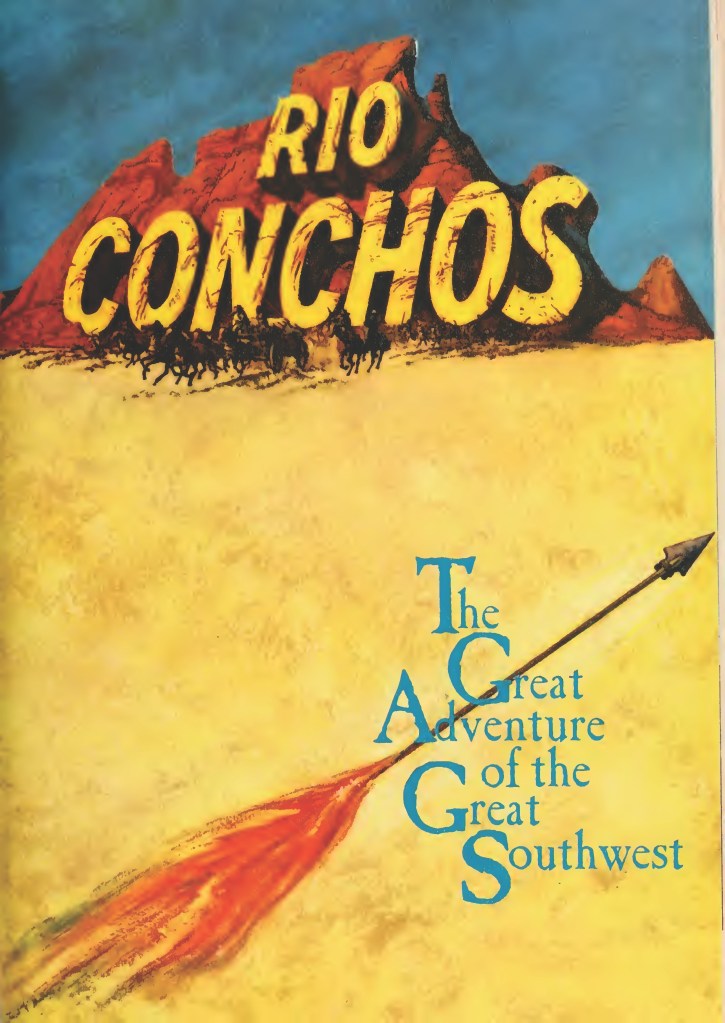

Starts and ends as a rootin’-tootin’ western but sags badly in between. The chance of turning it into The Magnificent Four or even The Dirty Pair go a-begging and it’s both revenge- and redemption-driven without either taking enough precedent. And there’s a curious dynamic in that the murderers are clearly smarter than the soldiers. Set in the aftermath of the Civil War, it’s engaging enough but too episodic and far short of a classic.

Lassiter (Richard Boone) kills Apaches with brutal efficiency in revenge for losing wife and child to them. But there’s no law against murdering Native Americans, not even when they form a harmless burial party, and when arrested by Captain Haven (Stuart Whitman) it’s for buying a stolen rifle, part of a consignment of 2,000 feared to be heading into the hands of the Apaches and a rogue Confederate Col Pardee (Edmond O’Brien), under whom Lassiter once served.

Charged with going undercover to get the weapons back is Haven, who lost the cargo in the first place, and another soldier Franklyn (Jim Brown), posing as gunpowder salesmen. Lassiter is freed from jail along with exceptionally vain murderer Rodriguez (Anthony Franciosca). From captured Apache Sally (Wende Wagner) they discover the Apaches are hooking up three days hence with Pardee in Rio Conchos in Mexico.

Mostly, it’s tension between the soldiers and their captives-turned-colleagues. There’s an incident with a dead baby at a house attacked by Apaches, Lassiter shooting the tortured mother. Lassiter attacks a saloon keeper for refusing to serve Franklyn. Pardee is building an army to re-start the war. There’s a brutal scene of the men being dragged behind horses. While Haven plans to use the gunpowder to blow up the Apaches and/or the rifles, Lassiter and Rodriguez nurture plans to steal the cargo.

Lassiter is pretty smart, twice outwitting the Apaches by using fire as a distracting device, easily getting the better of Haven and more than a match for the duplicitous Rodriguez. But there’s a powder keg waiting to explode in more ways than one, the chances of Lassiter toadying along to Apaches seeming remote.

Richard Boone (Night of the Following Day, 1969) coming off Have Gun –Will Travel (1957-9163) and The Richard Boone Show (1963-1964) is impressive as the wily renegade. Here’s one of those actors you never quite know what he’s going to do and that unpredictability adds continuous tension, but it would probably have helped if the audience was fully filled in on his intentions, rather than being surprised all the time. Given he was the star here, he was allotted time to be seen making up his mind in various situations, something he would be denied as a later supporting actor. So when there’s not really much going, he creates tension.

Stuart Whitman (Sands of the Kalahari, 1965) doesn’t really have enough to do what with Boone’s character always being one step ahead and clearly more attuned to danger. Anthony Franciosca (A Man Could Get Killed, 1966) has a gem of role, adding to his characterization withlittle bits of scene-stealing business, sharpening a knife on a wagon wheel, recovering a knife from the stomach of a victim being dragged away by a horse, snaffling a packet of cigarettes, and never ceasing to admire his attraction to women.

Jim Brown (The Split, 1968) makes a solid movie debut, offering more by his presence than in action terms since for the most part he is just the sidekick. Wende Wagner (Guns of the Magnificent Seven, 1969) has more screen time but mostly just smolders or looks sullen apart from a nice scene mourning the baby and another defying her tribe. Look out for Edmond O’Brien (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, 1962) and silent child actor Warner Anderson.

The action sequences are well done and director Gordon Douglas (Robin and the Seven Hoods, 1964) also deserves credit for allowing Boone such scope while the opening scene and the death of the unseen woman are exceptional. He has a great gift for the widescreen, but the movie could have done with more clarity. It’s not his fault the poster was misleading and led me into the picture with different expectations. The screenplay by Joseph Landon (Von Ryan’s Express, 1965) and Clair Huffaker (The War Wagon, 1967).was based on the latter’s book.