Funny how you remember the circumstances of seeing a film for the first time. This was important for me because it was the start of me digging into the vast heritage of the movies rather than watching just what was showing at my local cinema. I can’t pin down the exact date, but I have a feeling I was still at school, though in the advanced stage of that academia. I saw this on a 16mm print in a terraced house sitting on the hard kind of seats you used to get in assembly halls.

The location was the Scottish Film Council, the predecessor of the Glasgow Film Theatre, which was located in the city’s West End. The occasion was the final film in an eight-movie retrospective of Elia Kazan pictures. Either before or after I attended a similar Fellini retrospective. Certain more controversial films were omitted, so no Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), Pinky (1948) or Baby Doll (1956) and although this was the early 1970s no room for Splendor in the Grass (1961), America, America (1963) or The Arrangement (1969). Afterwards, there was a cup of tea and a biscuit and a discussion hosted by John Brown, who in my memory smoked small cigars, later a television and screen writer.

It was an introduction for me to the power of the retrospective, to view a huge number of a director’s films back-to-back (the screenings were weekly) and to understand the thematic symmetry of their work. Kazan predated the New Hollywood of the late 1960s and 1970s, so, although his movies usually challenged existing norms, these days they are often viewed as more stolid than of the first rank, his cause not helped by revelations that he named names at the anti-Communist hearings of the 1950s.

