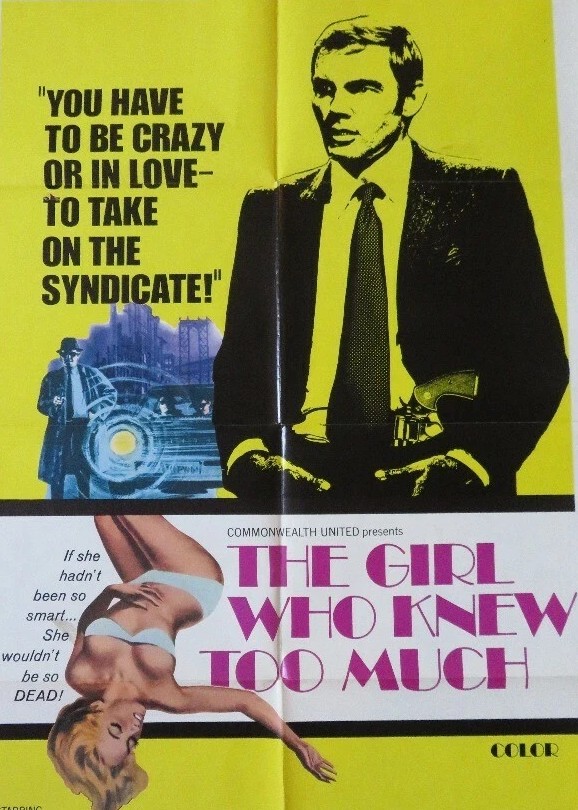

Prophetic plot is the best reason to watch this more considered feature from newcomers Commonwealth United. Another movie featuring a former star on the wane in Nancy Kwan. Again, one of those neo noir films which might have made a bigger splash with an actor other than Adam West, coming off the Batman television series and 1966 film, in the lead. A fair bit of philosophizing from the supporting cast.

