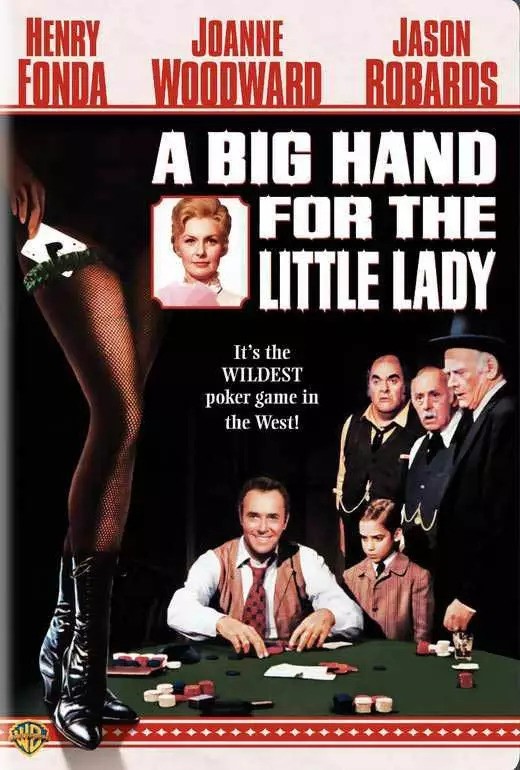

An absolute delight. Thrilling too. Knocked sideways in the box office battle of the poker pictures by the purportedly classier The Cincinnati Kid (1965) with Steve McQueen in one of his most iconic roles facing off against Edward G. Robinson and underrated ever since. But this more than holds its own against the Norman Jewison number. In part because of terrific untypical performances from Once Upon a Time in the West alumni Henry Fonda and Jason Robards.

I get my daily movie fix late at night when the rest of the house is abed and disinclined to share my interest in old movies but when at a critical point my DVD gave out instead of, as would be more sensible, giving up and going to bed, I spent ten minutes frantically scouring YouTube for a copy, even glancing hopefully at one in a foreign language, and expended the same time again tearing apart my DVD collection, which at one point had been sensibly arranged alphabetically until too many additions made nonsense of that arrangement, until I found another copy. Finally, I settled down, even later at night, to watch an enthralling finale.

