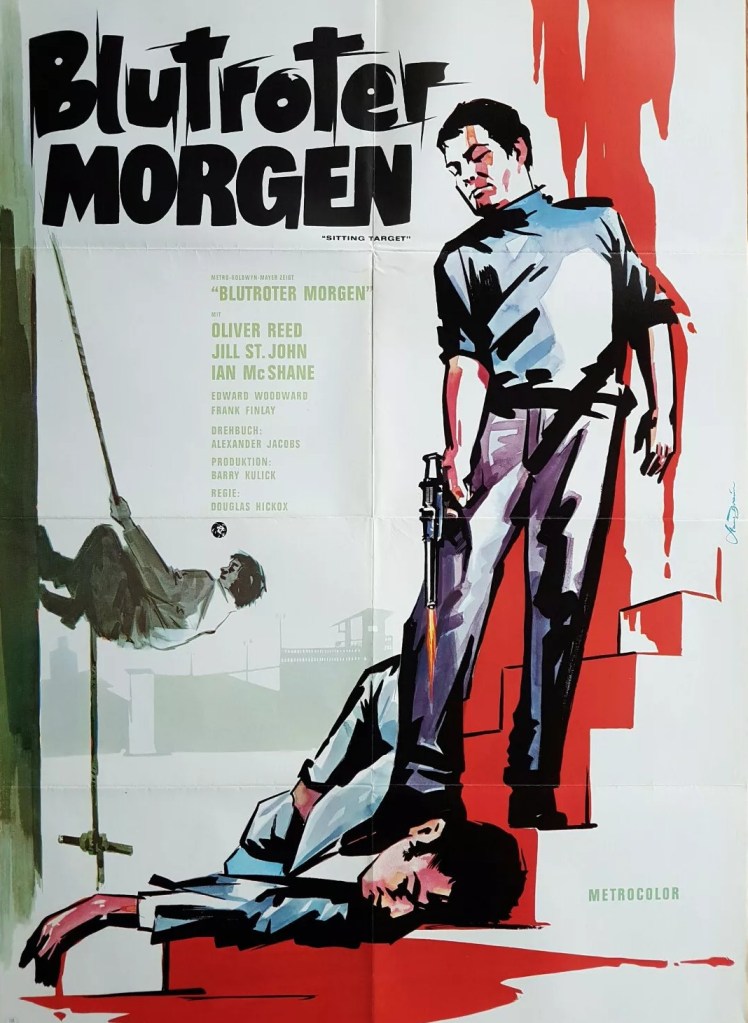

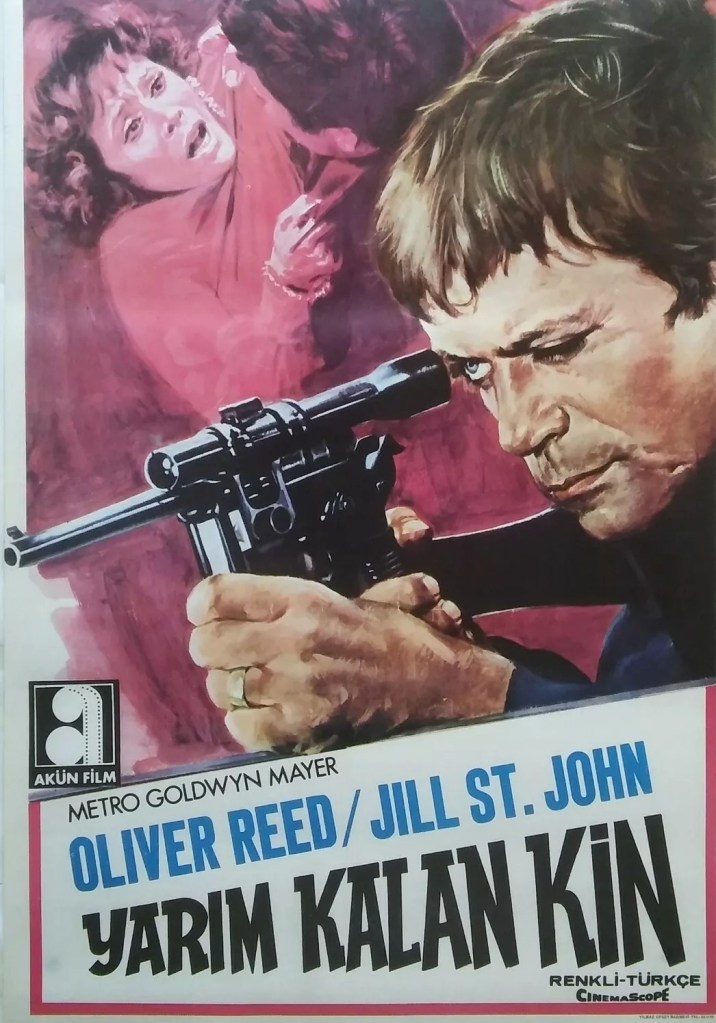

Forms a neat trilogy with British Noir New Wave gangster pictures Get Carter (1971) and Villain (1971) both with topline stars attached in the form of Michael Caine and Richard Burton. Laden with atmosphere and intrigue, this carries hefty emotional power as a very tough guy struggles to show his gentler side. The moral of the story is that brains always trump brawn. And it’s one of these movies where the truth only unravels when you hit the twist at the end and every character is shown in quite a different light.

