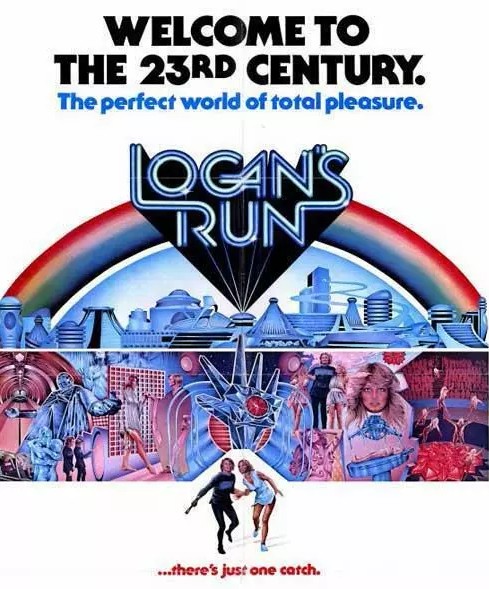

Shortly after this appeared the movie sci fi world imploded/exploded with the release of Star Wars (1977), followed by Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Alien (1979), which probably accounts for why this is such a throwback joy to watch and now very much a cult item. Takes in ageism, obsession with youth, death cult, the pleasure principle written in capital letters, some kind of primitive Tinder (where women place themselves on “the circuit”), Terminators, runaways, dystopia, escapees, eco-friendly food, mobile phones, computers in charge, lasers, plastic surgery, cannibalism, robots, an icy tomb, nuclear holocaust and the Lincoln Memorial.

