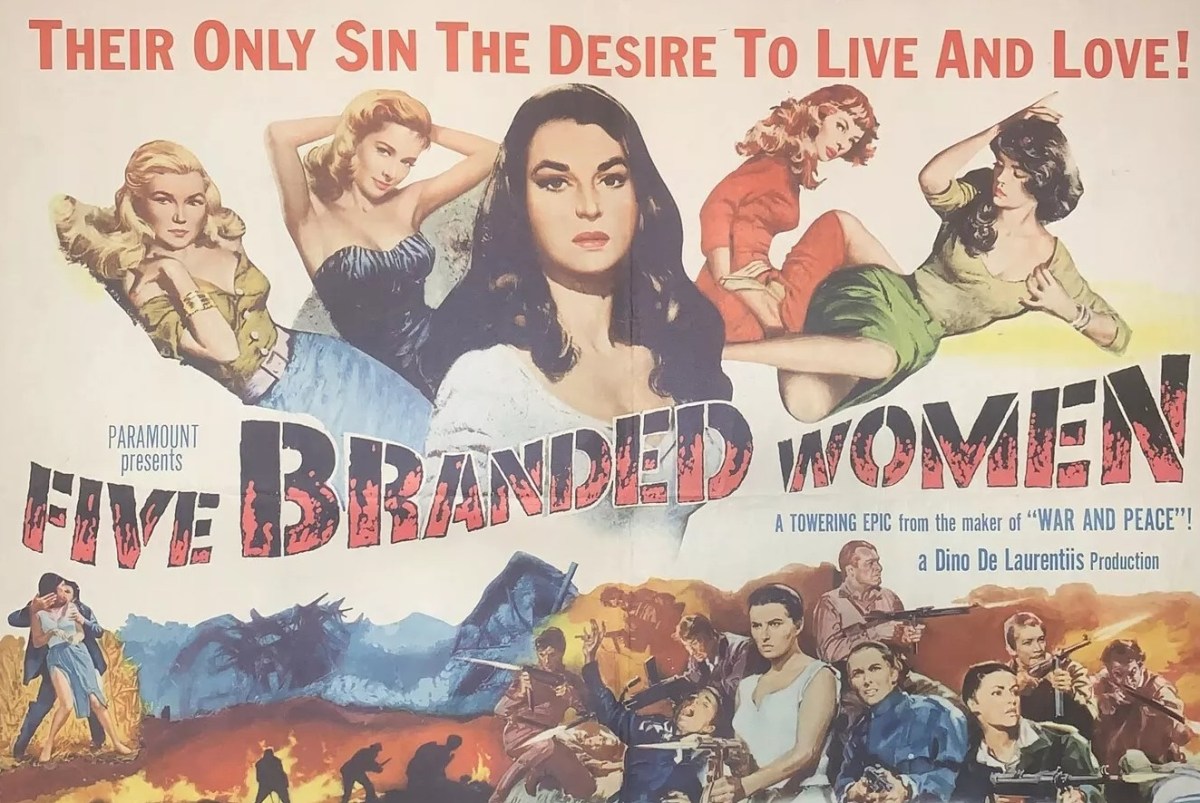

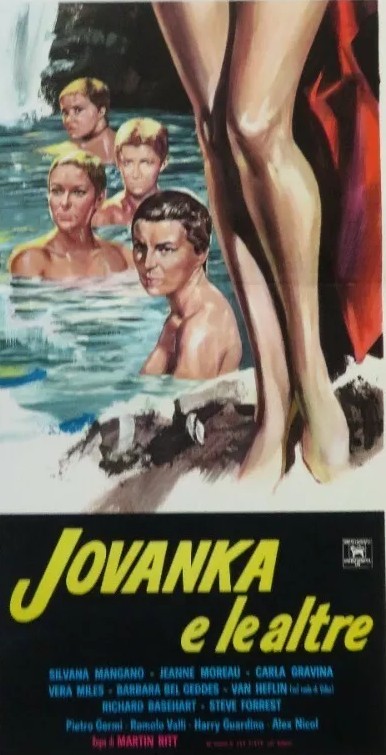

Should have qualified as that rare thing – an all-star female cast. Italian Silvana Mangano had led the arthouse revolution and kickstarted the importing of sexy Italians in international hit Bitter Rice (1949), Jeanne Moreau was a leading light in the French New Wave (and another sexy import to boot) as star of Les Liaisons Dangereuses/Dangerous Liaisons (1959), Vera Miles was hot after Psycho (1960), rising star Barbara Bel Geddes (Vertigo, 1958) another Hitchcock protegee. Never mind that the story was a serious one, the redemption of female collaborators in Yugoslavia in World War Two, there was still time for what had become very much a western genre cliché, the inability of any woman not to strip off at the sight of a waterfall – here all five go skinny dipping.

