Gangsters are just the same as you and I. They want to be loved, they want a family, they want the kind of respect that isn’t achieved by just pointing a gun at someone. The Godfather (1972) led the way in subtly reminding us that gangsters were human beings even if it was more seductive in making us believe we should excuse their criminal tendencies. Lepke spends as long on romance and trying to win the approval of the bride’s father as it does on the character’s perfidy. The idea that marriage cannot so much absolve you of your sins but provide an oasis of calm inside a murderous world is one only a true romantic would consider pursuing. As is the notion that a wife would forgive you your sins because her love would outweigh your actions, in the same way as the wife-beaten wife (as shown in Love Lies Bleeding) still loves her husband no matter how brutal the treatment meted out.

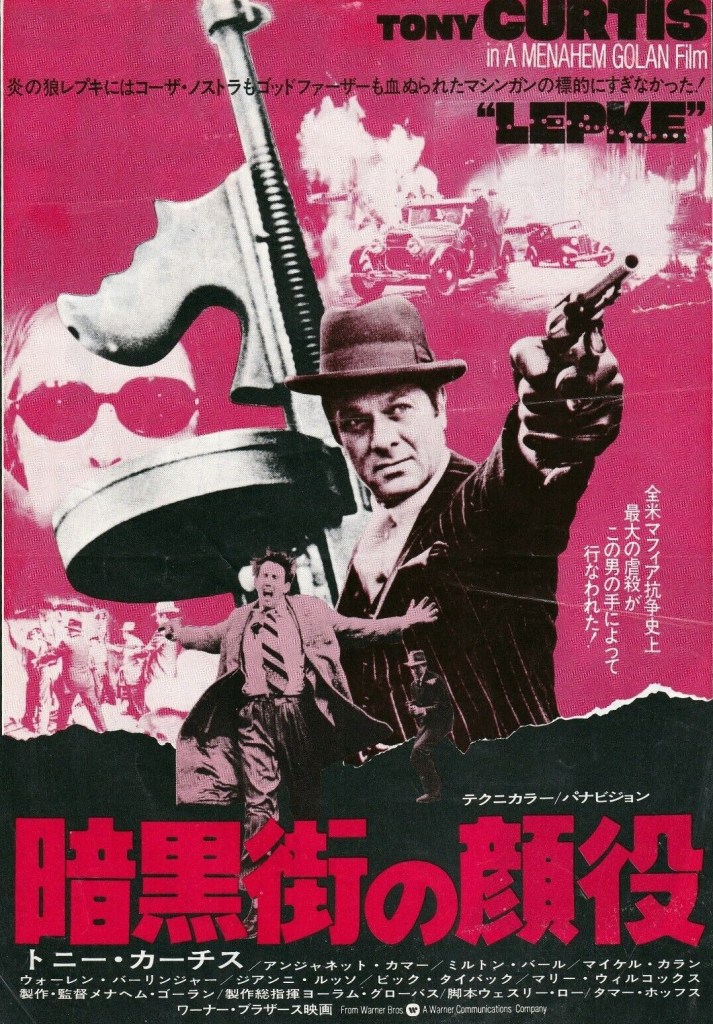

Lepke has got reason to be sore with the world. He was left out of the gangster chronicles. An important part of the Murder Inc operation, he was ignored when Hollywood passed judgement on such criminal enterprises. And you get the sneaky feeling his life story was only revived because after the Coppola epic his was one of the few tales untold in the gangster chronicles.

“If there’s any good in him, that’s the part I’ve got,” says wife Berenice (Anjanette Comer), “If I was a whore I could leave him.” And you can see the part she adores, not only respectful to the point of being obsequious to her upstanding father Mr Meyer (Milton Berle), but charming and romantic with her and he’s clearly able to separate business from romance, turning into an exemplary family man (but then so, too, did Don Corleone).

