Surprisingly good World War One spy yarn full to bursting with clever ruses and pieces of deception and ending with a stunning depiction of carnage on the Western Front. Loosely based on the life of Elsbeth Schragmuller, it fell foul on release to British and American hostility to the Germans actually winning anything.

The film breaks down into three sections: the unnamed Doktor (Suzy Kendall) landing at British naval base in Scapa Flow in Orkney to plan the death of Lord Kitchener; a flashback to France where she steals a new kind of poison gas; and finally on the Western Front where, disguised as a Red Cross nurse, she masterminds an attempt to steal vital war plans. She is hampered by her emotions, romance never helpful for an espionage agent, and her addiction to morphine.

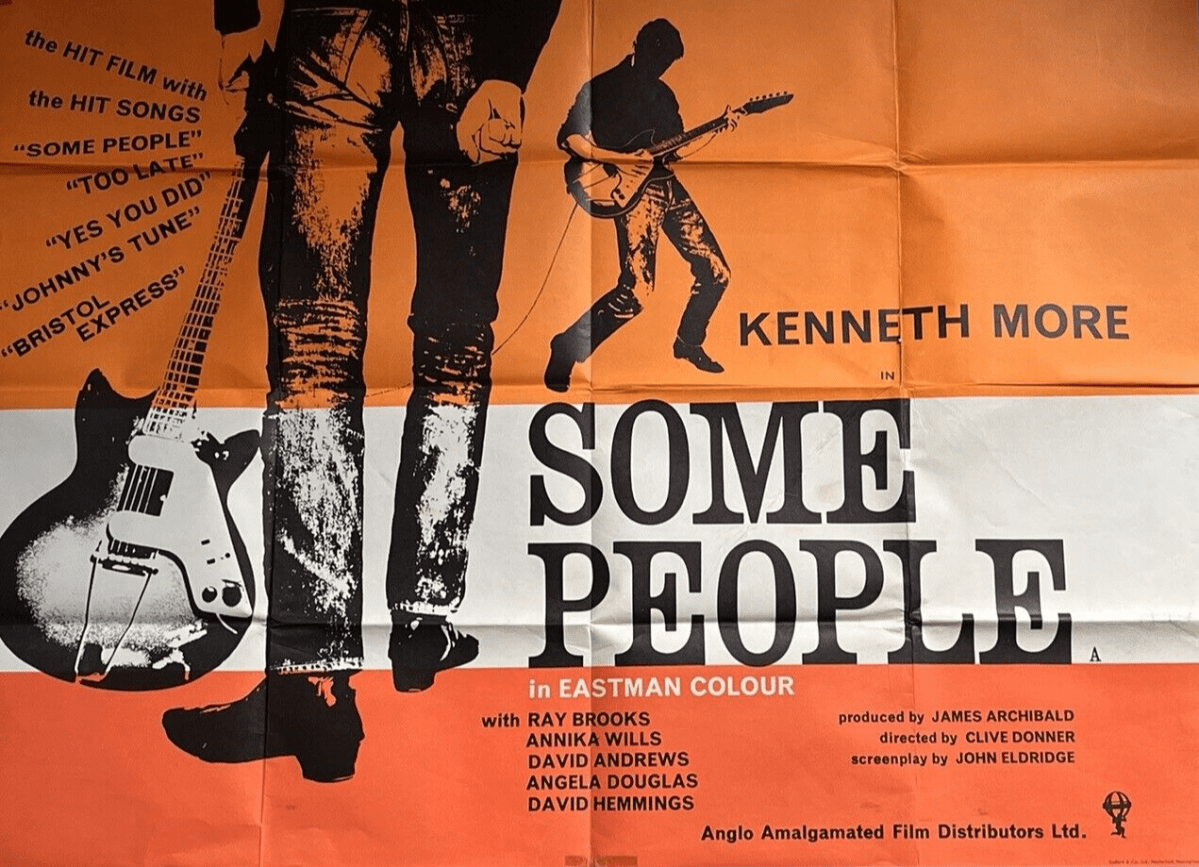

Duelling spymasters the British Colonel Foreman (Kenneth More) and the German Colonel Mathesius (Nigel Green) both display callousness in exploiting human life. The films is so full of twists and turns and, as I mention, brilliant pieces of duplicity that I hesitate to tell you any more for fear of introducing plot spoilers, suffice to say that both men excel at the outwitting game.

