Minor British B-picture gem, though more for the exquisite narrative and tsunami of twists than the acting. And while not being one of those devious arthouse farragoes spins the starting point as the climax. Also, very prescient, heavily reliant of the espionage tradecraft that would later become de rigeur.

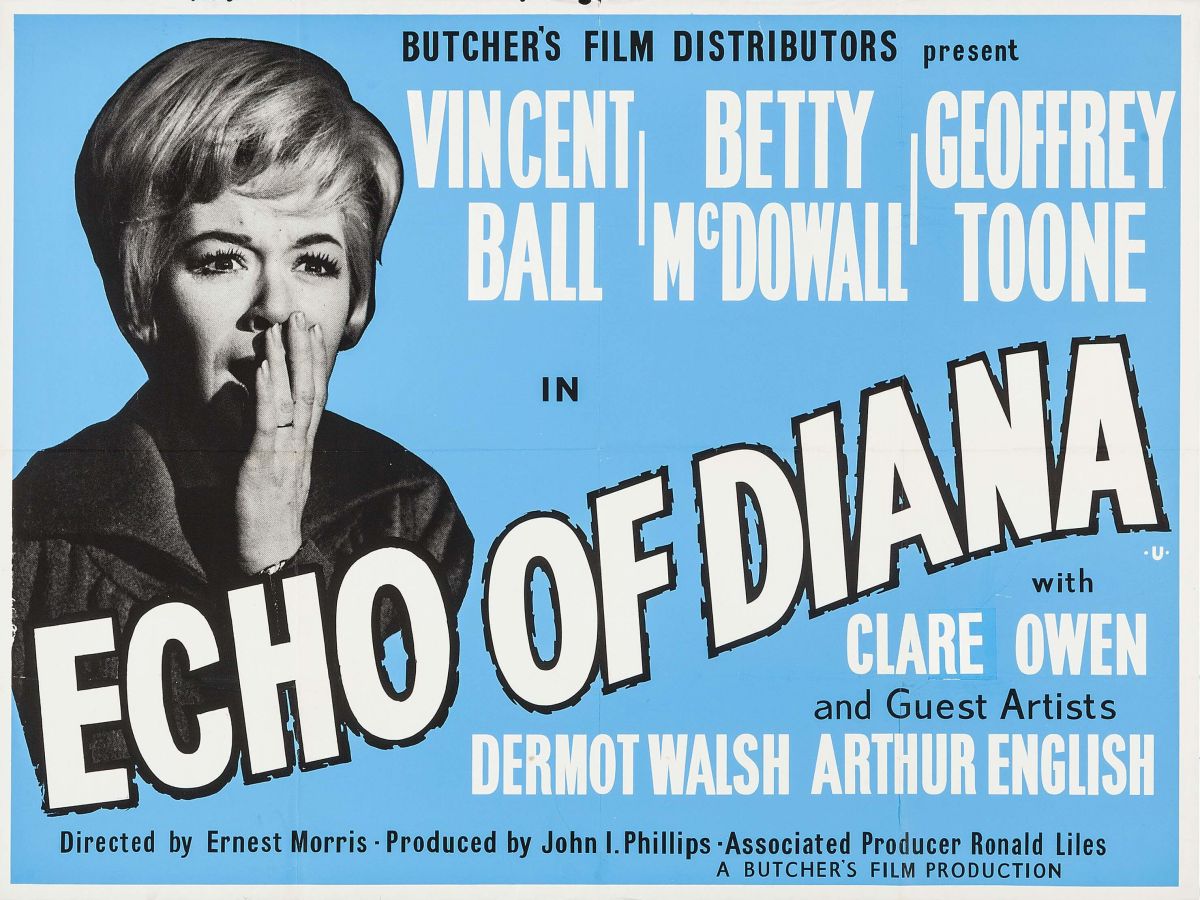

On the day she learns of her husband’s death in a plane crash in Turkey, Joan (Betty McDowall) finds an intriguing reference to the dead man in the “Personal Column” of The Times newspaper signed by “Diana.” Suspecting a mistress or skulduggery, her friend Pam (Clare Owen), a former fashion editor, investigates and triggers trouble. Joan’s flat is burgled, they are accosted by dubious police, the dead man’s effects are foreign to Joan, the receptionist at a newspaper makes a mysterious phone call.

Fairly quickly, Joan and Pam fall in the purlieu of British espionage chief Col Justin (Geoffrey Toone) who puts them in touch with suave journalist Bill (Vincent Ball), an old colleague of the husband, whose apartment has also been tossed, and who has taken a shine to Pam. The women are somewhat surprised when a murder is hushed up but that’s the least of the espionage malarkey. Mysterious contacts, equally odd points of contact, disguises (though mostly this runs to a blonde wig), code names, double agents, phone tapping and mail drops leave the women somewhat befuddled but they play along and with that British bluffness, not quite aware they are acting as decoys to draw out a crew of foreign spies headed by a rough fella called Harris (Basil Beale).

Halfway through it seems her husband might not be dead after all, but, according to the Turkish ambassador, Joan might need to head off to Turkey or thereabouts and certainly other interested parties want her out of the country.

And it being British, and nobody wanting to take the whole thing seriously, especially since the James Bond boom had not begun in earnest, the drama is offset by some pointed comedy: the proprietor of an accommodation address business has a side hustle in porn mags, one of the contacts is annoyingly punctilious, one promising lead turns out to be a very grumpy old man, another lead results in a race horse called Diana in a grubby betting shop where they are rooked by another old guy.

But it’s lavished with twists: double-crossers double-crossed, misleading clues, bad guys far cleverer than good guys, the wrong person in the right car, kidnap, unexpected occurrence. Pretty contemporary, too, with much of the action driven by telephone calls. But something of an ironic climax, the notice in the newspaper having legitimate espionage purpose.

The action is so pell-mell, Joan and Pam scarcely have time to draw breath, never mind give vent to heavy emotion, the best we are afforded is a moment when Joan doesn’t know “whether she’s wife or widow.” But that’s just as well. We are in B-movie land with a B-movie class of actors, probably recognizable to audiences then as the kind of actors who never managed a step up.

Vincent Ball did best, a long-running role in BBC TV series Compact (1962-1965), male lead in skin flick Not Tonight, Darling (1971) and decades of bit parts. You might have caught Betty McDowell in First Men in the Moon (1964) or The Omen (1976). Clare Owen was female lead in Shadow of Fear (1963) and had a part in ITV soap Crossroads (1965-1972).

Directed by Ernest Morris (Shadow of Fear) from a script by Reginald Hearne (Serena, 1962). You’d say a better script than a movie, and with better casting might have taken off, but, still, very satisfying supporting feature for the times.