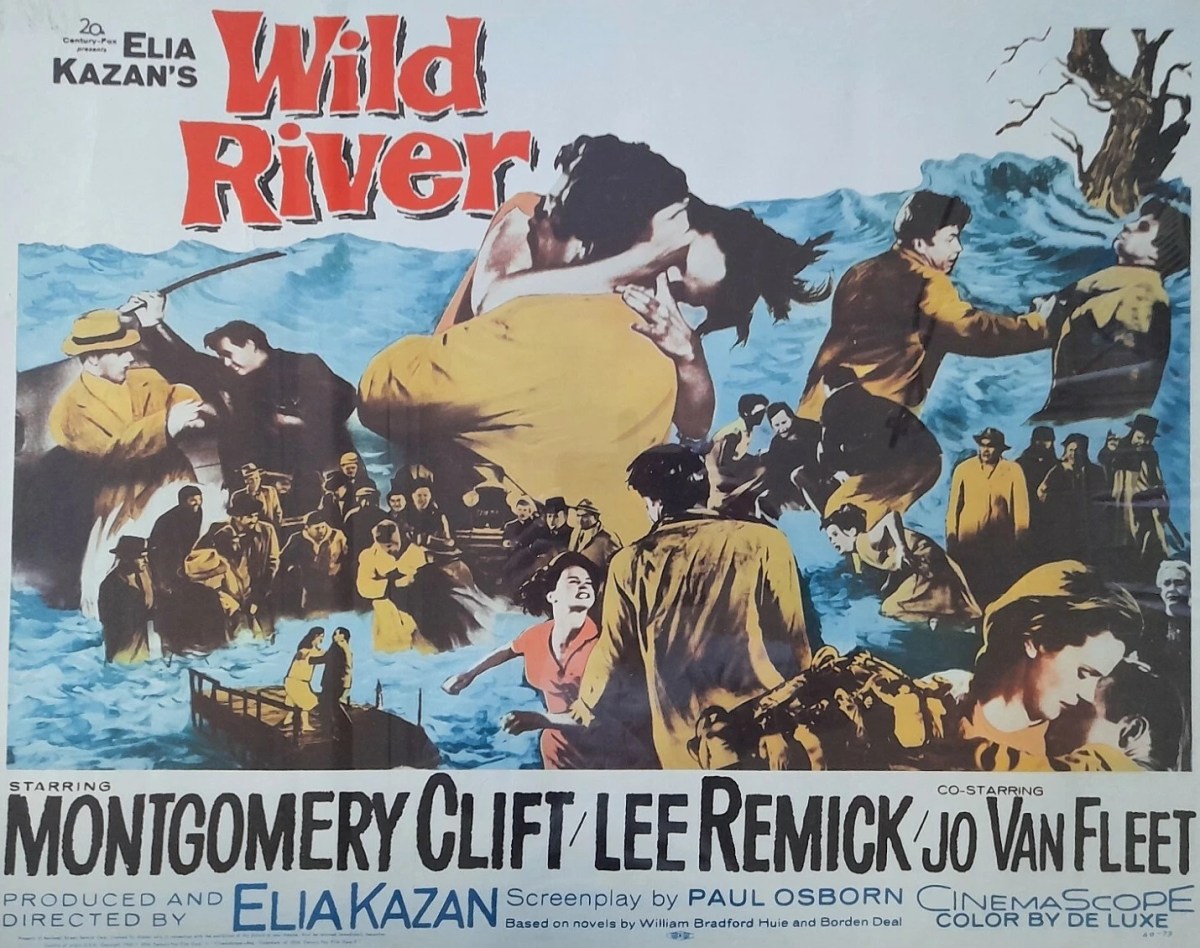

Wild River is one of those films that plays completely differently now thanks to the intervening decades. A contemporary audience is unlikely to sympathize with hero Chuck Glover (Montgomery Clift) whose job is to persuade farmers in the early 1930s to clear out of the way of land that is going to be swamped with water to supply a new dam that would serve to both control the catastrophic flooding in the Tennessee Valley and bring electricity to an impoverished area.

These days ageing landowner Ella Garth (Jo Van Fleet) would attract massive publicity in her fight to avoid being shifted from land that had been in her family for generations, especially as she claims that dams go “against nature.”. And no matter how sympathetic a character like Chuck might be to her circumstances he would be viewed as a more well-meaning-than-most government apparatchik.

And in some respects, this plays much better as one of the few movies exploring the plight of the African American at the hands of the racist authorities. Chuck incites local hostility when he recruits Blacks to work alongside Whites, in the end conceding that they should work in separate crews. But he comes unstuck when he sticks to the principle that they should be paid the same, more than double the going daily rate for Blacks.

In consequence he is beaten up and, worse, a gang of thugs attack the house inhabited by his lover Carol (Lee Remick) and her two young children and the cops, when they arrive, are apt to condone the violence.

Ella takes a maternal attitude to her Black workforce and while certainly nobody received abusive treatment at her hands she has a patronizing manner, though in the end she encourages them to leave.

Despite his democratic and anti-racist views, Chuck comes over as a clever dick, thinking his smooth eastern charm can convince the reluctant woman to move and for the racists to abandon their inherent racism.

I’m not sure about the widowed Carol either, she almost seems to be throwing herself at the first decent man who comes her way. While she is already being courted by a local fellow, who is more decent than the rest, that is clearly going to be a marriage of convenience, but what exactly makes Chuck so much more an attractive proposition is never made entirely clear except that, for narrative purposes, it creates a romantic deadline – is she just a fling, thrown over when he heads home – and a whiff of tension.

However, marriage to the other man would have made her just a passive housewife, whereas she realizes that in many ways she is smarter than Chuck, more grounded, and she would have more freedom in this kind of match.

Oddly enough, there’s a Hitchcock vibe here. At several points the camera tracks Glover in longshot as he appears to be heading for trouble.

