Mirisch could easily lay claim to be the top independent production outfit of the 1960s generating hits like The Magnificent Seven (1960), West Side Story (1961), The Great Escape (1963), The Pink Panther (1964) and its sequel A Shot in the Dark (1964), The Russians Are Coming, Russians Are Coming (1966), In the Heat of the Night (1967) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) plus a shelf load of Oscars and Oscar nominations. But dependence on a partnership with Billy Wilder in the 1970s and a more lackluster performance at the box office – with the noted exception of Fiddler on the Roof (1971) – spelled the end of its 17-year relationship with United Artists, which was reeling from financial losses and under new management.

The company found a new partner in Universal which had a series of deals with other major producers like Alfred Hitchcock, Zanuck and Brown (Jaws, 1975) and George Seaton (Airport, 1970). Mirisch was not in any financial trouble, having severed ties with UA after Mr Majestyk (1974), a major success abroad, and recovered its development costs for Wheels, based on the Arthur Hailey novel but the script rejected by UA, from Universal which turned it into a mini-series.

The Universal deal was initially not as good as that enjoyed at UA. Universal charged a twenty-five per cent overhead whereas UA had charged nothing and Universal was now doing direct deals with directors rather than relying on the likes of Mirisch to tie up the talent.

Many years before, Mirisch had commissioned a script on the Battle of Midway from Donald S. Sanford who specialized in war pictures but of the distinctly low-budget variety – Submarine X-1 (1968), The Thousand Plane Raid (1969) and Mosquito Squadron (1969), none of which had enjoyed any success.

Though all of the Mirisch war pictures had concentrated on Europe, Walter Mirisch, generally the creative driving force for the production company, in his previous incarnation with Allied Artists had some experience of the Pacific War, having produced Flat Top / Eagles of the Fleet (1952), set around an aircraft carrier during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and was an avid reader of books about the Second World War.

John Ford and Louis de Rochmont had made documentaries about the Pacific naval battles. UA rejected the script twice, a shrewd move in the end because Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) lost a packet for Twentieth Century Fox. The Sanford screenplay had initially taken more of a documentary approach but after gaining the interest of Charlton Heston, who had starred in Mirisch’s The Hawaiians (1970), the script was tweaked.

Programming a war picture was a risk for the studio. There hadn’t been a big-budget war picture in five years. And while Patton (1970) and Kelly’s Heroes (1970) ended up on the right sight of the ledger book, Tora!, Tora! Tora! and Too Late the Hero (1970) were stiffs.

Mirisch signed a two-picture deal with Universal, for Midway and Wild Card with a screenplay by Elmore Leonard (Mr Majestyk). Mirisch proposed to reduce costs by using footage from naval archives, converting the original 16mm film to 35mm. The producer also took footage from Japanese film Storm over the Pacific / I Bombed Pearl Harbor (1960) – the rights cost him $96,000. Footage of the Pearl Harbor attack in Tora! Tora! Tora! doubled for shots of the attack on Midway Island. A clip of the Dolittle raid on Tokyo from Thirty Seconds over Tokyo (1944) was used in the credit sequence after “subjecting it to a sepia bath.”

After the success of Earthquake (1975), Heston was back in the top ranks of box office stars and his involvement guaranteed the green light. The U.S. Navy offered its support, not surprising since Midway was considered its greatest success.

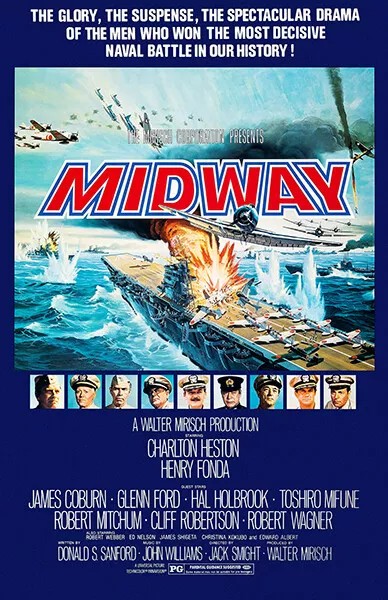

John Guillermin (The Towering Inferno, 1974) was hired to direct and Stirling Silliphant (In the Heat of the Night) signed up for a screenplay rewrite. Mirisch had determined to employ the all-star-cast device that had been an essential ingredient of many of the 1960s roadshow pictures, kicking off with Henry Fonda (The Boston Strangler, 1968), by now pretty much a spent force at the box office – he hadn’t made a picture in three years – but still a well-known name.