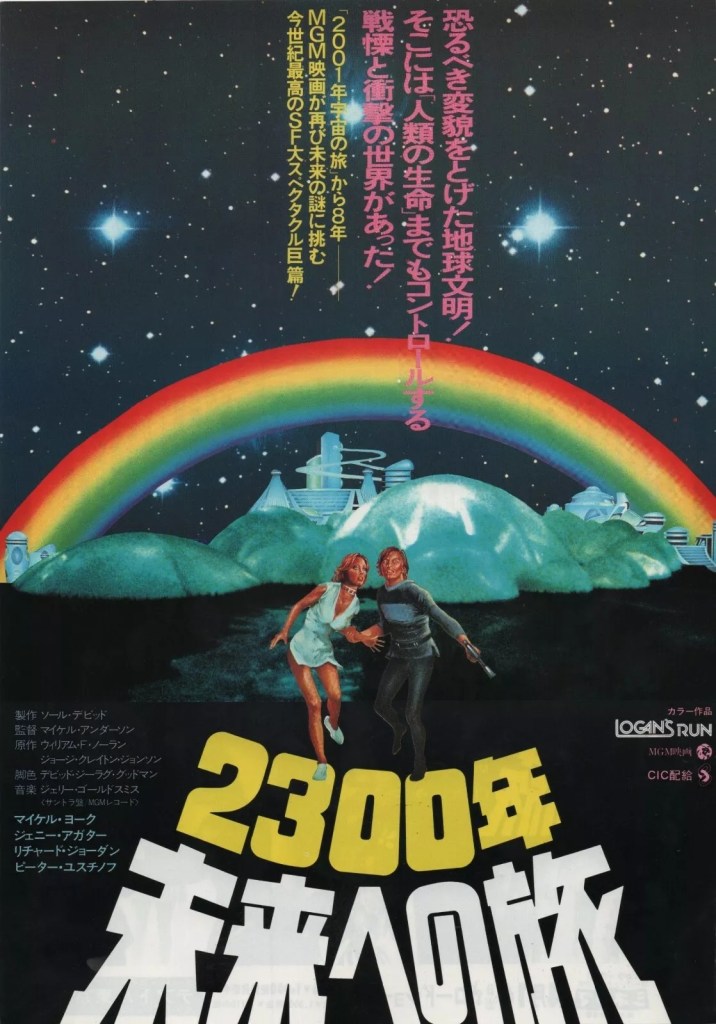

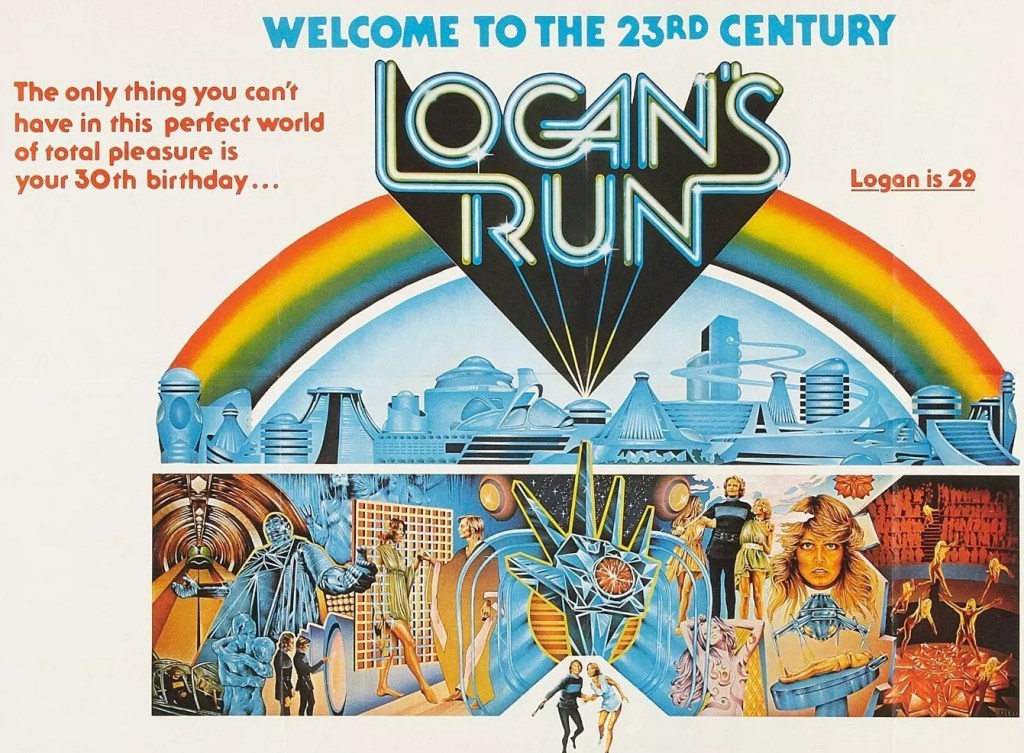

There’s some shooting with futuristic weaponry but these handguns are virtually useless given how poor their accuracy – though that may be down to the incompetence of their users – and a couple of fist fights. And while the remainder of Earth’s population enjoys an idyllic life in a series of sealed domes, there is, as the posters point out, a catch. When you reach the age of 30 you are killed, although this occurs in the guise of rebirth in a ritual known as the Carrousel.

There’s no individual responsibility. Children are separated at birth from their parents and brought up in communal fashion. They eat, drink and have sex – there’s even a section set aside for sexual pleasure, full of naked writhing bodies. But generally, sex is on tap, any woman signing up to be on “the circuit” literally delivered to your door.

In this fashion Logan 5 (Michael York) encounters Jessica 6 (Jenny Agutter). He’s a terminator, chasing after runaways, she’s a virgin and much to his annoyance proves not an easy conquest, in fact sex doesn’t take place at all. However, she wears an ankh. And he’s just picked up an ankh from a runaway he just totaled. So he asks the computer for advice about the emblem. Turns out it’s worn by a rebel group – there are over 1,000 of them living in a “sanctuary” in the city – and Logan is delegated to pretend to be a runaway and with Jessica’s help infiltrate the radical organization. Unfortunately, his buddy Francis 7 (Richard Jordan) is suspicious and follows him.