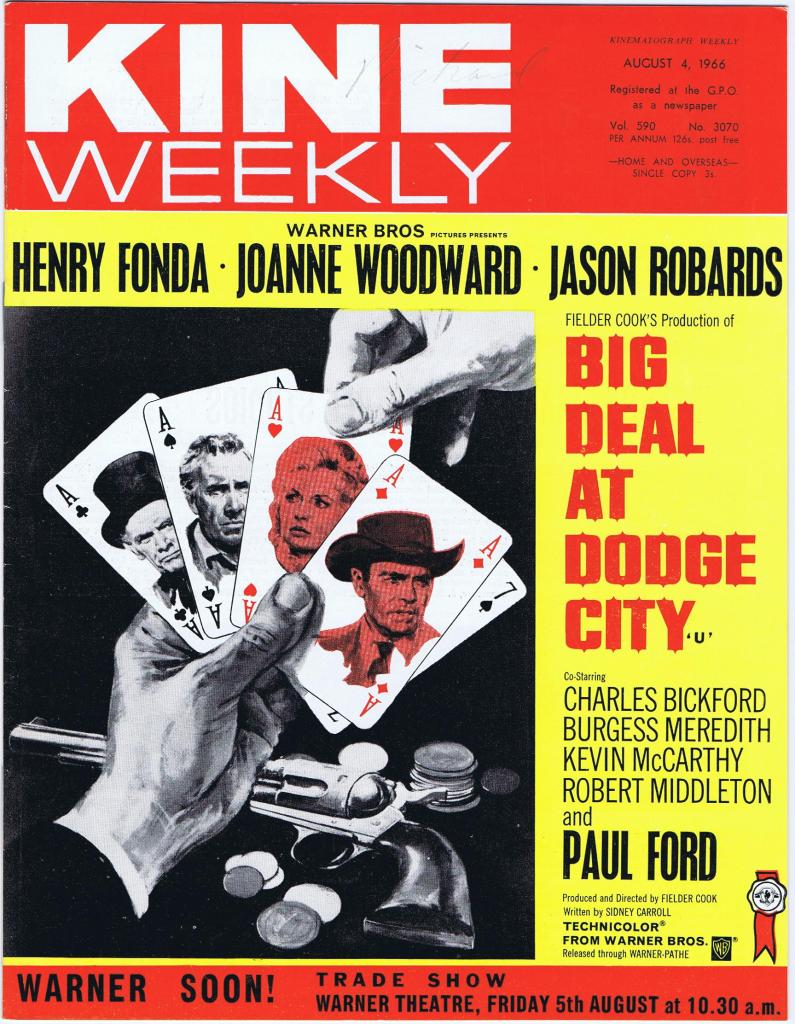

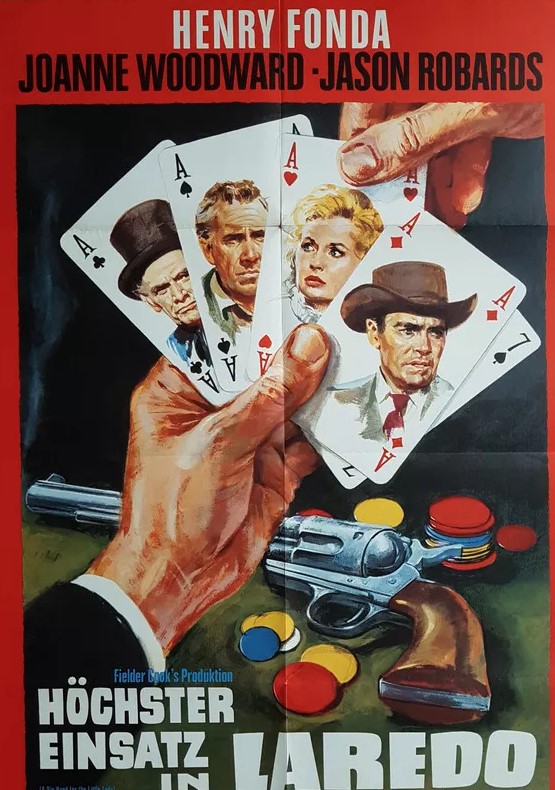

Fielder Cook (Prudence and the Pill, 1968), with only a handful of movies to his name and generally considered no great shakes as a director, plays this hand brilliantly. It reeks of mystery, as a poker table should. We begin with an undertaker’s coach racing from town to town and house to house collecting with urgency a disparate collection of people delivered to the backroom of a hotel in Laredo, Texas, where, nonetheless, the townspeople are excited beyond belief. It’s the long-awaited poker game between the five richest men in the territory.

As he stuffs more cash in the safe and pulls out bigger and bigger batches of poker chips, the hotel owner (James Berwick) is constantly badgered by his exuberant customers as to who is winning. He remains mute on that score until Doc Scully (Burgess Meredith), heading out to deliver a baby and a foal, asks the same question. Such is the medic’s local standing, the owner gives a reply. This means something to the onlookers but not to us because we have very little concept of the players.

And that remains largely the case beyond some good-humored and occasionally tense banter when we learn that Drummond (Jason Robards) abandoned his daughter’s wedding to get here and that lawyer Habershaw did likewise in court leaving his client to defend himself. And the game itself is boisterous, devoid of the cathedral-like atmosphere of The Cincinnati Kid.

But when a relatively impoverished newcomer Meredith (Henry Fonda) enters the fray the situation turns ugly as he is besieged by insult and verbal abuse as his paltry stake gets smaller and smaller. When he takes his last $3,000 – the whole sum intended to provide a new future for his wife and son on a farm near San Antonio (“San Antone” he quickly learns is the correct pronunciation) – he discovers that he is undone as his fellow gamblers raise the bidding beyond his amount.

At which point he collapses, potential heart attack. Doc Scully hauls him off on a makeshift stretcher. The money will be defaulted unless upstanding wife Mary (Joanne Woodward) of the anti-gambling fraternity can be called upon to play out his hand in a game of which she is completely ignorant and, more to the point, raise the cash to be allowed to continue.

The players sneer at what she has to offer. The richest men in the territory have no need, even at a cut-price offer, of a gold watch and a new team of horses and wagon. For a moment you think Mary, seeing her family fortunes going downriver, is going to offer herself as collateral, but instead, she decides to try and get a loan, based on the hand she holds, from the bank. You might as well try to get blood out of a stone from bank owner Ballinger (Paul Ford). Maybe she has something worth more to him as collateral than watch and wagon.

I won’t spoil it for you by revealing the ending but it’s well worth the wait and the mystery.

I was knocked out by Henry Fonda’s acting. Usually, he is gritty, upstanding, sometimes the last man standing, and his smile is often more of a grimace. Here, he is nervous, jumpy, anxious, and desperate, the reformed gambler unable to resist temptation, persuading himself that this one last game would be worth all the broken promises given his wife. His smile is so ingratiating you wouldn’t want anything to do with it. As regards the temptation facing addicts it’s on a par with the heroin victim of The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) and the alcoholics of Days of Wine and Roses (1962).

With him removed from the equation, the acting lot falls to Joanne Woodward (A Fine Madness, 1966). She’s the prim opposite and doesn’t overplay her hand, restraining as best possible her confusion and fear. And this is a very fine turn from Jason Robards, most commonly accused of over-acting or under-acting, and here he gets the balance just right, volubility matched by arrogance, and a determination not just to win but to demolish an opponent.

A raw truth is expored here. Winners don’t just like winning – the medal, the lap of honor, the pile of cash, all that jazz – but they enjoy more seeing the defeat of their opponent, savoring that disgrace. This ain’t the kind of game that ends in a handshake or embraces sportsmanship. This is real in a way that The Cincinnati Kid is not.

There are a couple of familiar faces, John Qualen (The Sons of Katie Elder, 1965), and Charles Bickford (Days of Wine and Roses) in his final movie. The rest of the cast is largely anonymous, there to add febrile excitement, with hollering and racing around, desperate to keep up with the action.

Screenwriter Sidney Carroll had been here before, the big stakes, no-hoper taking on the world in The Hustler (1961) but he and Cook had managed a small-screen rehearsal of this picture a few years before on U.S. television in the DuPont Show of the Week series.

Every now and then, as I’ve maybe mentioned before, one of the joys of this little odyssey into the world of the 1960s movie is that you come across a little gem.

This one sparkles.