The amount of work involved for the other stars was minimal – mostly just one day – and, astutely, Mirisch called on stars who had worked for him in the past and who, like James Coburn (The Great Escape), Cliff Robertson (633 Squadron, 1964) and Christopher George (The Thousand Plane Raid) owed him something in terms of a career leg-up. Others included Robert Mitchum (The Sundowners, 1960), Robert Wagner (The Biggest Bundle of Them All, 1968) and Tom Selleck in an early role. Mitchum was the first of these stars to sign up, in March 1975, six weeks before the scheduled start date of April 27, followed two days later by Coburn.

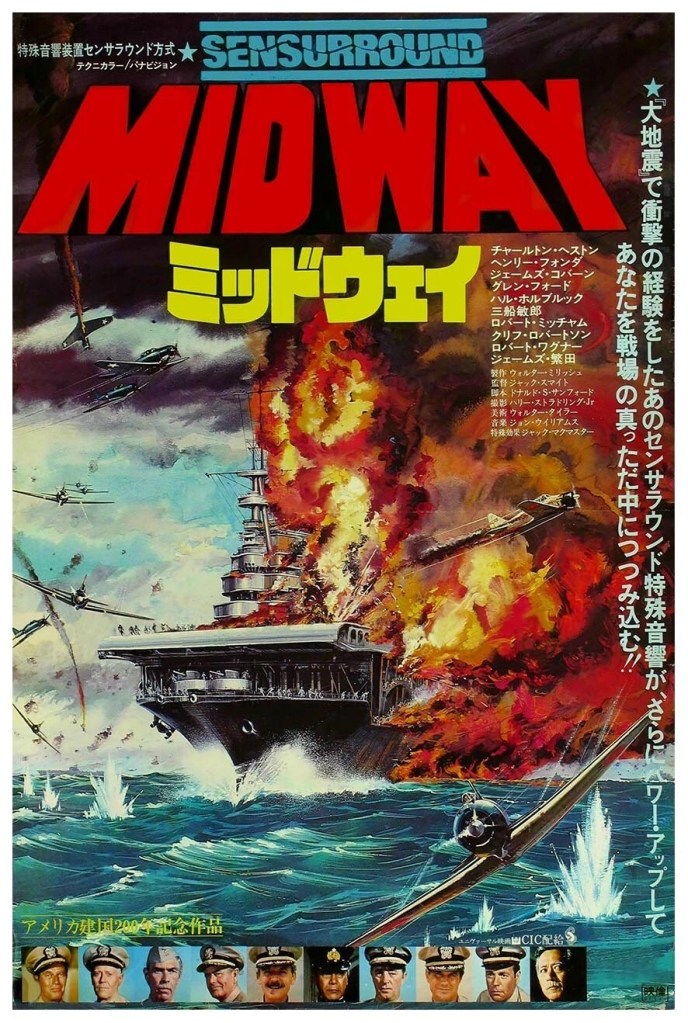

Toshiro Mifune (Red Sun, 1971) headed up the Japanese cast and proved so meticulous in his preparations that he had his uniform made by Japanese tailors. The white gloves he wore had a finger shortened on the left hand because his character Admiral Yamamoto was missing a pinky. However, despite coaching in English by actress Miko Taka (Walk, Don’t Run, 1966), his dialog was revoiced by Paul Frees.

Guillermin demanded a bigger budget to accommodate more airplanes and equipment and a longer shooting period. Two months before filming was due to start, Mirisch put his foot down and told the director he couldn’t accommodate his requests as Universal had only provided funding on the basis of Mirisch’s original idea. Guillermin walked. As far as the public was concerned, the parting of the ways was due to a “conflict of schedules.” Jack Smight, who had directed Airport ’75 (1974), a box office success and also starring Heston, was his replacement.

