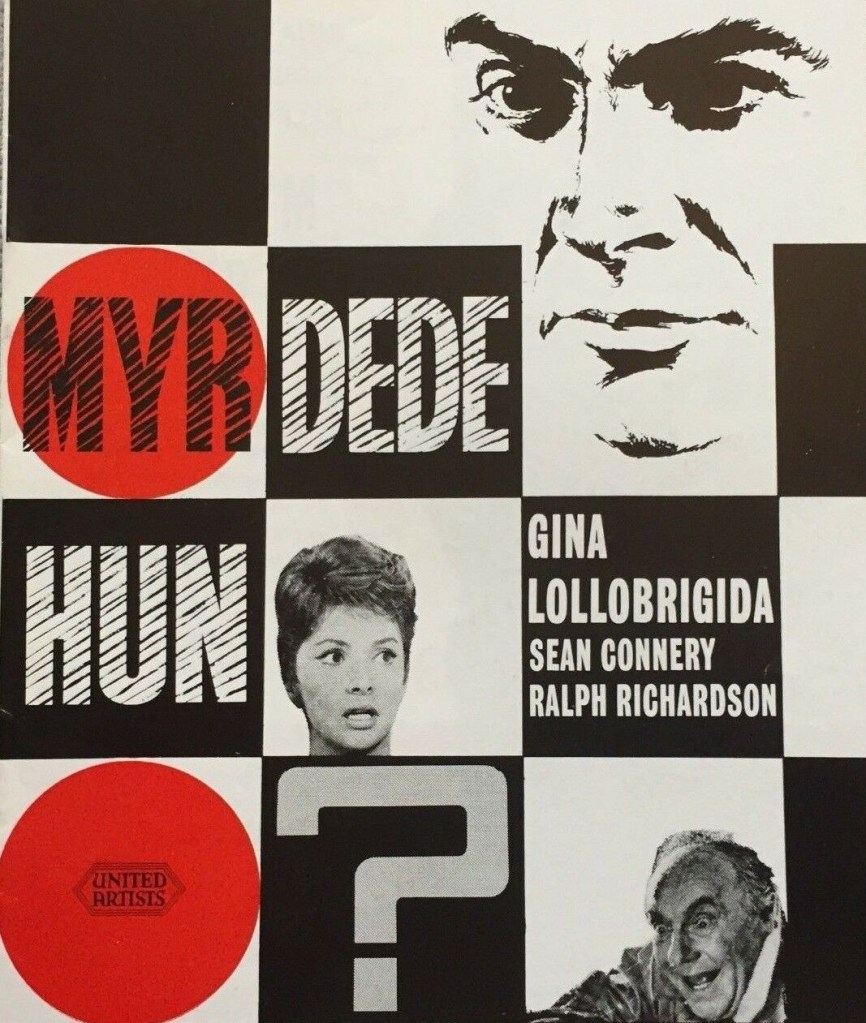

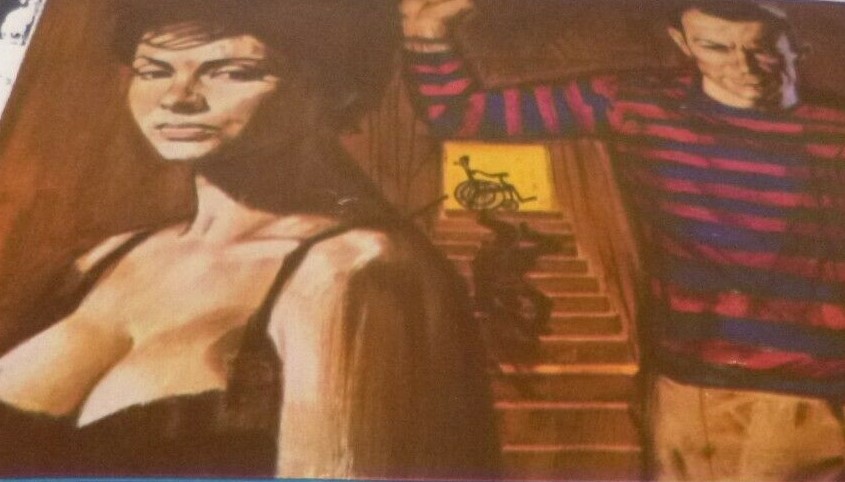

In a plot worthy of Hitchcock without that director’s sly malice, rich playboy Tony (Sean Connery) conspires with not-so-innocent nurse Maria (Gina Lollobrigida) to rid himself of heinous upper-class racist misogynistic bully Charles (Ralph Richardson), his uncle. Beyond a savage case of entitlement, Tony has good reason to hate the wheelchair-bound multi-millionaire, blaming him for his father’s suicide and for seducing his widowed mother, now dead. Tony’s ploy, in part by opposing the very idea, is to get Maria to marry Charles, inherit his fortune and provide himself a £1 million finder’s fee when the seriously ill old man dies.

Maria’s refusal to kowtow to the old man and her initial resistance to Tony make her all the more desirable to both. When Maria saves the old man from a potential heart attack, he is moved enough to marry her and draw up exactly the will the pair want. But when he suddenly dies, Maria surprises herself by the depth of emotion she feels.