After many adventures and escaping from Francis and the robot Box (voiced by Roscoe Lee Brown) who wants to freeze them, they emerge into a land that while it shows signs of devastation is not uninhabitable. They meet an old man (Peter Ustinov) and realize that it’s possible to live beyond the age of 30 and that somehow their apparent utopia is actually a dystopia. Furthermore, once outside the tomb, the internal clocks that dictate the date of their death automatically switch themselves off.

The prisoners of the dome are freed shortly afterwards.

There’s a kind of innocence about the sci fi world portrayed. Everyone dresses in primary colors, both sexes wear flimsy outfits all the easier to remove when pleasure appears imminent. Taking place three centuries on from the date of the movie’s release, the world is the kind that would be dreamed by illustrators imagining the future for an Exposition with everything streamlined.

There’s no time and really no effort to make a serious point about any of the issues raised and it’s more a smorgasbord of ideas – quite a few of which have come to fruition. The two main characters are likeable rather than charismatic and the onset of sudden romance appears narrative contrivance rather than “across a crowded room.” Logan’s dilemma, that he is switched from having four years to live to being at death’s door, gives him incentive to escape, not to complete his mission. And at times the dialog is cumbersome but equally often just flies – that cats have three names, for example.

I never saw this on initial release and didn’t hire it on VHS or DVD but gradually it acquired cult status and I was keen to see why.

It works, is the real reason for that. It exists outside the Star Wars/Close Encounters/Alien dynamic. I liked the jigsaw nature of the ideas and that they are thrown together and at you like you were on a rollercoaster, and you can pick and mix. The conversations with the computer sound very contemporary.

Michael York (Justine, 1969) and Jenny Agutter (East of Sudan, 1964) are pleasant company to spend time with. While Richard Jordan (Valdez Is Coming, 1971) is not much short of an eye-rolling villain, Peter Ustinov is remarkably good value in a role that could easily have been cliché. You might spot Farrah Fawcett-Major (newly-inducted as one of Charlie’s Angels, 1976-1980).

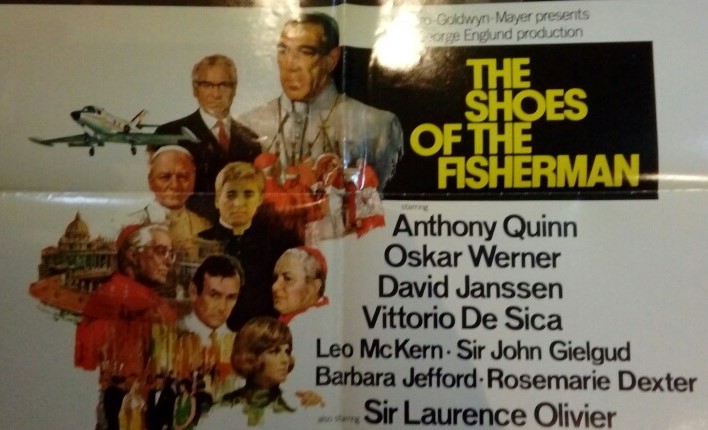

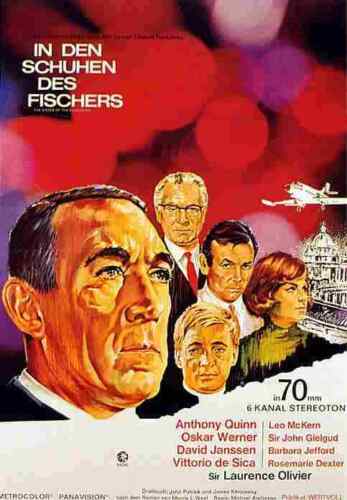

Directed by Michael Anderson (The Shoes of the Fisherman, 1968) and written by David Zelag Goodman (Straw Dogs, 1971) from the novel by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson.

Any notion that it was intended to be groundbreaking was knocked on is head by Star Wars et al, and it’s for that very fact that it’s so watchable, as in, the direction sci fi could have gone had lightsabers and Death Stars, creatures phoning home and monsters erupting from stomachs, not entered the Hollywood universe.

Surprised how much I enjoyed it.