The narrative should have been clearcut as redemption tales generally are: miscreant finds salvation. But this one is pretty muddled up and the moral confusion gets in the way. While some of the women such as Ljubo (Jeanne Moreau) have sex with the occupying Germans to prevent a brother being sent to a work camp, others such as Jovanka (Silvana Mangano) simply fall in love or like widow Marja (Barbara Bel Geddes) are desperate for a child. All five have been conquests of German lothario Sgt Keller (Steve Forrest) who is castrated by the partisans. The women are humiliated by the partisans who shave their heads and the Germans cast them out of the town, Daniza (Vera Miles) part of the quintet though she denies having sex with Keller.

But it’s not just the Germans who are apt to have predatory notions about women. A pair of armed collaborators consider them fair game and attempt to rape Jovanka and Ljubo. Partisan Branko (Harry Guardino) – ostensibly in the category of good guy – attempts to rape Jovanka then seduces Daniza. The lovers are later executed by the partisans for breaking the rule not to have sex with each other. And this is where it gets mixed up. The pair were meant to be on guard when they started having sex. In consequence, three Germans sneaked into their camp and nearly caused disaster. Despite that, Jovanka, who believes she was unfairly treated in the first place in being denied love just because there was a war on, still insists that they shouldn’t be condemned for ordinary human desire.

The movie works best when it sticks to straightforward redemption or is character-driven. Given the chance Jovanka turns into an effective partisan, cutting down Germans with a machine gun, preventing rape of herself and Ljubo by shooting the attackers with a captured pistol. But she rejects an attempt at reconciliation by partisan leader Velko (Van Heflin), the one who had cut off her hair, blaming him for her unnecessary humiliation. He later tries to make amends, by trying to keep her out of brutal action.

Despite taking up arms, the women remain vulnerable to smooth-talking men. Ljubo takes prisoner Capt Reinhardt (Richard Basehart), who might fall into the “good German” category since he isn’t like Keller, was a professor of philosophy and generates sympathy because his wife died in an air raid. Taking his word of honor, Ljubo unties him. She thinks he will be exchanged for a partisan prisoner. But he knows the truth – there are no partisan prisoners available for exchange because the Germans kill them. So he tries to escape, and she machine guns him in the back.

By this point Ljubo is far from a soft touch, not likely to prattle on about women being free to love the enemy or their compatriots, and is the one who shoots Daniza as part of a firing squad when it is left to her or Jovanka to do so.

What saves it is the brutal realism of war, this predates the vengeful citizens who at war’s end would take revenge on local women who slept with any occupying Germans (Malena, 2000, showed this repercussion in Italy and it was the same throughout France). There’s certainly an innocence about female desire and Jovanka defending her right to have sex, though, surely, there would have been shame involved in having sex with even a Yugoslavian before marriage in what would still have been a devout country. So a complex defiant woman, refusing to bow down to male-enforced rules. But there’s a male corelative. Branko equally refuses to obey any rules, and his actions cause harm.

In terms of acting, Silvana Mangano and Jeanne Moreau are streets ahead of their American counterparts, and complement each other, Mangano loud and outspoken, Moreau quiet and brooding. Harry Guardino (Madigan, 1968), Richard Basehart (The Satan Bug, 1965) and Van Heflin (Once a Thief, 1965) are the pick of the males.

Martin Ritt (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, 1965), who liked to back a cause, has chosen an odd one here, and after a slow start it picks up. Written by Ivo Perilli (Pontius Pilate, 1962) from the book by Ugo Pirro.

Easily leads the pack of the women-in-wartime subgenre and despite, or bcause of, the moral confusion still well worth a look.