drawn for a sci fi adventure. He’s worried that exposure to radiation and worse in space has knocked his masculinity on the head, his wife Sharon (Lynn Loring) complaining it has left him sterile. Though it turns out she’s a wily creature, secretly using contraception.

We also get a spy, Dr Hassler (Herbert Lom), and it’s not so much that he has a gadget – a mini camera secreted in a false eyeball – than the detail involved in him retrieving the film. In most movies there would be no gap between the reveal of the gadget and the production of its secrets. But here Dr Hassler has to go through a whole procedure, dipping the eyeball into four solutions and dabbing it with this and that, before he can view a single frame.

The picture breaks down into a straight three-act vehicle. The first section getting to lift off, then the journey including the kind of phantasmagorical event you found in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and which even Christopher Nolan relied upon in Interstellar (2014), and arrival.

Most sci fi movies play fast and loose with audiences, rarely remaining true to the logic of their invented worlds or concepts. This sticks to its original notion even if that means ending up with a distinctly downbeat ending. Initially, the astronauts are searching for a new planet, whose orbit is similar to Earth, but on the other side of the sun. This being the year 2068, distance is no object and they reckon it’s a six-week return trip.

But what the astronauts discover on arrival at the new planet is a nightmare situation, that in terms of ability to drive you mad skews close to enigmatic British TV series The Prisoner (1967) or Lost (2004-2010) before it jumped the shark. Ross and Kane have landed on a doppelganger planet and the movie takes this world to its logical conclusion. It’s the real parallel universe, or multiverse in the current vernacular, except everything happens the same as on Earth.

So the choleric Webb initially accuses the astronauts of cowardice, to have turned back and failed to complete their mission which would have led them to our Earth. Doppelganger literally means mirror image which eventually explains why writing goes left to right and everything is a step out of normal kilter. Identical except not quite. And stuck in a world where everything that seems real is one step away from your known reality. The kind of situation that would have been created by a mad scientist intent on torturing minds.

Ross determines to attempt to return to Earth but that means connecting what remains of his spaceship with a space vessel made on the new planet but the parts that should fit exactly don’t fit because they have designed in mirror fashion. So that’s it for your chances of a happy ending.

Left me with a nightmare feeling, the ultimate what if. As far as stings in the tail go, comparable with Planet of the Apes (1968).

For the concept as much as the clever detail, I’ve given it a higher mark than maybe it deserves.