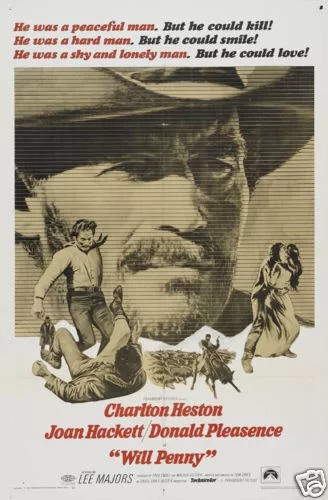

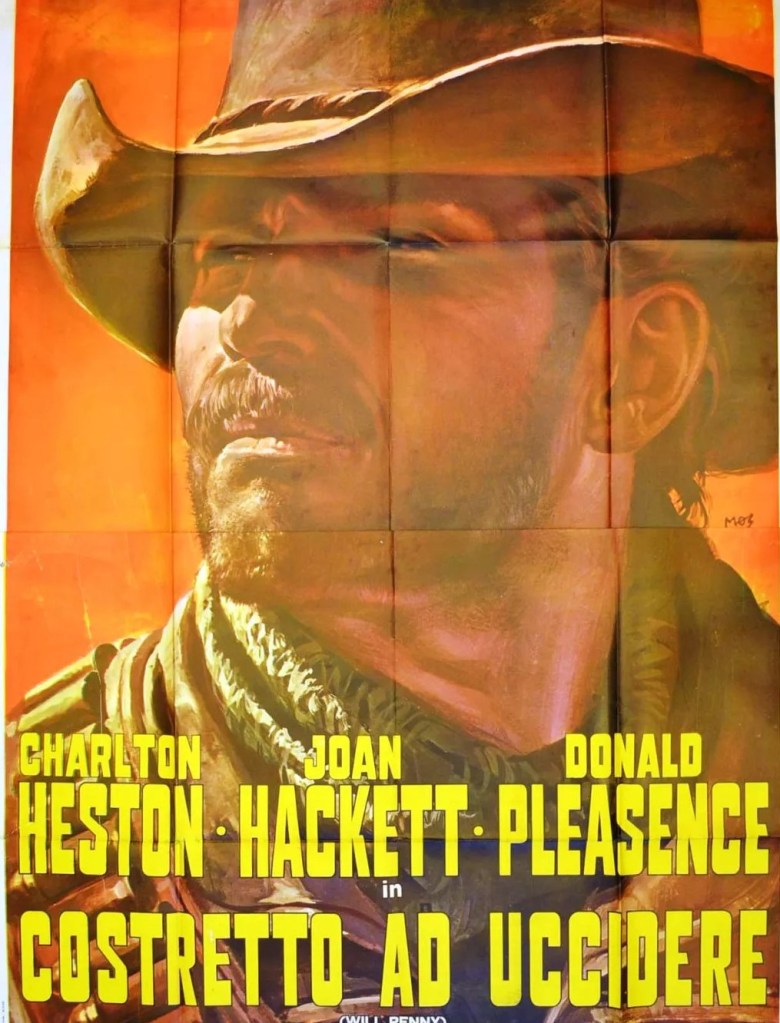

Tale of two westerns. On the one hand two undoubtedly fine performances contribute to an excellent realistic somewhat downbeat cowboy yarn. On the other hand a bunch of loonies jumping in every now and then as plot devices upset the wonderful tone. There had to be some other way, surely, to ensure itinerant illiterate 50-year-old cowhand Will Penny (Charlton Heston) and educated single mother Catherine (Joan Hackett) spend the winter together, other than him being bushwhacked by mad-eyed Preacher Quint (Donald Pleasance) and left to die.

This kind of sub-plot, you know where it’s going to end, even though, in this case, it goes down a few bizarre routes. Luckily, the main narrative continues to surprise in interesting fashion.

Like its modern equivalent The Misfits (1961), this mostly revolves around simple-minded cowboys who enjoy simple pleasures, drinking and fornicating, at the end of a hard trail ride. Will looks no further ahead than his next job. He’s easily the oldest of the cowboys and we’re introduced to him getting a telling off for trying to steal a few biscuits from the trail cook. He’s constantly razzed by the younger guys, though he’s able to take care of himself. At trail’s end, he hooks up with Blue (Lee Majors) and Dutchy (Anthony Zerbe) who, unexpectedly, find themselves in a shooting match with Quint’s family.

Dutchy comes off worst, a bad gunshot wound accidentally self-inflicted. The next few sequences are terrific. Dutchy, thinking he’s going to die, wants to go out drinking gutrot whisky and telling tall tales of heroism to Catherine who they encounter at a tiny trading post. There’s generally a callous disregard for the wounded. Even so, Blue and Will take the wounded, now drunk, man to the nearest town where the Dr Fraker (William Schallert) doubles as the local barber.

Will finds a job tending an outlying herd but finds the cabin that goes with it inhabited by Catherine and son Horace (Jon Gries). Out on the job, he’s attacked, robbed and left for dead by Quint and sons Rafe (Bruce Dern) and Rufus (Gene Rutherford). He manages to find his way back to the cabin and is tended by Catherine. Horseless and not fit for work, he decides to hole up in the cabin, fixing it up to withstand winter.

They’re wary of each other, but he bonds with the boy, and gradually they warm to each other, despite the two-decade age gap. She’s been let down so often by men, husband, trail escort etc, that she clearly finds something admirable in his dependability.

And we would probably be headed for a heartbreak ending. We’ve already seen how easy it is to be injured in the cowboy game, and how unemployable that renders a man, so the prospects of an ageing cowhand, who knows no other existence, settling down with an idealistic younger woman seem remote.

In any case, there’s a ways to go before that time comes since at Xmas the Quints reappear, beat Will up again and tie him up. You’d expect them to have their way with Catherine but there’s a twist in that Preacher has sized her up as a wife for one of her sons. While they are fighting over her, Will escapes.

Luckily, his old buddies come looking for him and he’s got a sack of sulphur (purpose never explained) so he smokes out the bad guys and they all get shot, leaving Will and Catherine with their heart-breaking moment.

As I said, two quite dfferent movies at odds with each other. Charlton Heston (Number One, 1969) is transformed. His trademark screen persona disappears under this quite different, diffident, awkward, character and there’s an argument to say this is his best-ever performance. The scenes where he tries to cover up his illiteracy, shies away from learning a Xmas tune, and explains his theories on the frequency of bathing are outstanding.

If you only know Joan Hackett from Support Your Local Sheriff (1969) you wouldn’t recognize her here, contained and watchful, rather than somewhat crazy in the James Garner picture.

While this pair gell, Donald Pleasance (Soldier Blue, 1970) et al stand out like a sore thumb as if they’ve decided to try and hijack the picture with some pointless over-acting. An excellent supporting cast includes Lee Majors (The Six Million Dollar Man) in his debut, Ben Johnson (The Undefeated, 1969), Slim Pickens (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967), Clifton James (Cool Hand Luke, 1967), Bruce Dern (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They, 1969) – in full chipmunk-teeth mode – and Anthony Zerbe (Cool Hand Luke).

Tom Gries (100 Rifles, 1969), as writer and director, makes an excellent impression.

The cowboy and homestead sections work incredibly well, what passes for action and plot drag it down. Still, on balance, well worth seeing.