You wouldn’t go looking to British studio Hammer for a subtle treatise on the perils of ageing. Nor might you expect a predator to be so cruelly, and consistently, punished. Nor, for that matter, for a mirror to provide revelation given that in the traditional vampire movie one of the signs you have a bloodsucker in your midst is that a mirror does not show their reflection.

The title is something of a misnomer: while there’s bloodletting aplenty there’s zero actual bloodsucking. Hammer had taken a sideways shift into female empowerment and more obvious sexuality and gender twist with the introduction of the female vampire – beginning with The Vampire Lovers (1970), sequel Lust for a Vampire (1971) and, completing the trilogy, Twins of Evil (1972). For that matter it also pre-empted, in perverse fashion, the body swap genre of Freaky Friday (1976 etc.).

These days this would be termed the expansion of a “horrorverse” or a “Hammerverse” as the studio developed its IP since it had not abandoned the traditional Christopher Lee version, doubling down in 1970 with Taste the Blood of Dracula and The Scars of Dracula and following up with Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972).

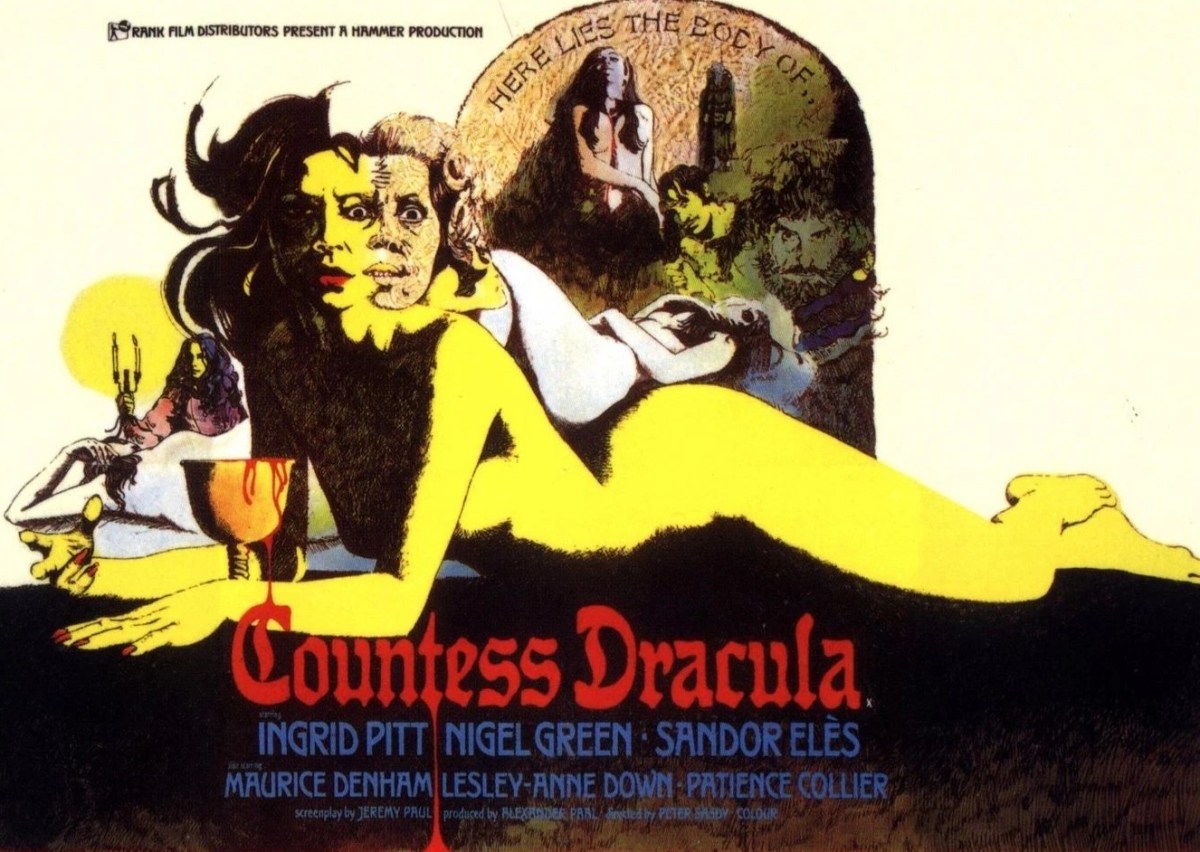

While Countess Dracula doesn’t fall into the vampiric category, neither does it so obviously exploit the sexuality and rampant nudity of the female vampire trinity. But there are other shocks in store. Be prepared for emotional punch, not something normally associated with Hammer.

The ageing beauty had been a 1960s trope as Hollywood had come to terms with finding starring roles for 1940s/1950s stars past their box office best but names – Lana Turner and Vivien Leigh among others- with still some marquee lure. And this follows a similar trajectory, older woman falling in love with younger man.