But that soon changes when she comes under suspicion. A bundle of complications swiftly change the expected outcome. A police inspector (Alexander Knox) doubts cause and place of death.

The first half is the set-up, the various figures being moved into place, not quite as easily as might have been anticipated, which adds another element of tension. Charles is such a hideous person nobody could lament his passing, but still his vulnerability, not just his wheelchair confinement but his love of music, his better qualities coming to the fore as the result of Maria’s presence, accord him greater sympathy than you would imagine.

That the otherwise gallant Tony’s entitled life depends entirely on his uncle’s good wishes lends him an appealing frailty. The nurse’s principles safeguard her against being taken in by riches alone, but there is a sense that she has used her physical attraction in the past to her advantage.

After the first two James Bond pictures, this was Sean Connery’s first attempt to move away from the secret agent stereotype and in large part he is successful. As amoral as Bond, he could as easily be a Bond villain, smooth and charming and larger than life and superbly gifted in the art of manipulation, the kind of putting all the pieces in place that Bond villains excelled in.

It will come as a surprise to contemporary viewers that he is merely the leading man, not the star. Gina Lollobrigida (Go Naked in the World, 1961) receives top-billing because she carries the emotional weight, initially perhaps as cold as Tony, but her attitude to Charles changing after marriage, meeting a need that Tony would not consider his to fulfill, and beginning to regret going along with any devious plan. That she then discovers she may merely be a pawn rather than a partner creates the dilemma on which the final section of the film depends for tension.

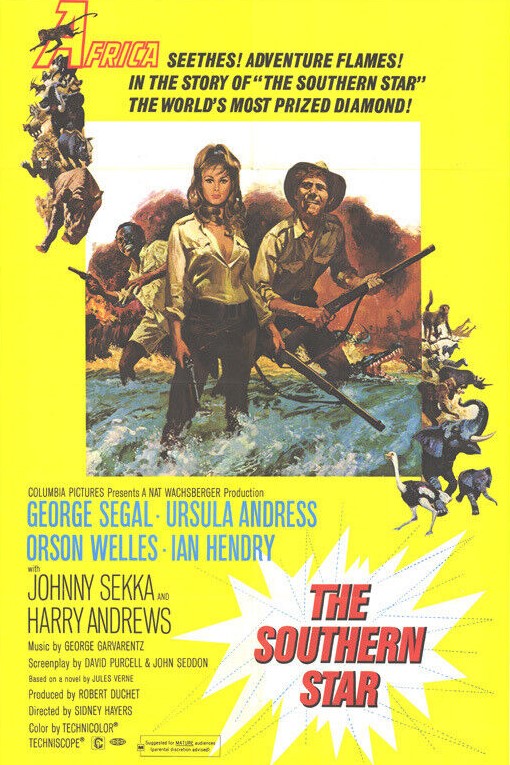

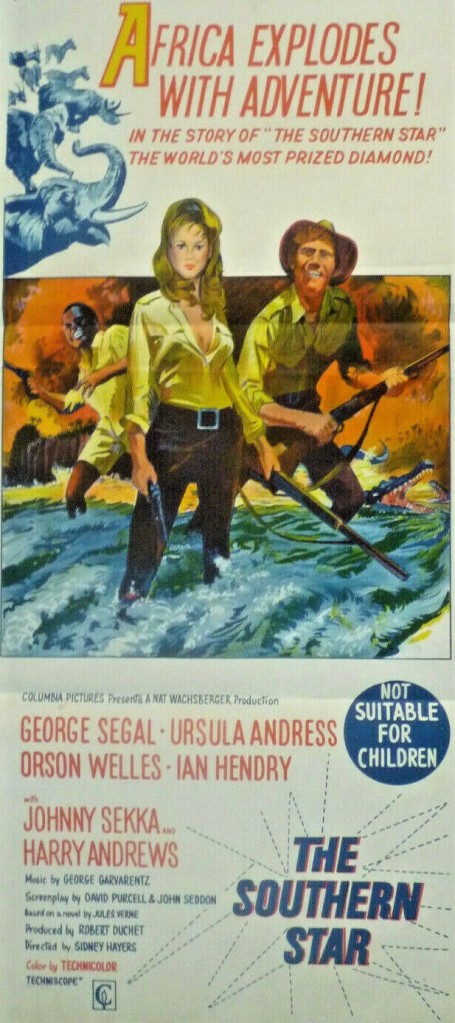

Both actors are excellent, exuding star wattage, the screen charisma between them evident, and audiences craving the pairing of Connery with an European female superstar will be well satisfied. Lollobrigida has the better role, requiring greater depth, but it is romance as duel most of the way. Ralph Richardson (Khartoum,1966) has never been better as one of the worst human beings ever to grace a screen. Johnny Sekka (The Southern Star, 1969) brings dignity to the maligned servant and Alexander Knox (Khartoum) is a crusty cop.

A slick offering from Basil Dearden (The Mind Benders, 1963), with one proviso – see seaparate article for the racism in this film. Written by Robert Muller (The Beauty Jungle, 1964) and Stanley Mann (The Collector, 1965) based on the novel by Catherine Arley.

Could have done with expending less time on the set-up and getting to the meat of the thriller quicker.