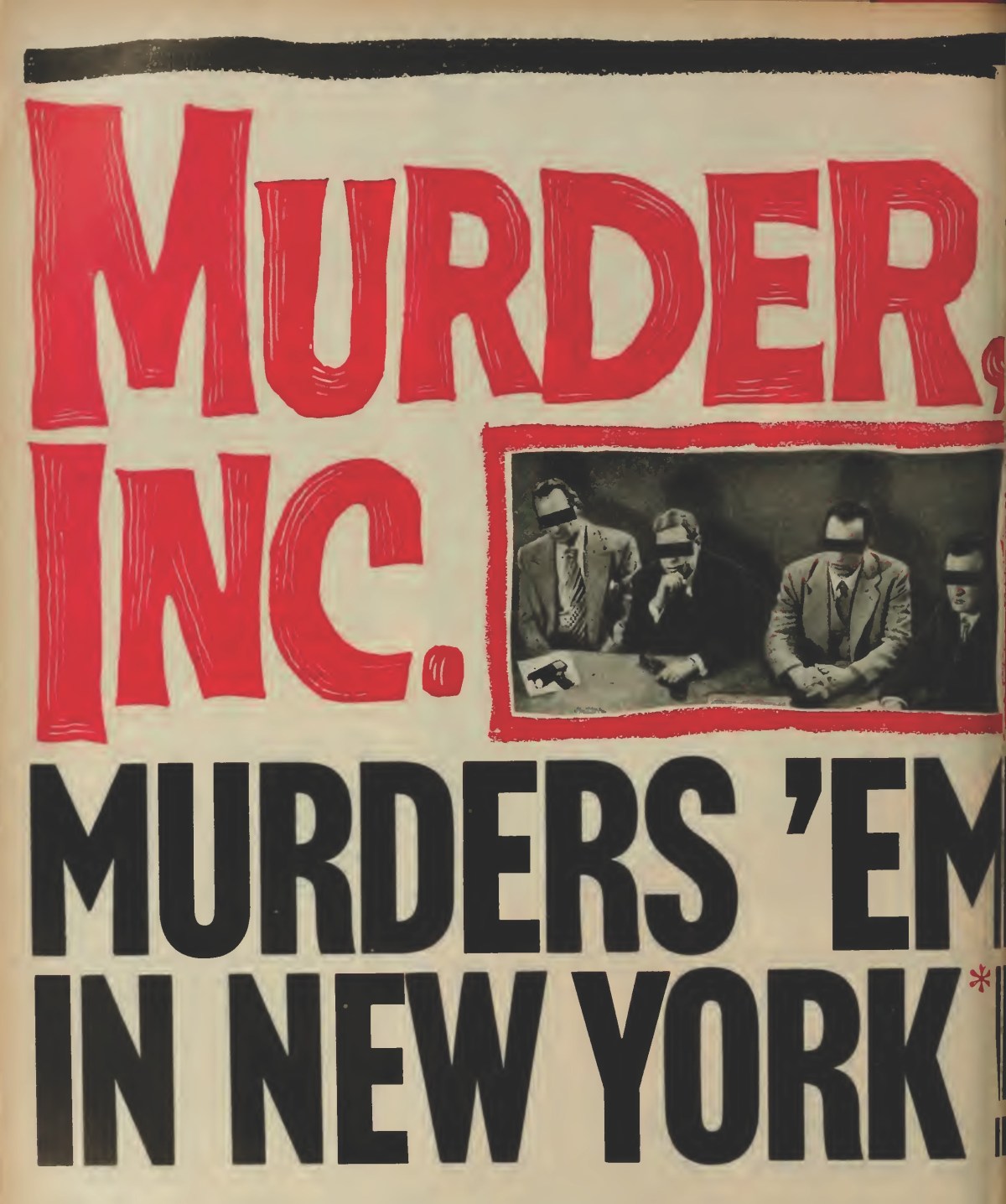

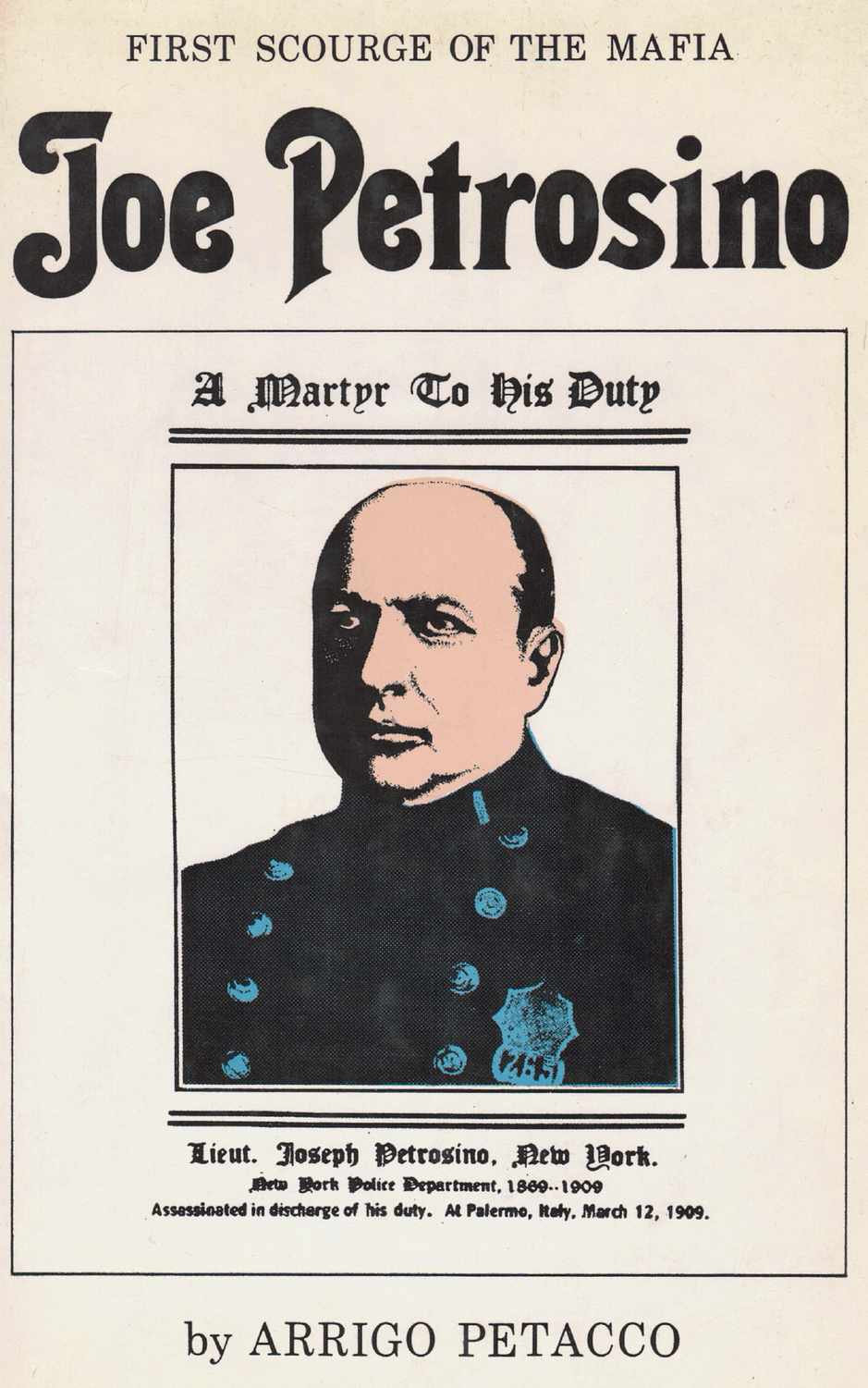

The Mafia trying to go legit had been tackled in Point Blank (1967) and The Brotherhood (1968) and would be key to Michael Corleone’s machinations in The Godfather Part Two (1974), but here it goes into far deeper and more dangerous territory. At this point, organized crime was still run by the Mafia, but what if that and the legitimate big businesses and financial institutions they operated were prey to foreign interests.

