You can keep your Succession dramas with families squabbling over a mere business empire. And even the more woke Snow White (2025) doesn’t remotely tackle the realities of marriage in medieval times when the role of a woman, in an era when more children died in childbirth or soon after than actually survived, was to produce an heir. And not just random in gender. But male.

So, on the one hand, you can sympathize with the dilemma of English King Henry VIII whose Spanish wife Katherine, while eminently fertile – several babies died in childbirth – had managed only one male offspring, who died shortly after birth, and one female, Mary. All the queen had given him, rails Henry (Richard Burton), are “dead sons.” So with the future of one of the biggest kingdoms in the world at stake, Henry isn’t keen to leave it in the hands of a woman. Even if he can arrange a suitable marriage, it would inevitably mean letting the kingdom fall into the hands of someone he doesn’t trust.

But in the twisted world of inheritance, here’s the rub. Henry shouldn’t be king. His elder brother Arthur should have, except he died before he could succeed to the throne. And Katherine, married to Arthur, should have been Queen. But Spain at that point was as powerful, if not more so, than England, so Henry decided to marry his sister-in-law, on the basis that the marriage was never consummated, and the Pope, the authority in such matters, gave the go-ahead, glossing over the technicality of what was considered in those days incest.

So, Henry comes up with a cunning plan. He will go trophy-hunting and marry a younger wife. This isn’t just because he’s fallen in love with Anne Boleyn (Genevieve Bujold). He doesn’t have to marry her to have sex with her. He’s already having sex with her mother (Valerie Gearon) with the tacit approval of her father (Michael Hordern) who receives benefits in kind.

To add complication, Anne is promised in marriage already, and deeply in love. Siring a bastard son would inevitably cause an inheritance battle. So legitimizing the relationship seems the only way forward. This time the Pope isn’t keen, mostly because the Spanish have invaded the Vatican and if he wants to survive he can hardly annoy his captors.

But when the Pope refuses, Henry takes the nuclear option, and splits from the Catholic Church, not just taking advantage of the old church vs state argument, but also made aware by Thomas Cromwell of the sudden increase in wealth acquiring the items of the Catholic Church would bring.

Sorry to bore you with a history lesson but this intriguing backdrop – as well as the dazzling performances – is what twists this away from lush costume confection into riveting drama. This was the peak of a trend in historical movies that shifted the emphasis from heroic action to the down’n’dirty. Camelot (1967) to some extent had begun the trend but only dealt with infidelity and was given something of a free pass because it focused on the iconic Knights of the Round Table and a legendary love affair. The Lion in Winter (1968) primarily concentrated on inheritance.

Depending where your sympathies lay this was either corruption writ large or a battle to free the ordinary man from the yoke of religion.

Primarily, it works because it revolves around the human drive, the king refusing to bow the knee to anyone, Anne Boleyn seduced not just by gifts but by this older man who is much more virile and passionate than her younger somewhat effete fiancé (and who couldn’t be dazzled by a man risking his kingdom for her love?) – and the courtiers looking after number one, always seeking a way of winning the king’s favor, and as importantly, not losing it, for that could lead to banishment or execution.

No one dares stand in Henry’s way – except Sir Thomas More (William Squire) and here he’s merely a small subplot (not center stage as in A Man for All Seasons, 1966) – not even the religious hierarchy, especially Cardinal Wolseley (Anthony Quayle), head of the Catholic Church in England, who keeps a mistress.

The tragedy is that the cunning plan unravels. While Anne is fertile enough, she gives birth to a girl, Elizabeth (the later Virgin Queen). Convinced she’s not going to present him with the male heir he so desperately desires, he hatches a conspiracy that sees her executed for adultery and treachery, leaving him free to marry again and continue his mad obsession.

So we’ve got all the back-biting and bitching we expect from court, plus regal revelry, costumes, castles, and in the middle of it all a driven king and a feisty woman, not by any means a pushover, and not either going unwillingly into his bed. This would be a match made in heaven except that’s probably the last place, the way things stand, the king would be welcome. He’s very aware of excommunication and it shows the power of the Catholic Church that its teachings are so embedded in his brain that he fears that consequence.