I will limit myself to a couple of examples just to get you in the mood. Foreman has apprehended two German spies who have landed by submarine on Scapa Flow. They know another one has escaped. The imprisoned Meyer (James Booth) watches his colleague shot by a firing squad. Foreman, convinced Meyer’s courage will fail at the last minute, instructs the riflemen to load up blanks. Before a shot is fired, Meyer gives up and spills the beans on the Doktor only to discover that Foreman faked the death of his colleague.

And there is a terrific scene where the Fraulein, choosing the four men who will accompany her on her final mission, asks those willing to die to step forward. She chooses the ones not willing to die. When asking one of these soldiers why he stayed back he replied that she wouldn’t want to know if he could speak Flemish if he was so expendable.

But the Fraulein is always one step ahead of her pursuers, changing clothes and hair color to make redundant any description of her, and knowing a double bluff when she sees one. In France, disguised as a maid, she turns seductress to win the trust of scientist Dr Saforet (Capucine) and in the final section takes command of the entire operation. It’s unclear whether this is her motivation to turn spy or whether at this point she is already an accomplished agent.

What distinguishes this from the run-of-the-mill spy adventure is, for a start, not just the female spy, how easily she dupes her male counterparts, and that the British are apt just to be as expedient than the Germans, but the savage reality of the war played out against a British and German upper class sensibility. When a train full of Red Cross nurses arrives at the front, the wounded men have to be beaten back; Foreman thinks it unsporting to use a firing squad; a German general refuses to award the Fraulein a medal because Kitchener was a friend of his; and the Doktor’s masquerade as a Red Cross nurse goes unchallenged because she adopts the persona of a countess.

Far from being an evil genius, the Doktor is depicted as a woman alarmed at the prospect of thousands of her countrymen being killed and Germany losing the war. In order to cram in all the episodes, her later romance is somewhat condensed but the emotional response it triggers is given full vent. And there is tenderness in her affair with Dr Saforet, hair combing a prelude to exploring feelings for each other.

Apart from The Blue Max (1966), depictions of the First World War were rare in the 1960s, and the full-scale battle at the film’s climax is exceptionally well done with long tracking shots of poison gas, against which masks prove little deterrent, as it infiltrates the British lines. The horror of war becomes true horror as faces blister and, in one chilling shot, skin separates from bone and sticks to the barrel of a rifle.

If I have any quibbles, it’s a sense that there was a brilliant film to be made here had only the budget been bigger and veteran director Alberto Lattuada (Matchless, 1967) had made more of the suspense. Suzy Kendall (The Penthouse, 1967) easily carries the film, adapting a variety of disguises, accents and characters, yet still showing enough of her own true feelings. Kenneth More (Dark of the Sun, 1968) in more ruthless mode than previous screen incarnations, is excellent as is counterpart Nigel Green (Deadlier than the Male, 1967) but James Booth (Zulu, 1963) has little to do than look shifty. Capucine (The 7th Dawn, 1964) has an interesting cameo.

Ennio Morricone (Once upon a Time in the West, 1969) has created a masterly score, a superb romantic theme at odds with the discordant sounds he creates for the battles scenes.

Collectors of trivia might like to know that Dita Parlo had starred in a more romantic British version of the story Under Secret Orders (1937) with a German version, using the same actress, filmed at the same time by G.W. Pabst as Street of Shadows (1937).

This is far from your normal spy drama. Each of the main sequences turned out differently to what I expected and with the German point-of-view taking precedence makes for an unusual war picture. I enjoyed it far more than I expected.