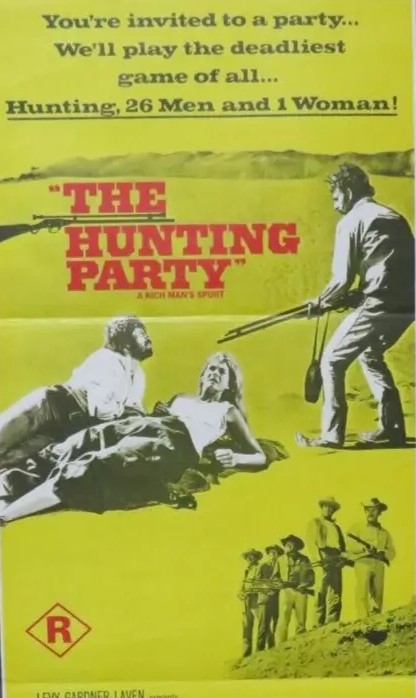

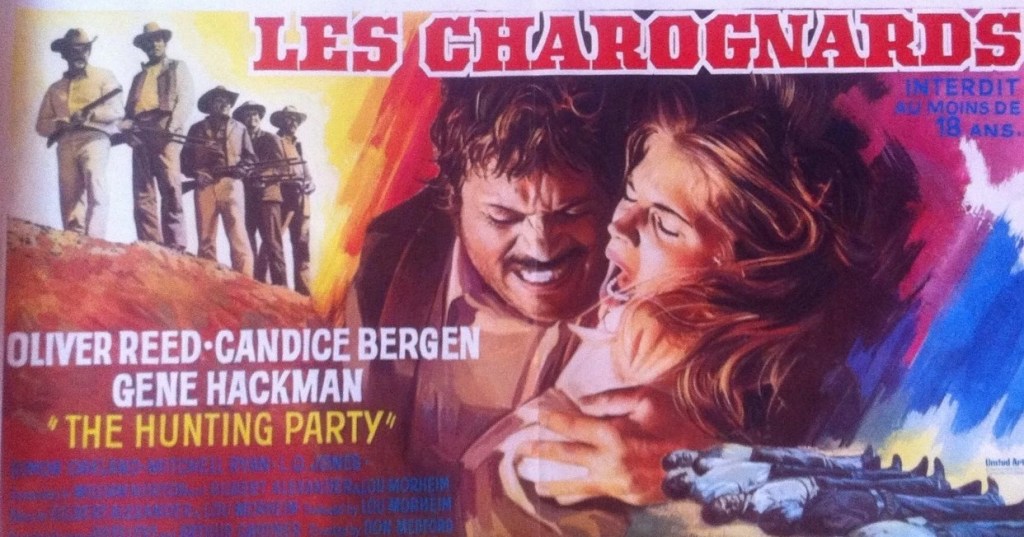

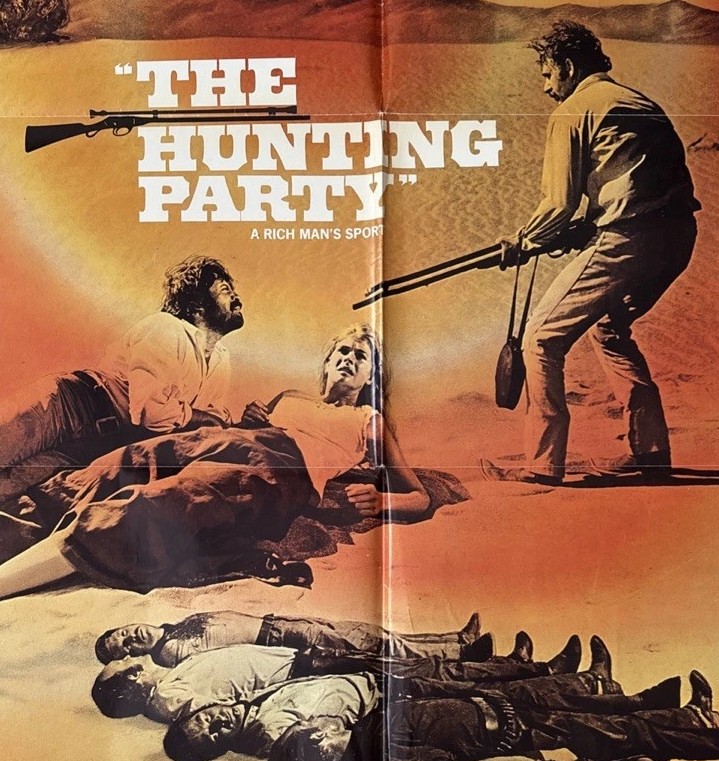

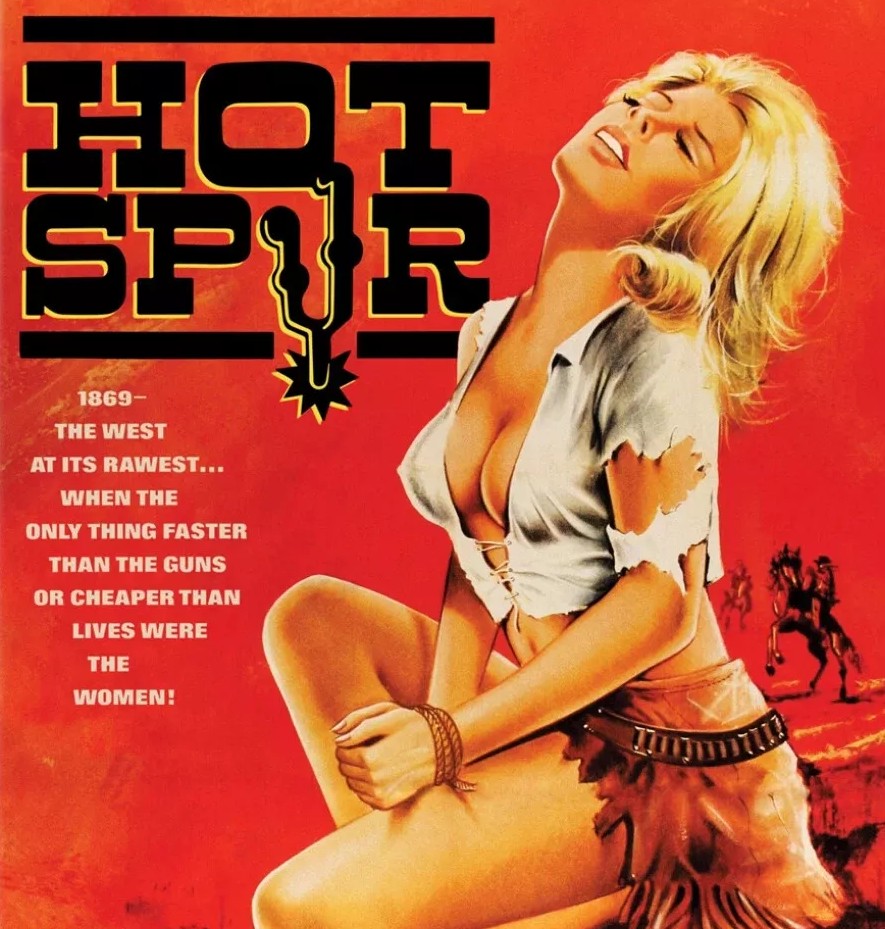

Blame the algorithm. Once I had to my great surprise found The Hunting Party (1971) on Amazon Prime the streamer decided that my next port of call should be another rape-filled western. There are only two things to recommend this – firstly, it makes The Hunting Party look like a masterpiece, and secondly it was filmed at the Spahn Ranch made famous by Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) and as the place where the Charles Manson gang hung out before going on a murder spree.

One element of this picture will chime with the contemporary audience. Here, rape is used as a weapon, an unfortunate development in the last half century during a variety of vicious wars. As ever, woman is the innocent victim while man has convinced himself this is not only necessary but justified.

There’s maybe another echo if you want to be generous – of the sequence in Once Upon a Time in the West (1969) where Harmonica (Charles Bronson) is forced to witness the death of his older brother. Here Mexican stable hand Carlo (James Arena) witnesses the multiple rape and beating of his older sister who subsequently commits suicide. So he’s on a mission to track down the perpetrators.

Which leads him to the O’Hara ranch, where he is treated with racist and physical abuse. Ranch owner Jason (Joseph Mascolo) handles wife Susan (Virginia Gordon) badly, blaming her for not providing him with a son and heir. Their love-making is on the rough side and she seeks comfort among the cowhands, who prefer keeping their jobs to a roll in the hay with the boss’s wife.

Carlo kidnaps her. And at first you think she’s going to be used as bait to attract Jason, the last of the rapists of his sister, to a remote mountain shack. But, in fact, Carlo plans to eliminate pretty much the entire complement of ranch hands, hiding weapons at various ambush points on the trail and planting a bear trap in the ground.