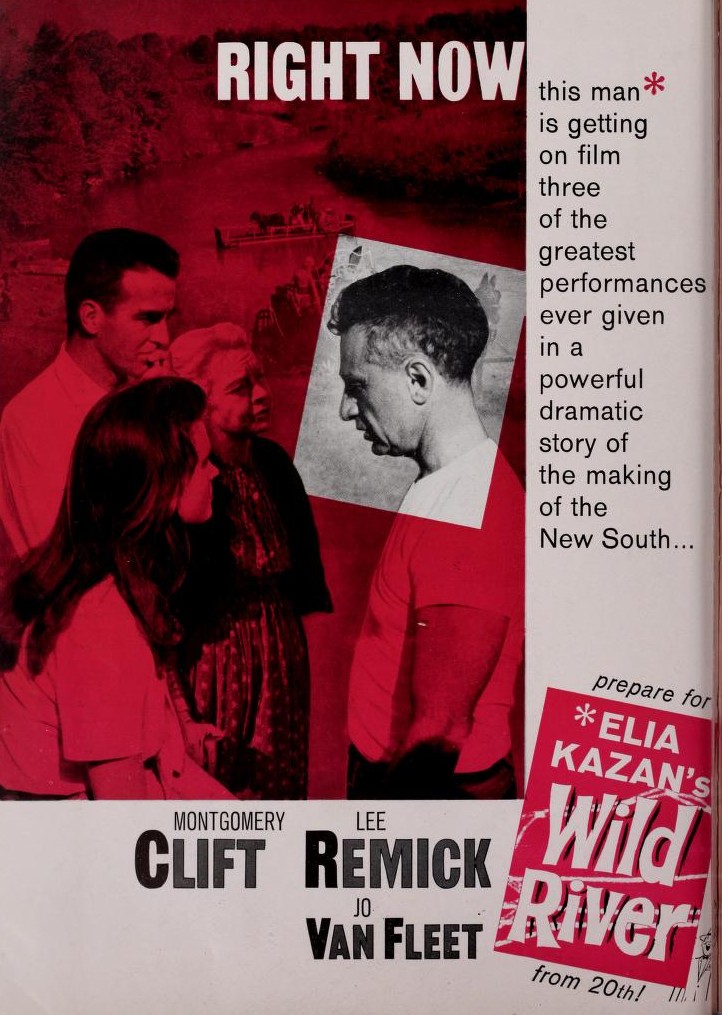

The racist elements give this its bite rather than any ecological issues. The acting is certainly of high quality, Montgomery Clift (The Misfits, 1961), less mannered than in some of his work, in one of his last great roles. It’s an interesting part. At one point he wishes he could once in a while win a physical fight, and it’s Carol who is more likely to show the venom required in battle.