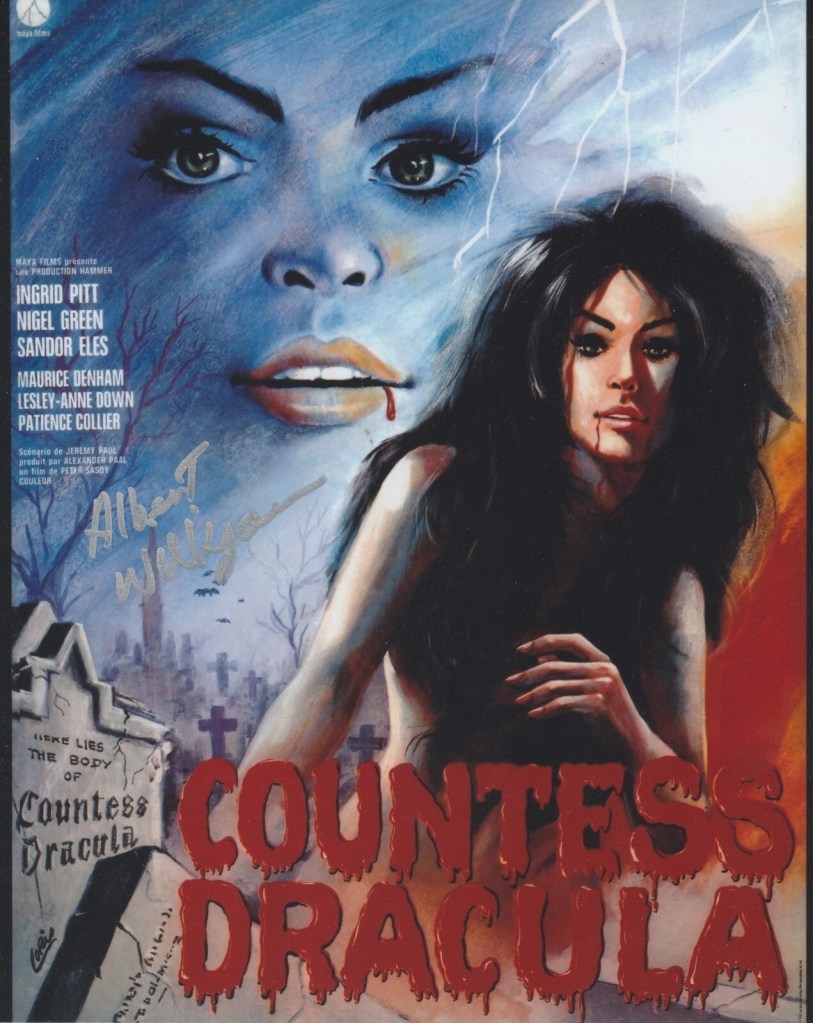

Set in Hungary in the seventeenth century, widowed Countess Elisabeth Bathory (Ingrid Pitt) discovers by accident that a touch of virgin blood rejuvenates her skin and tempts her into stealing the suitor Toth (Sandor Eles) of her 19-year-old daughter Ilona (Lesley-Anne Down). But that means kidnapping Ilona and keeping her imprisoned so Bathory can impersonate her, finding a ready supply of virgins to murder and exsanguinate, enlisting in her scheme lover Capt Dobi (Nigel Green) and maid Julie (Patience Collier).

The ruse appears to work well – at first. Believing Bathory is actually her daughter, Toth is easily seduced. But there’s a downside which is quickly apparent. What spell blood casts, it doesn’t last long. And there’s a sting in the tail. Having acted as a rejuvenating agent, when the virgin blood has run its course transformation goes the other way and turns her into an old crone.

So now, Bathory and her team enter serial killer territory, the disappearances and deaths arousing suspicion among the locals and historian Fabio (Maurice Denham), and her daughter threatening at any minute to escape her captor and turn up at the castle. And Bathory cannot give up the fantasy, not least because when the blood runs out, she’ll be unrecognizable as an old crone.

You can see where this is headed, so that’s not much of a surprise. What is astonishing is how well director Peter Sasdy (Taste the Blood of Dracula) handles the emotion. You might think the special effects do all the work that’s required, but that’s not the case. It’s Bathory’s eyes not her crumpled skin that make these scenes so powerful and in between, apart from the initial transformation, Bathory shifts uneasily between exultation that she is living the fantasy and terror that it will come to a sudden end.

Ingrid Pitt (The Vampire Lovers, 1970) has the role of her career, superbly playing a woman bewitched by her fantasy and the prospect of literally turning back the years. None of the ageing actresses that I previously mentioned manage to so well to portray that specific female agony of a beauty losing her looks. Sandor Eles (The Kremlin Letter, 1970) looks the part and Nigel Green (Fraulein Doktor, 1968), while shiftier than usual, also has to scale more emotional heights than normal, in not just having to countenance his lover going off with another man but helping her to do so. Lesley-Anne Down (The First Great Train Robbery, 1978) makes a splash.

More than ably directed by Sasdy, from a screenplay by Jeremy Paul in his debut based on the book by Valentine Penrose.

I’m not sure how well this went down with vampire aficionados and suspect there was audience disappointment, but there is more than enough depth to make up.