But he’s got worse in mind. And apologetic though he is towards Susan, his plan is to make her suffer like his sister, which means tying her up, raping her and striping her back with a whip. The only good bit, if you can call it that, in this picture is that at the end Susan knifes to death her husband and escapes.

There’s one other bit that initially looks good and then tumbles into incomprehension. Jason has sent an advance scout up the mountain and told him to fire one shot if his wife is up there and two if she’s not. The cowboy doesn’t get the chance, Carlo killing him with two shots. So, registering this, Jason believes they’re on the wrong trail but then for no apparent reason continues up the same route.

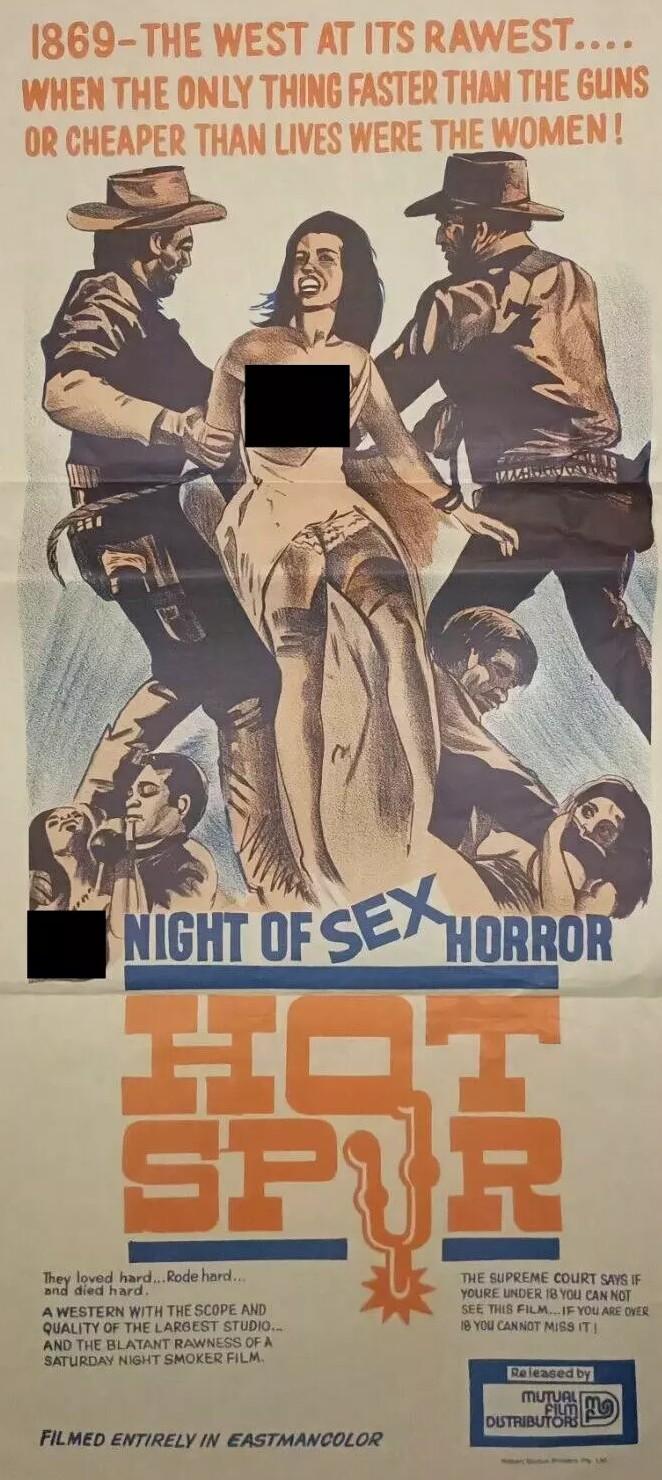

From the amount of sexuality and nudity on show I guess, given the times when Hollywood was still only nibbling away at the edges of what was permissible, this was made for an entirely different audience than the standard fan of westerns. All women are present just to be used and abused.

Directed by one Lee Frost, whom imdb rates as “one of the most talented and versatile filmmakers in the annals of exploitation cinema.” Cowritten with producer Bob Cresse.

As it happens, those Amazon Prime algorithms did send me to a whole horde of westerns, some of which like Hombre (1967) and Support Your Local Sheriff (1969), I’ve already reviewed here. I’ll plunder this stack some more but take a more judicious view of what I watch.

Ugharama.