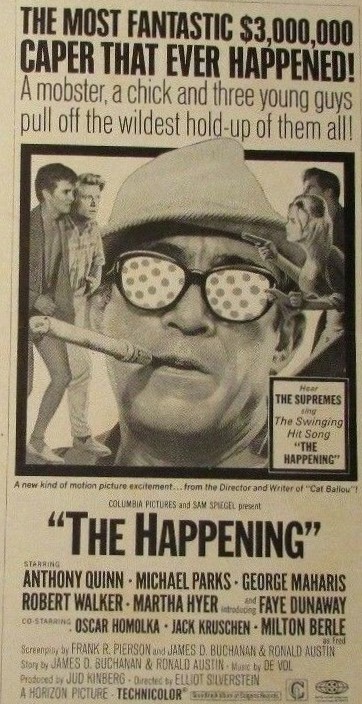

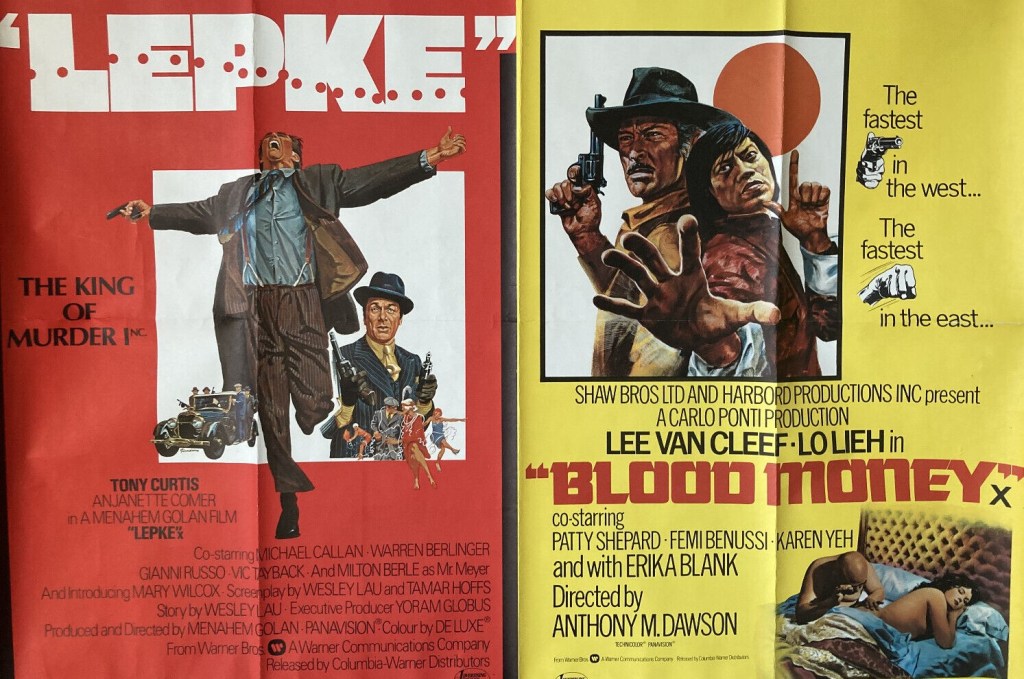

Which is just as well because Lepke (Tony Curtis) is a dreaded Mafia enforcer, forming a murder syndicate with Dutch Schulz (John Durren) and Lucky Luciano (Vic Tayback) that takes responsibility for knocking off anyone who steps out of line away from the big bosses. There’s some standard gangster stuff, machine guns in violin cases, bombs in the spaghetti, but also some interesting touches, a shoot-out on a carousel, and of course the last person a gangster can trust is the one he places his truth with. Double-dealing is the order of the day.

Like all the top gangsters, Lepke is an entrepreneur, expanding out of the killing racket into dope, extortion and trade unions. New York D.A. Thomas E. Dewey is on the Murder Inc case and his assassination is only prevented by the intercession of Lepke. But he’s tackled as much by Robert Kane (Michael Callan), friend to Berenice who works in narcotics along with Dewey.

Dewey’s not the only real-life character making an entrance. Legendary journalist Walter Winchell (Vaughn Meader) plays a significant role. Most of the picture involves Lepke being nefarious by day and loving at night and the gang are only tripped up when witnesses need to be eliminated and as the cops work a similar kind of dodge to the one that snared Al Capone. Instead of tax evasion it’s anti-trust issues.

Covering the period from 1923, Lepke’s emergence as a ruthless street rat, and his development of the narcotics business by sourcing product direct for the Far East, to his execution in 1944, it pays only cursory attention to the period. Most of the time, Lepke is fighting for his life one way or other, suspicious of colleagues, walking a knife-edge between actions that could inavertently lead to his demise, and trying to remain the best part of himself that remains appealing to his wife.

That any of this works other than being a standard depiction of the rise and fall of a gangster is down to Tony Curtis (The Boston Strangler, 1968) who delivers one of his best later performances while maintaining a difficult balancing act, clearly believing that he can separate the two sides of his personality, and that the murderous part is really just a performance. The documentary-style rendition helps as this can be complicated stuff, especially with so many disparate traitors.

Anjanette Comer (Guns for San Sebastian, 1968) is always watchable. Menahem Golan, of Golan-Globus and Cannon fame, perhaps taking a cue from The Godfather, takes considerable care with the family elements and is rewarded with a better picture than the elements might suggest.

This pretty much rounds out my Hollywood History of the Gangster.