Most movies that involve Russian, Eastern European, Albanian or South American gangs taking over American criminal networks, usually by force, concentrate on the illegal activities rather than the legitimate and powerful businesses suborned through money laundering. Although here the plot is somewhat convoluted involving the CIA and priceless artefacts, the core asks the question – what would happen in the U.S. should the Mafia come under Far East control.

This occurs for the dumbest of reasons. One of the Mafia top hoods, part of the management committee, wants to be in sole control so he’s enlisted the help of Far Eastern bodies, not realizing that the foreigners intend it to go the other way, and that he is in their grasp.

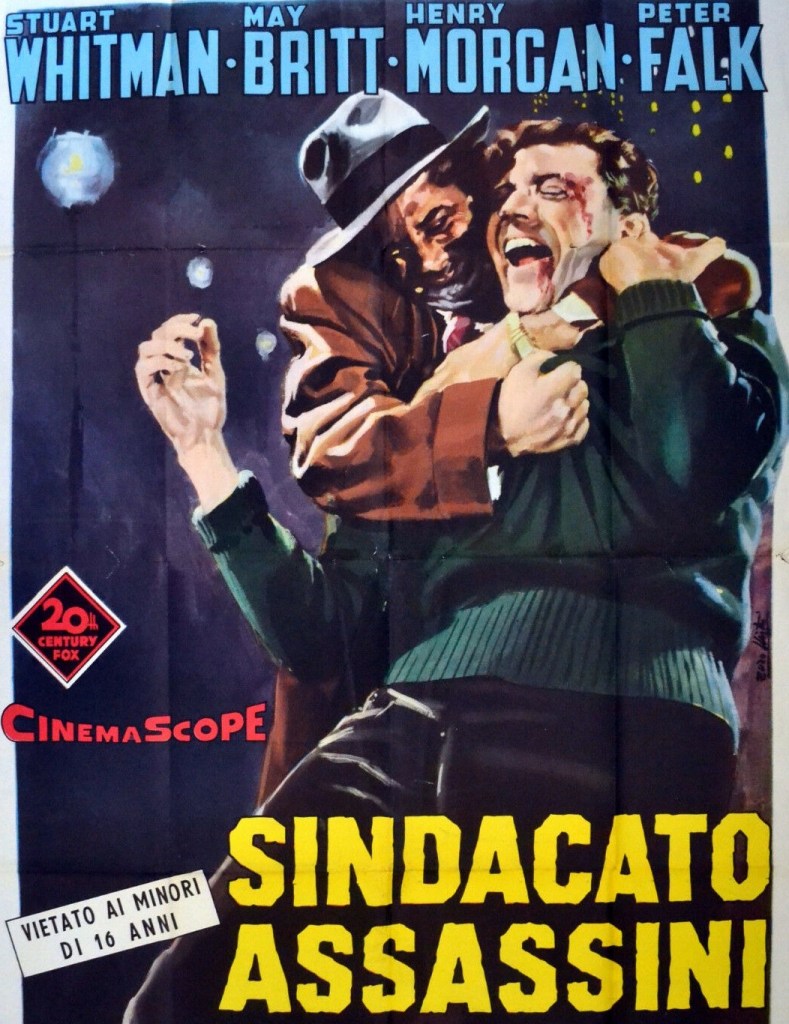

A convoluted tale is an invitation to plot holes. Hard to imagine restaurateur Johnny Cain (Adam West) as a former top assassin when in three out of four tussles with gangsters he comes off worst. He’s tossed in the drink, chucked through a window and thrown out of a door.

