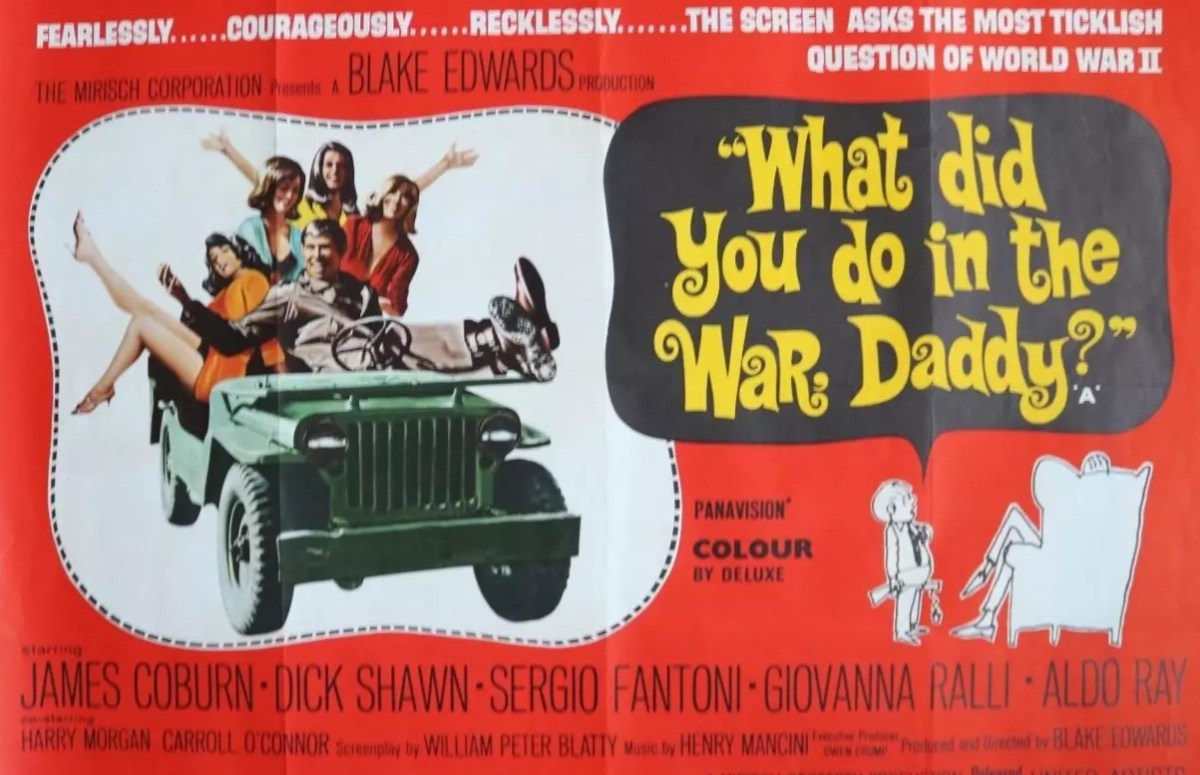

How on earth did James Coburn get mixed up in this mess? I’m assuming that having suddenly been elevated from supporting actor to top billing as a result of Our Man Flint (1966) he took the first job that came along that reflected his ideas about salary. Director Blake Edwards was, to some extent, at something of a loose end. United Artists had passed on The Great Race (1965) and another project with the director had fallen by the wayside. Apparently, this movie was the result of a question asked by his son. During World War Two, Edwards had served in the U.S. Coastguard which meant he did not see active service though did suffer a back injury. Writer William Peter Blatty (A Shot in the Dark, 1964) was too young for World War Two and though he joined the US Air Force he didn’t see active service either, being employed in the psychological warfare division.

So this exercise wasn’t going to be based on personal experience. The mid-1960s wouldn’t exactly lend itself to poking fun at war, although Vietnam was fair game.

You might have thought Coburn, on reading the script, would have realized he’s not much in the movie for the first 20 minutes or so and then is at the mercy of a bundle of subplots.

During the invasion of Sicily in 1943, stickler for discipline Captain Cash (Dick Shawn) is handed command of a disorganized unit headed by Lt Christian (James Coburn) and instructed to take a strategic village from the Germans. Turns out the enemy is long gone and the resident Italian soldiers, commanded by Capt Oppo (Sergio Fantoni), are only too happy to surrender as long as they can continue to enjoy la dolce vita which in this case involves an annual wine festival. Most of the early part of the picture revolves around getting Cash to loosen up, and after imbibing copious amounts of liquor and being seduced by the mayor’s daughter Gina (Giovanni Ralli) he relents.

There are only two obstacles to the merry party. Oppo objects to his girlfriend Gina being used as a makeweight to make Cash see things the Italian way and Cash’s boss General Bolt (Carroll O’Connor) asks to see proof of their success. So, since not a shot has been fired and they can’t boast of a camp full of Italian POWs, they decide to invent the proof and start filming phoney footage. Bolt reckons they need support and sends up reinforcements. Which is just as well because the Germans, either realizing what they’ve been missing or being nudged back into action, decide to reappear. And given the slovenly chaotic opposition it’s not hard for them to re-take control of the town which results in Cash hiding out in drag.

Theoretically, it’s a reasonable idea. There’s been no shortage of swindlers or con-men or black marketeers in war movies – think James Garner in The Great Escape (1963) and The Americanization of Emily (1964) – and various armies have been filled with shysters ranging from Sgt Bilko to the shifty recruits in British films up to all sorts of wheezes or doing their best to stay out of the line of fire.

But once the point has been made that it’s better to make love not war and drink as much wine as possible and become friends with the enemy, the point is made over and over again. There isn’t a single joke that isn’t belaboured and not many laffs to begin with. Going over-the-top is fine for slapstick like The Great Race but it doesn’t work here.

James Coburn has too little to do and Dick Shawn (A Very Special Favor, 1965) too much. Giovanni Ralli (Deadfall, 1968) and Sergio Fantoni (Hornet’s Nest, 1970 ) are wasted. Carroll O’Connor (Warning Shot, 1966) is the pick of a supporting cast that includes Aldo Ray (The Power, 1968) and Harry Morgan (The Mountain Road, 1960) but that’s only because he has a clever reversal of a role as a general who wants to be treated as an individual.

I should point out this has something of a cult following but I won’t be joining the fan club.

Must have seemed a good idea at the time.