The Navy lent aircraft carrier U.S.S. Lexington – the last remaining World War Two carrier – while it was at sea training pilots as long as the shoot didn’t interfere with those exercises. A limited number of World War Two vintage planes – in great condition having been cared for by their owners – were permitted on board. The Navy charged the crew for accommodation – Mirisch was housed in Admiral Strean’s quarters – and meals. “We had a detailed contract with the Navy,” recalled Mirisch, “in which we agreed to stay out of their way when asked.”

On board, the crew filmed scenes, some silent and others with dialog, and “made plates for rearview projection and aerial shots of our vintage planes so positioned that we could print them into flights of six or nine.” Charlton Heston, Glenn Ford (Rage, 1966) and Hal Holbrook (The Group, 1966) were aboard and the shoot went well. A scene involving Henry Fonda was shot at Pensacola. The Florida coast stood in for the Pacific. Additional exteriors were filmed in Los Angeles at Long Beach and Point Dune with interiors at Universal.

The construction of the interiors for the Japanese aircraft carriers was so authentic Mirisch was later asked to reassemble the set for the Smithsonian Institute for a presentation there. The interpolation of the old footage was crucial and it was planned in advance where such shots would appear. The old footage was precut and scenes were shot with actors with “scene missing” in those sequences into which the old footage could be dropped. Other devices were used to ensure the background in the old footage was more lively.

The final element was in cinematic presentation. Sensurround, a precursor of Imax, had been introduced with great success by Universal to Earthquake and this added greater realism to the battle scenes. While limited to those theaters which had installed the expensive equipment, and although the roadshow was long gone, it created an “event” aspect to those viewing it in that system. In his autobiography Mirisch suggested the addition of Sensurround was last minute and sparked by the success of Earthquake. But, in fact, Universal had announced a year in advance of opening that Battle of Midway would utilize Sensurround.

Some cinema owners were outraged at the stock footage, whose proposed inclusion had been kept from them when they went into the blind-bidding process at the start of the year. Mirisch countered that there was no alternative. “A great many aircraft,” he argued, “used in the battle no longer exist.” Universal’s terms were stiff – a minimum nine-week run starting at a 70/30 split for the first three weeks in the studio’s favor, a $75,000 advance guarantee from cinemas and 5% of the gross for use of Sensurround.

With the budget kept as low as a reported $4 million it was a massive hit, picking up $20.3 million in rentals (what the studio retains of the box office gross) – sixth in the annual box office league beaten only by Oscar-winner One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, All the President’s Men with Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, demonic The Omen, Walter Matthau baseball comedy The Bad News Bears and Mel Brooks’ Silent Movie and just ahead of such offerings as Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon with Al Pacino, and comedy Murder by Death but nearly doubling the take of the more critically-acclaimed Taxi Driver, Clint Eastwood western The Outlaw Josey Wales and thriller Marathon Man also starring Hoffman. The final domestic figure amounted to $21.8 million.

Foreign figures were astonishing, especially in Japan, where its gross exceeded $4 million. The benefits of the promotional tour undertaken by Heston in the Far East were soon obvious – in Manila it beat both Jaws and Earthquake. In the annual box office league there and Hong Kong, it ranked third. In Italy it proved a “big surprise”, coming in fourth behind King Kong, Taxi Driver and a local offering.

While a successful movie could expect to benefit from television viewings – this was before the video revolution – the movie had an unusual afterlife. NBC, which had bought the rights, wanted the film to be longer, so it could be shown over two nights, thus increasing advertising and setting it up as a more prestigious event. Largely by adding plotlines to the Heston character, the running time increased by nearly an hour, which proved a bonus for the future home screening revolution.

“Of all the films that I have made,” noted Mirisch, “it produced the greatest amount of profit.”

SOURCES: Walter Mirisch, I Thought We Were Making Movies Not History (University of Wisconsin Press, 2008) pp324-339; “Readying Midway,” Variety, February 5, 1975, p6; “Universal in New Shake,” Variety, July 23, 1975, p3; “Admiral Mitchum,” Variety, March 12, 1975, p18; ”Jap Feature Footage Inserted into Midway,” Variety, June 6, 1976, p7; “Midway Big in Manila,” Variety, August 11, 1976, p24; “Big Rental Films of 1976,” Variety, January 5, 1977, p14; “Jaws Led Bangkok,” Variety, February 9, 1977, p39; “International,” Variety, June 29, 1977, p35.