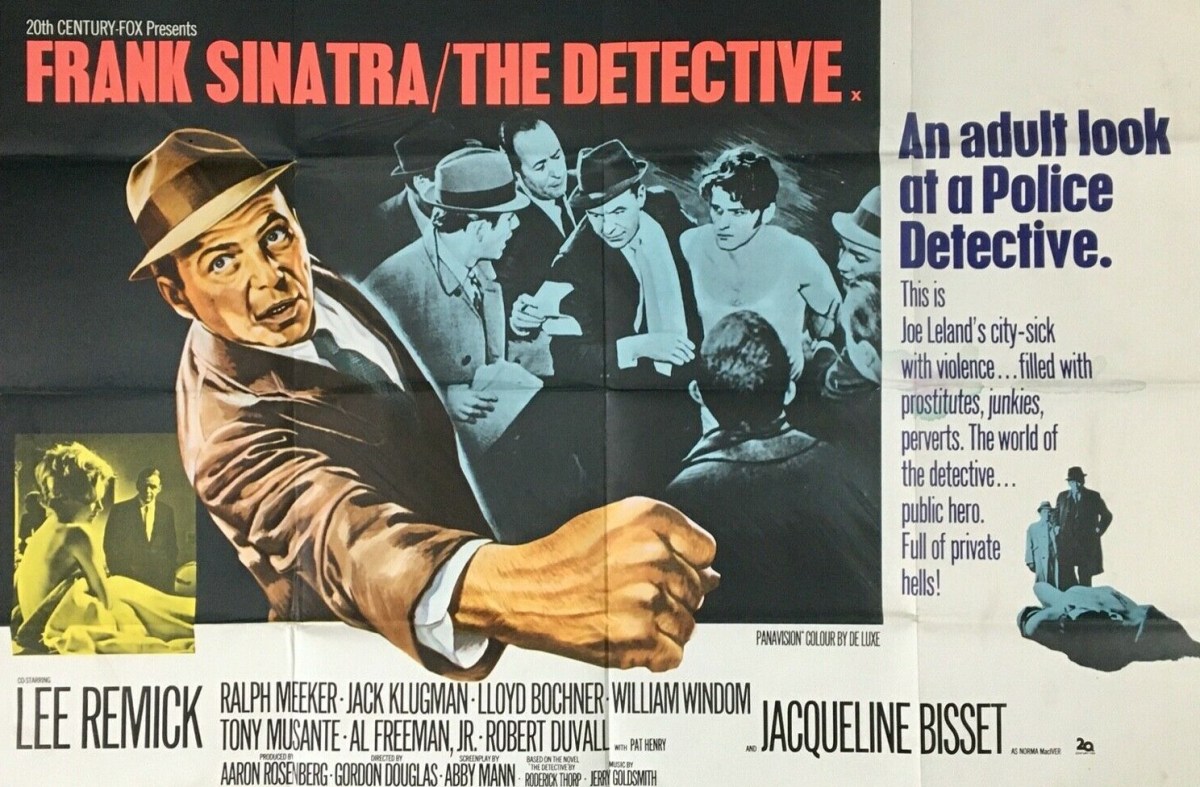

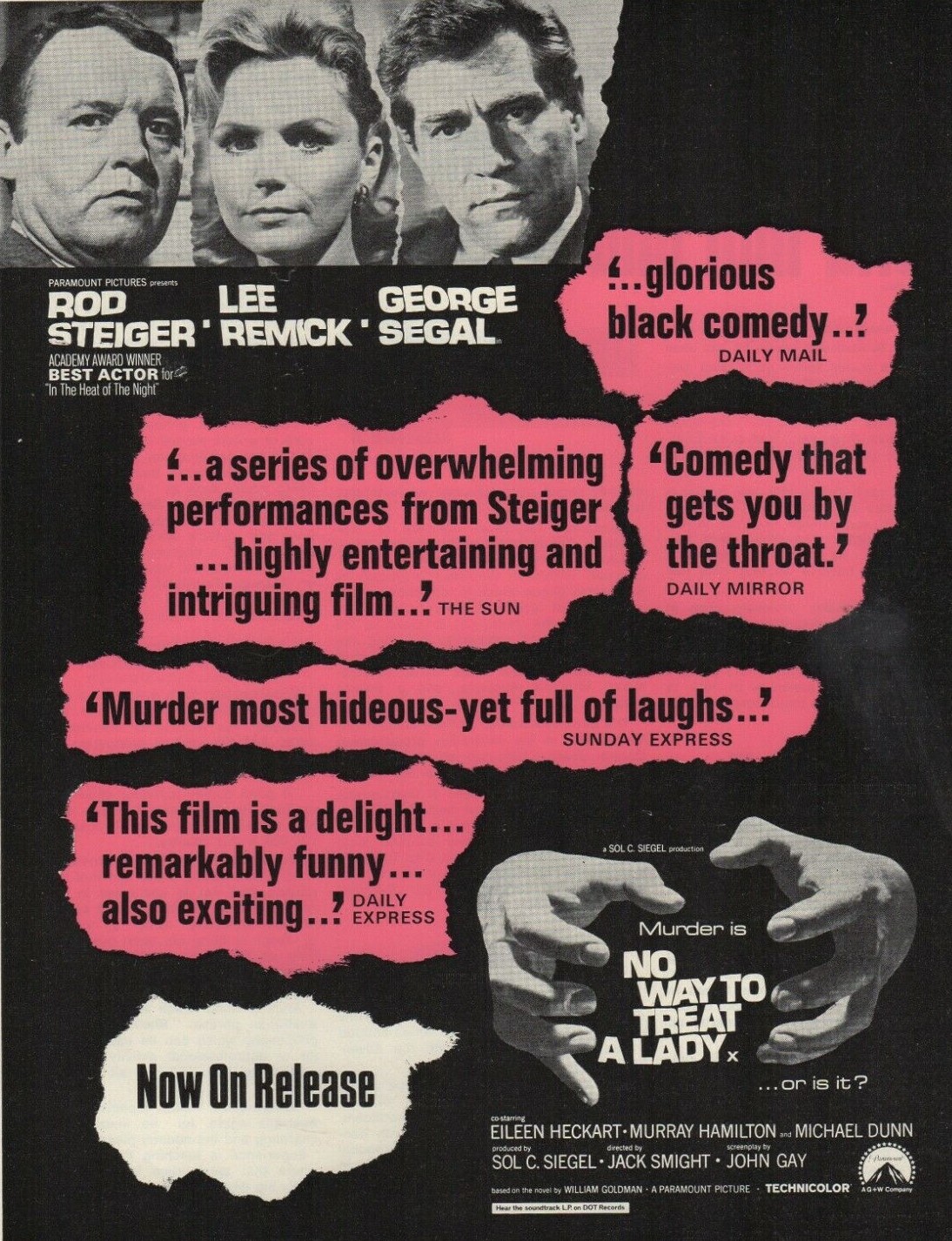

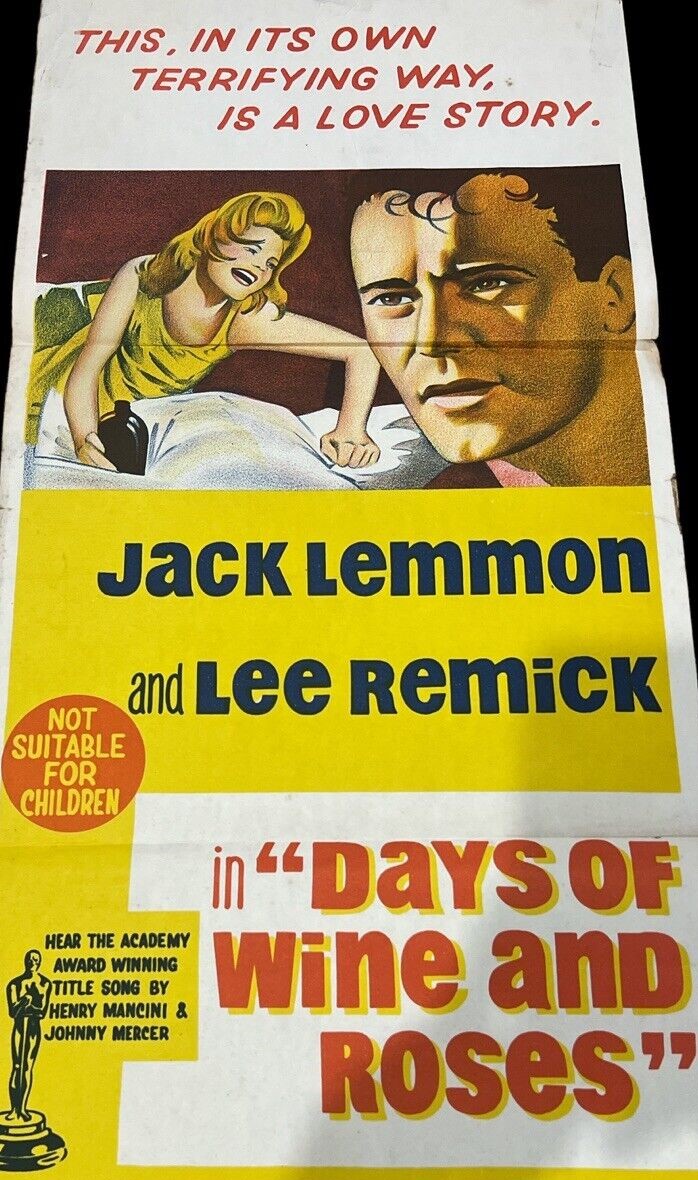

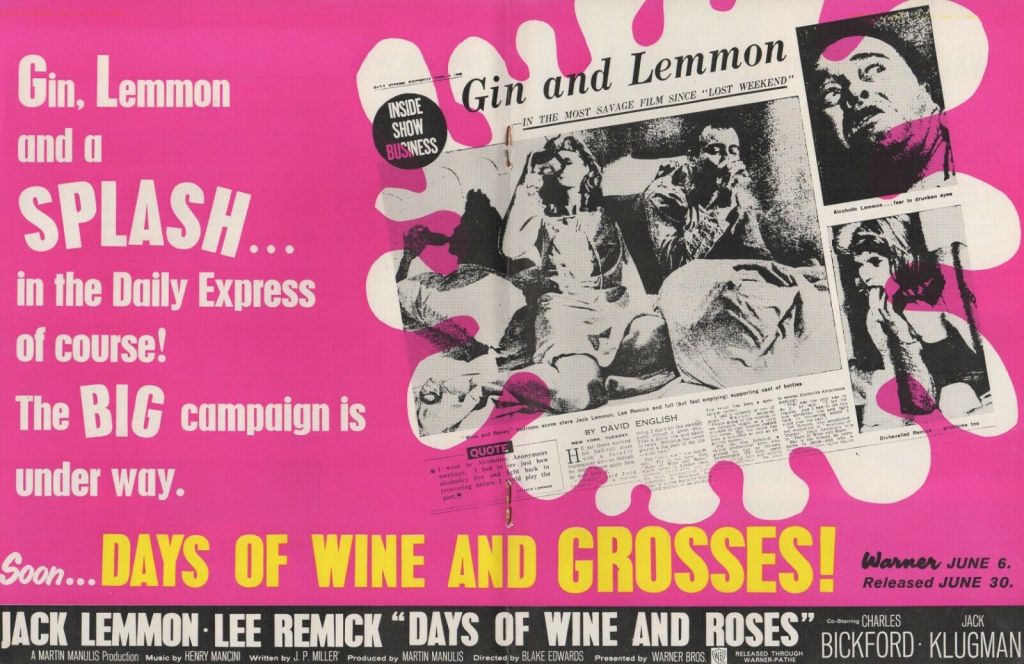

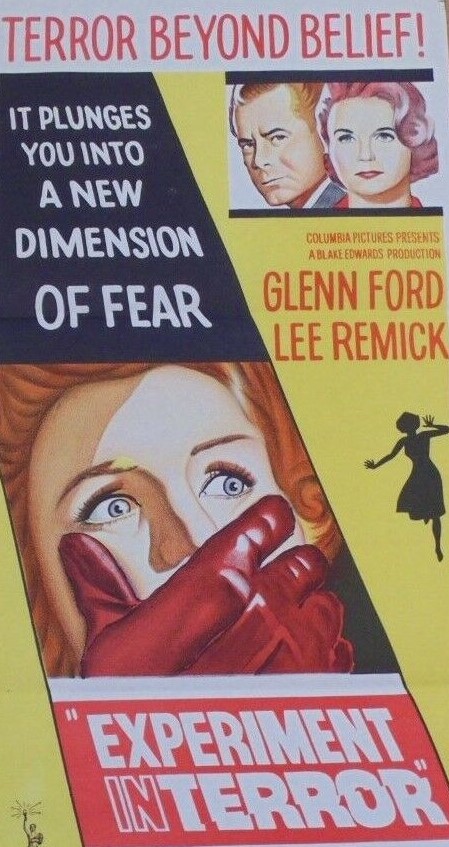