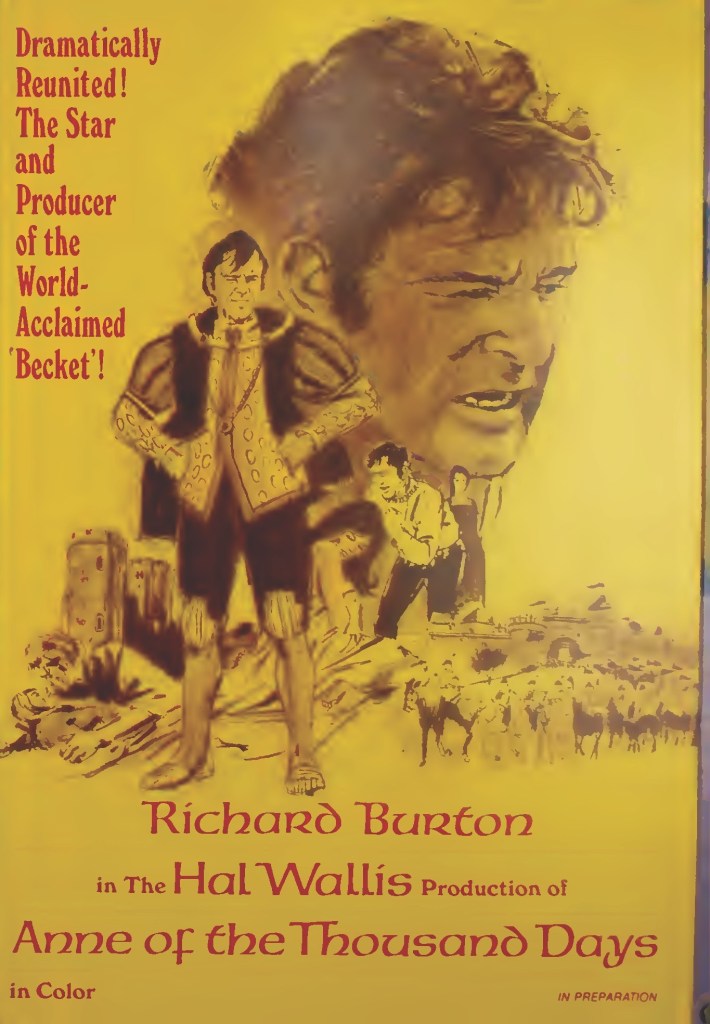

This is rich in performance – Richard Burton (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, 1965), Canadian Genevieve Bujold (The Thief of Paris, 1967) and Anthony Quayle (East of Sudan, 1964) were Oscar-nominated. The only significant figure in the production not to receive one of the movie’s ten nominations – including for Best Picture – was director Charles Jarrott who pulled the whole thing together. Maybe it was thought he was rusty, not having helmed a picture since Time to Remember seven years previously.

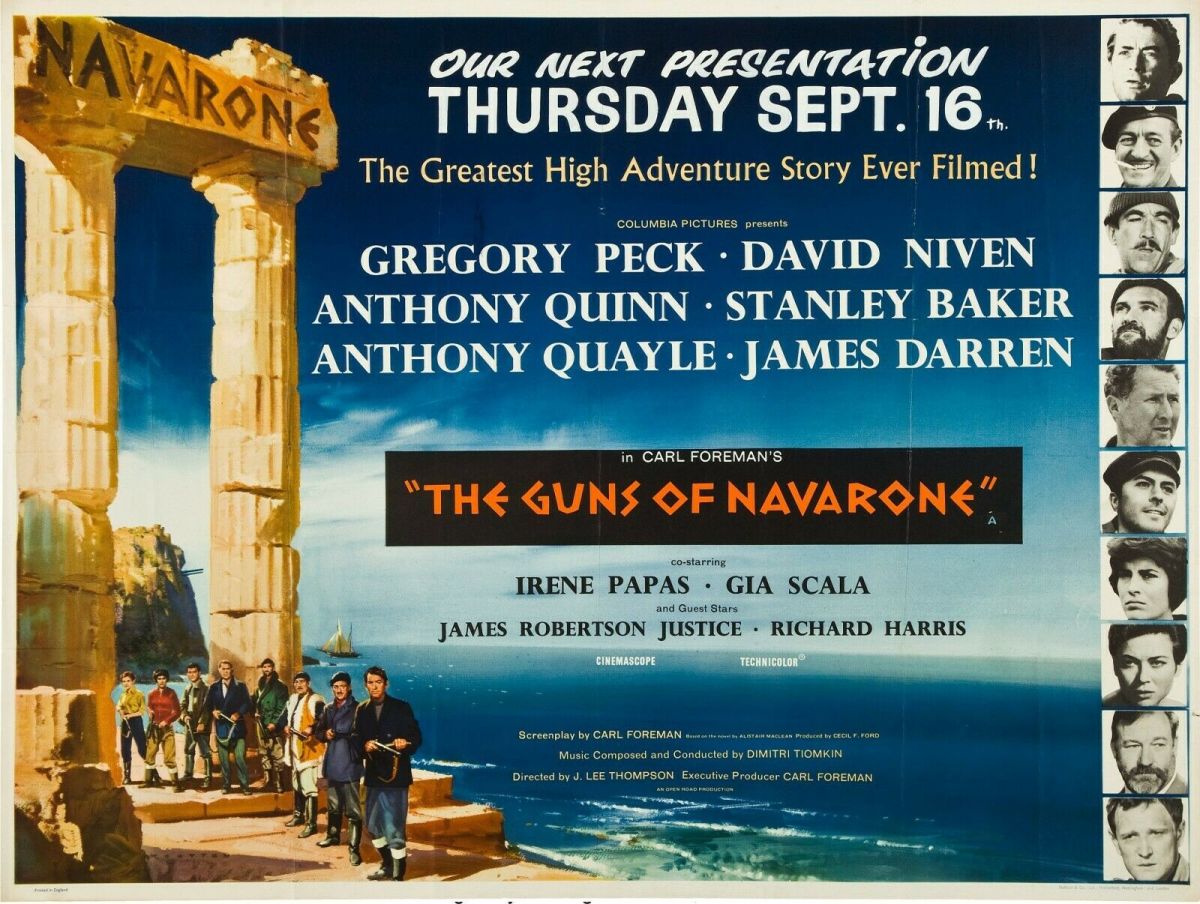

The acting is particularly well-judged by the two principals, Burton could easily have lurched into cliché, and Bujold into passivity. Others worth noting are Irene Papas (The Guns of Navarone, 1961), Michael Hordern (Khartoum, 1966), Valerie Gearon (Invasion, 1966) and Peter Jeffrey (The Fixer, 1968).

Based on the play by Maxwell Anderson (The Bad Seed, 1963), screenwriters John Hale in his movie debut and Bridget Boland (Gaslight, 1940) manage to balance what could be dry subject matter with fragility and tragedy.

There couldn’t be a better demonstration of women used as pawns and collateral damage in male power struggles.

Totally absorbing.