Like Get Carter, this is a revenge picture. Discovering girlfriend Pat (Jill St John) is pregnant by another guy, imprisoned bankrobber Harry (Oliver Reed), serving a 15-year stretch for murder, is turned into a “lethal weapon” by the very thought and determines to break out and kill her. And at the same time collect the loot from his last bank robbery.

His escape, masterminded by the gentlemanly MacNeil (Freddie Jones) and accompanied by long-time buddy Birdy (Ian MacShane), is a tense, exciting sequence. First stop outside is to strongarm another gangster into supplying a Mauser that can be turned, a la Day of the Jackal, into a long-range rifle.

And while the movie brings into play the standard trope of villains seeking their share of the loot, it also hangs on another standard wheeze of the 1960s B-picture of the woman as bait. Anticipating that Harry will make a beeline for his loved one, but unaware of his nefarious intent, Inspector Milton (Edward Woodward) has her under police guard. But the likes of Harry always finds a way to sneak in, which triggers police pursuit, in the course of which Harry commits the unpardonable crime of shooting a cop – the villain world only too aware of the severe repercussions.

There’s a stop-off at the apartment of the moll (Jill Townsend) of Mr Big, Marty (Frank Finlay). That doesn’t go as planned, but still they manage to uncover a hidden sack of cash leaving Harry to knock off, sharpshooter style, the unfaithful girlfriend.

And then the pair make a getaway….Not quite. Birdy turns out to be greedy and wants all the robbery cash for himself and attempts to shoot Harry. That would be enough of a twist to be getting on with but there are a few stingers to come. Pat’s not dead – Harry (too far away to identify her face) just shot a policewoman on protection duty standing in her window. Pat’s not pregnant either, just stuffed a cushion down her jumper to complete the pretense. And she and Birdy are an item. And it’s clear that Birdy simply purloined Harry’s rage to get him to do the dirty work involved in the escape and dealing with the other gangsters.

Except in the case of being willing to knock off his longtime business partner, Birdy, you see has always been averse to violence, cowardly not to put too fine a point on it, though quite capable of pouring a bowl of urine down a captured guard’s throat, or rape.

Villains are as conflicted as anyone else, otherwise how to explain that Harry climbs into the burning car containing his dead girlfriend, gives Pat a gentle kiss and waits for the car to explode and take him to a fiery grave. We’ve seen the softer side of Harry in flashes. He turns down the chance to bed a sex worker in the getaway lorry, doesn’t take advantage of the moll, and buries his face in the moll’s fur coat. The furthest he gets to expressing his feelings is to explain to Birdy that he was very happy with Pat. He’s almost – perish the thought – got a feminist side. And presumably it takes a lot for a tough gangster like him to open up to a woman, which explains why he takes her betrayal so badly.

The fact that he still kills her is somehow beside the point. As I said, gangsters are complex, witness the gay Richard Burton in Villain.

This is Ian MacShane (The Wild and the Willing, 1962) still in matinee idol mode, minus the gravitas and husky tones of John Wick (2014). Once the twists kick in, you look back and realize he’s stolen the film, a weaselly charmer, able to bend Harry (not that hard, mind you) to his will, which was to help him escape, lead him to the money and send him off to live happily ever after with Pat. Where Harry clearly believes in true love, Birdy has no moral scruples. Even with a beauty like Pat waiting for him, he’s happy to indulge in sex with the sex worker and help himself to the helpless moll. (MacShane was equally dubious in Villain).

Oliver Reed’s Thug we’ve seen countless times before, Oliver Reed’s Softie less so. Jill St John (Tony Rome, 1967) manages a British accent and proves herself capable of a better role than usual. Actors often say they build up a character from their walk. Watch Edward Woodward (The Wicker Man, 1973) for a classic example of it.

Douglas Hickox had essayed delicate romance via his debut Les Bicyclettes des Belsize (1968) and it’s to his credit that he touches on Harry’s sensitivity in such subtle fashion. Otherwise, some terrific standout sequences – Harry’s fist battering through the glass into the prisoner’s visiting room, the escape, the duel with motorcycle cops through a fog of washing strung out on lines, the final car chase.

Written by Alexander Jacobs (Point Blank, 1967) from the bestseller by Lawrence Henderson. Superb score by Stanley Myers.

Not quite in the league of Get Carter or Villain but not far short.