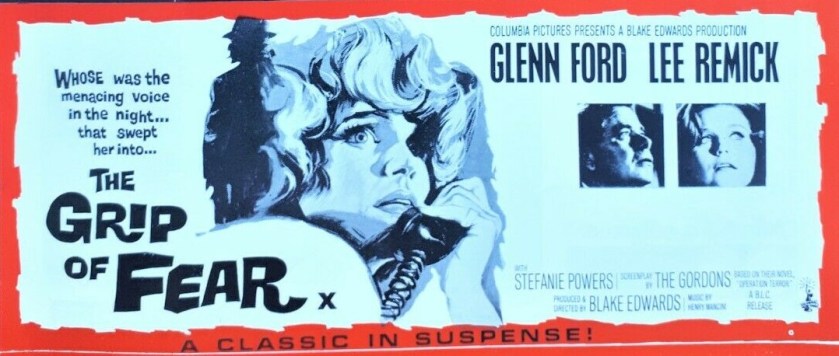

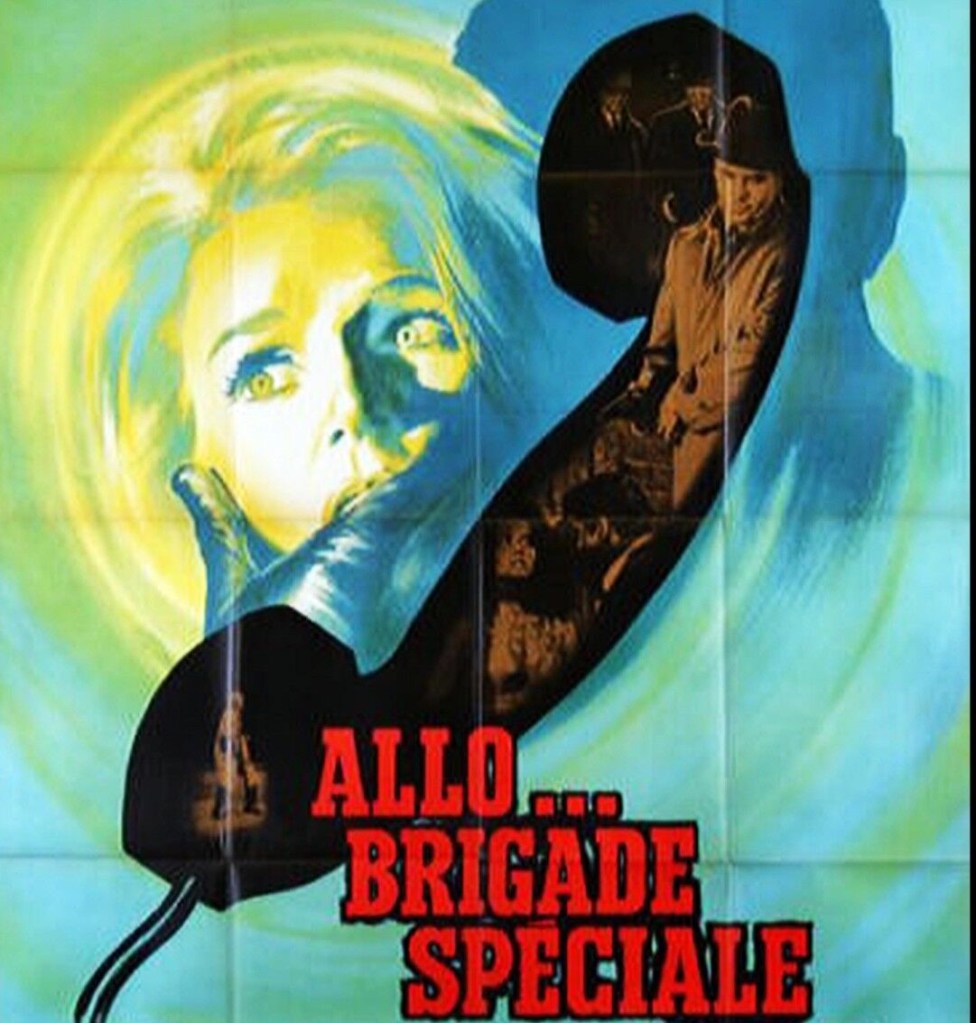

Lee Remick (No Way To Treat A Lady, 1968) continued to build on her exceptional promise. Jo Van Fleet (Cool Hand Luke, 1967) gets her teeth into the kind of role most actors dream of. You can spot Bruce Dern (Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, 2019) in his first role.

An unusual approach to the screenplay, too, by Paul Osborn (The World of Suzie Wong, 1960). Like The Towering Inferno (1974) a decade later, this derived from two novels – Dunbar’s Cove by Borden Deal and Mud on the Stars by William Bradford Huie (The Americanization of Emily, 1964).

Despite my ecological reservations, still stands up..