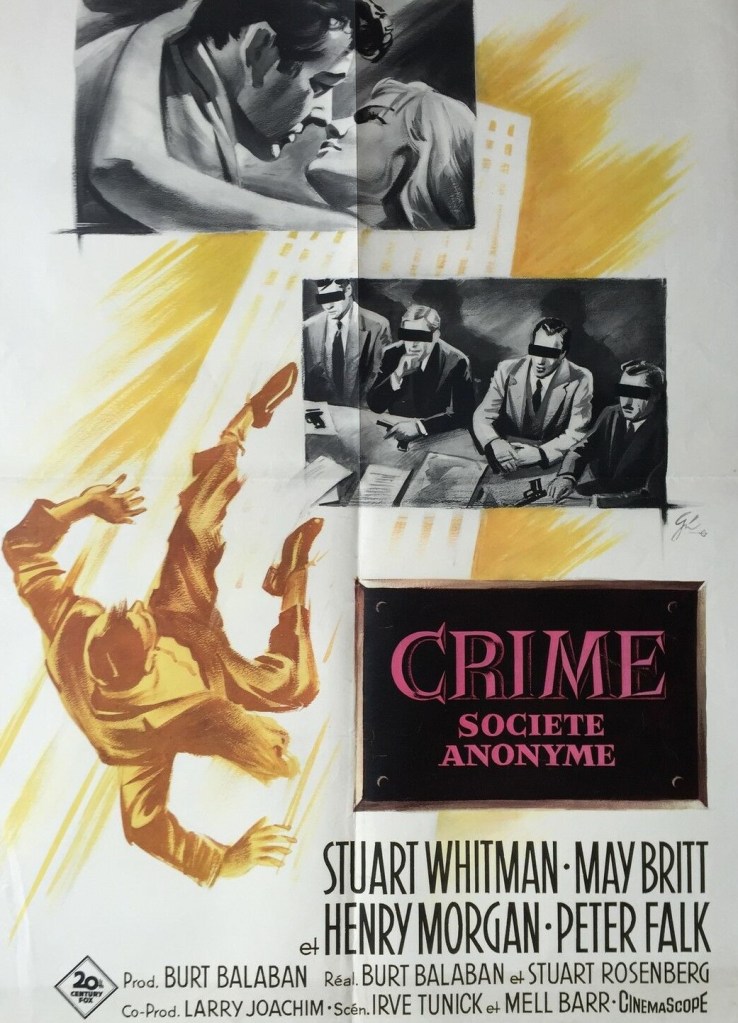

And he’s only turned detective under duress. The Mafia force him to track down the killer of old-school gangster Tony Grinaldi (Steve Peck) otherwise they will take out a contract on him. His first port of call in Grinaldi’s girlfriend Revel Drue (Nancy Kwan), who had enjoyed a brief liaison with Johnny until her lover promised her a termination. Then old buddy Lt Miles Crawford (Nehemian Persoff), philosophizing cop, lends a hand. The CIA turn up the heat since someone is killing the great spies of Bermuda. The missing artefact, a solid gold statue of a Tibetan god, enters the mix. Grinaldi’s wife, drunken actress Tricia (Patricia Smith) is the secret lover of one of the top Mafia guys, Kenneth Allardice (Robert Alda).

When one set of thugs aren’t trying to do away with Johnny, another bunch have Revel in their sights. But it turns out that the foreigners are backing Allardice, knocking off the other four members of his committee leaving him in sole control.

All the way through except clinging to Johnny and looking scared, Revel (“a small town girl who wanted a big city man”) hasn’t had much to do, so I was expecting at the very least, once she turned the romantic screws on Johnny, that she would turn out to be a femme fatale in the pay of the foreigners. Turns out the femme fatale comes from a different source. Tricia has infiltrated the organization, either on her own account or on behalf of the government (it isn’t clear which). Marrying Grinaldi then launching into an affair with Allardice who, having conveniently got rid of his rivals, leaves her in pole position to head the group.

There are some neat touches. Johnny lives on a big yacht not the usual down-at-heel houseboat occupied by a down-on-his-luck private eye, a naked leg part of a naked body warming Johnny’s bed kicks over the phone when it interrupts her bed warming activities, the Mafia headquarters are atop a snazzy department store, the academic Johnny seeks out for information on the artefact is a part-time stripper.

But we’ve also got to suffer two whole songs from cabaret artists Lucky (Buddy Greco) which slows the tempo right down.

Nancy Kwan made an instant splash as the romantic lead opposite William Holden in The World of Suzie Wong (1960), a box office smash, for which she won two Golden Globes. Her star potential was quickly recognized, either top-billed or leading lady in her next seven films. But after Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. (1966) her marquee slipped and after making up the numbers in The Wrecking Crew (1968) her career never recovered. For sure, she held onto her place in the sun for far longer than Tippi Hedren (Tiger by the Tail, 1968) who was at one point the bigger star, but Hollywood burned through stars at a heck of a pace or dropped them altogether or sent them into the exploitation/B-picture hinterland – Kwan was the star after all of Wonder Women (1974) and Fortress in the Sun (1975).

Adam West barely found a place in the sun, five films, and supporting roles/bit parts at that, over the next decade represented a poor return.

Final film of director Francis D. Lyons (Destination Inner Space, 1966), an Oscar-winning editor, from a screenplay by Charles A. Wallace (Tiger by the Tail, 1968). Became something of a cult item on television.

Interesting concept but you need patience.