Notable for the debuts of Sarah Miles (Ryan’s Daughter, 1970) and Terence Stamp (The Collector, 1963) and an ending that even in those misogynistic times was wince-inducing. The halcyon era of dull English schoolteachers being celebrated (Goodbye, Mr Chips, 1939) or finding redemption or even just managing to overcome pupil hostility (The Browning Version, 1951) were long gone, replaced by a more realistic view of the casual warfare endemic in education establishments, not quite in The Blackboard Jungle (1956) vein but running it close, with bullying, sexual abuse and ridicule running riot.

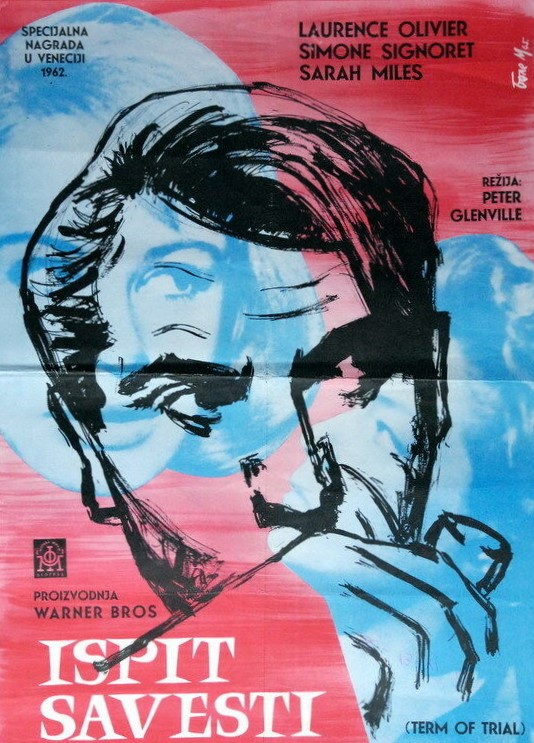

Self-pitying Graham Weir (Laurence Olivier) has failed to achieve his ambitions in part due to alcoholism, in part to antipathy to his conscientious objection during World War Two. And although he has a sexy French wife Anna (Simone Signoret) in the days when any Frenchwoman was deemed a goddess, she is embittered that the future he promised has not materialized. Like To Sir, with Love (1967) his classroom is filled with no-hopers so that he responds to the meek and innocent wishing for educational betterment.

Weir’s only defence against endless indignity is a stiff upper lip and slugs of whisky. His lack of character contrasts with a young lad who takes revenge against constantly being chucked out of his house by his mother’s lover (Derren Nesbitt) by blowing up the man’s sports car.

Spanning the twin cultures of religion and the razor, one falling out of favor, the other holding violent sway, opportunity to rise above kitchen-sink England lies with the self-confident such as thug Mitchell (Terence Stamp) who smokes in class, gives the teachers lip, takes photographs of girls in their underwear in the toilets, physically threatens classmates and when his target is bigger gets older men to give him a good thumping.

A somewhat unlikely development is an end-of-term trip to Paris where the infatuated Shirley (Sarah Miles), who the good-hearted Weir has been giving free private tuition, ends up in the teacher’s bedroom and later accuses him of abuse. The impending court case and threat of imprisonment scupper Weir’s chances of promotion, make him consider suicide, and Anna to leave him.

The court scenes allow a number of famous character actors a moment of acting glory. Laurence Olivier (Bunny Lake Is Missing, 1965) must in part have been attracted to the role by a terrific court monologue. The movie is very downbeat in a country universally known never to enjoy an ounce of sunshine justifying the black-and-white movie rendition. If there is liveliness in the streets, cinemas, shops, it never translates into any of the main adult characters, all determined to uphold ancient values and endure constricted lives.

Exploiting audience expectation for verbal fireworks, the tension in Laurence Olivier’s finely judged performance comes from his untypical, unshowy delivery. You can almost hear him grinding his teeth. Simone Signoret (The Sleeping Car Murder, 1965) also acts against the grain, battening down her inherent sexuality, and her very presence speaks of lost hope, the fact that she was once attracted to Weir indicating he was once a very different prospect.

Sarah Miles excels as the wannabe seducer, that hesitant voice that would become her hallmark, struggling here to turn innocence into lure, expressing her adoration in heart-breaking simplicity, and yet aware that to catch Weir would require more than just the submission a guy like Mitchell requires. While hers is a stunning debut, I’m at a loss to see what marked out Terence Stamp’s typical surly teenager for speedier stardom.

Oscar-winner Hugh Griffiths (The Counterfeit Traitor, 1962) is the pick of the supporting roles. A remarkable scene-stealer, a shift of his head, a flicker of his eyelashes is all he needs while sitting in the background to attract the camera from another character in the foreground. Look out for Barbara Ferris (Interlude, 1968), Derren Nesbit (Where Eagles Dare, 1968), Allan Cuthbertson (The 7th Dawn, 1964), Roland Culver (Thunderball, 1965) and Thora Hird (television’s Last of the Summer Wine, 1986-2003).

Surprisingly un-stagey direction from Peter Glenville (Becket, 1964) who was far better known as a theater director in London and Broadway. Probably in those days if you were setting a movie outside sophisticated London you had to present a gloomy version of Britain so you can’t really blame him for that and Olivier was hardly a major box office attraction so a budget trimmed of color would be a requisite. Although the older characters display grim determination, the younger ones have not had the spirit knocked out of them in the Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) manner and the location shots reveal a buzzy atmosphere.

Glenville also wrote the screenplay based on the bestseller by James Barlow.