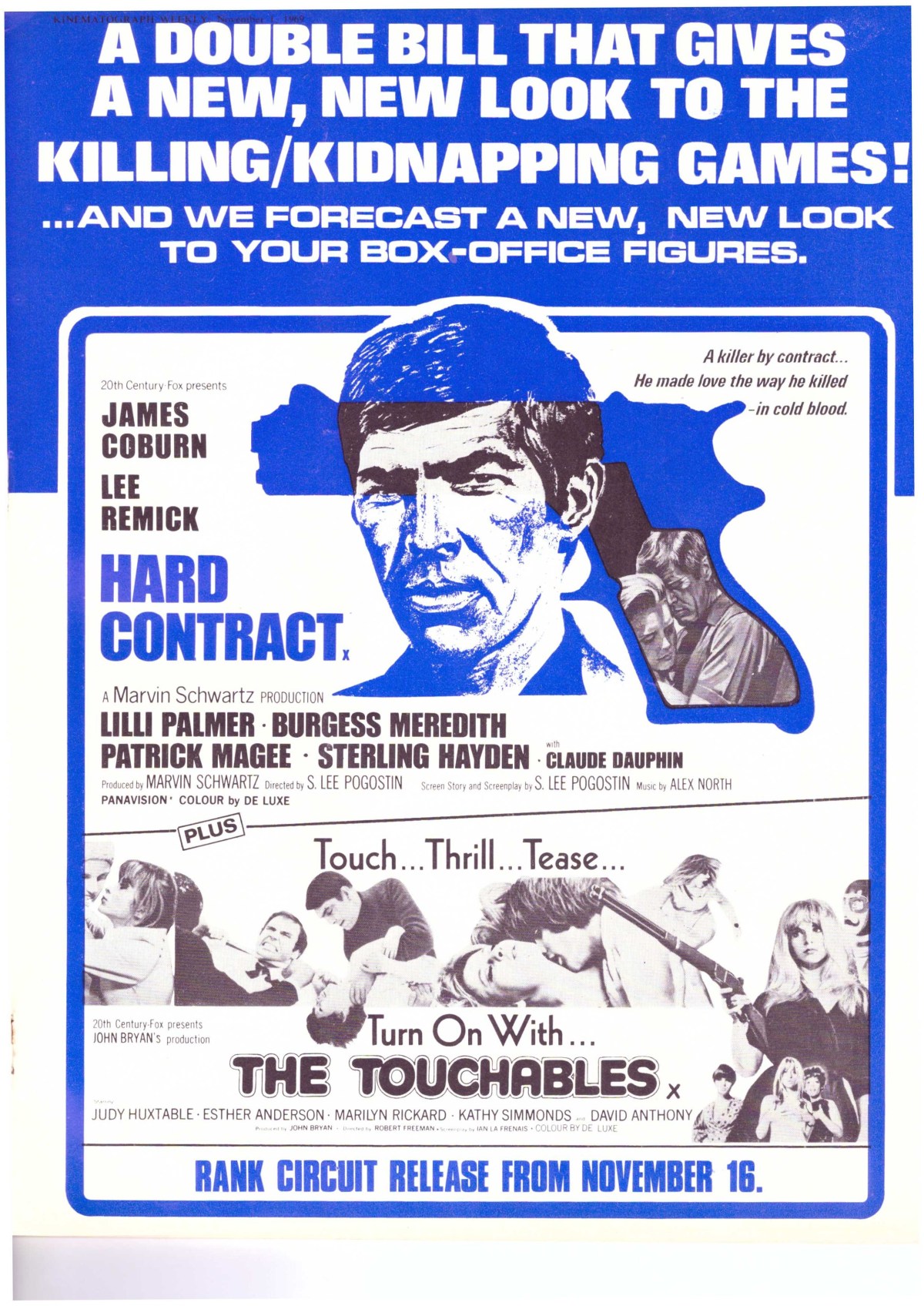

A hitman movie that verges on the existential is always going to be intriguing. Stone cold killer John Cunningham (James Coburn) manages to keep the world at a distance until he runs into the vibrant Sheila (Lee Remick) in Spain. The film is a curiosity of an admittedly small genre dominated by such disparate offerings as The Killers (1946 and 1964), Yojimbo (1961), Le Samourai (1967) and Stiletto (1969) in that although Cunningham does bump people off you never see the violence. We’ve come to expect hitmen to be introspective, but there’s never been anyone as closed-off as Cunningham. No romance in his life, only hookers, no apparent depth, in fact we learn very little about him.

He only runs into Sheila because for a laugh she pretends to be a sex worker. In reality she’s a wealthy divorced socialite running with a fast set that include Adrianne (Lili Palmer) and ex-Nazi Alexi (Patrick Magee) whom she loves to taunt but whose contacts allow Cunningham to be effectively stalked. And as unsavoury that might be from today’s perspective, it sheds light both on her power and whimsicality.

There’s an unusual background. Amid the extensive jet-setting in Torremolinos, Madrid and Tangiers, there are reality counterpoints, reflecting the issues of the decade – violent demonstrations with police using water cannon to control the crowds, the American elections and discussions about God, world hunger, terrorism and population growth.

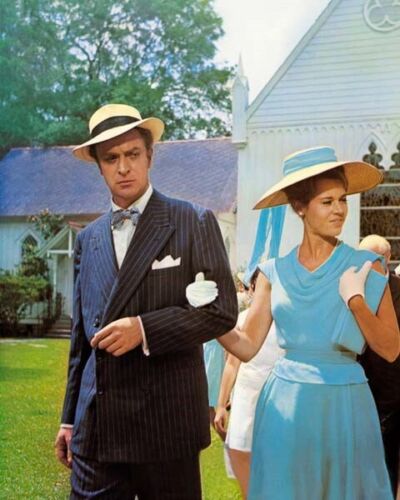

No doubt the script is wordy, but there’s hardly a word that doesn’t challenge convention. It’s steeped in amorality – a touchstone of the decade – good only occurs “when evil takes a rest” and the world is “immune to murder.” And you certainly get the impression that the rich can confront anything because, not having to live in the ordinary world, they can get away with it. Conversely, this is also one of those films where you wonder who did the wardrobe (Gladys de Segonzac, since you ask, who ran fashion house Schiaparelli in the 1950s) because not only does Sheila sport clothes that would have delighted Audrey Hepburn but Cunningham gets away with wearing a white jacket.

And if Korean vet Cunningham is enigmatic, the insomniac Sheila is cut from a similar cloth, and while a potential source for redemption is as likely to have sex with a casual pickup in a filthy alley. The story does not go quite the way you would expect – Cunningham’s growing dissatisfaction with his profession revealed when he can’t perform in a Brussels brothel. And his mindset allows him to consider mass murder as a solution to an emotional problem he cannot solve.

At core, of course, is whether once Cunningham’s emotional defenses are breached he can continue as a hitman, and whether Sheila can accept his profession. The stakes rise when it transpires that (like Stiletto made the same year) retirement is not an option.

And for all the seriousness on show, there are some imaginative moments of hilarity – Cunningham’s idea of a love song is “To the Shores of Tripoli” and Adrianne proves determinedly indiscreet. In keeping with the paranoia cycle that was about to explode, you never find out why people are being murdered, or even who they are, far less the group which his boss Ramsay (Burgess Meredith) is fronting.

Far removed from the Derek Flint persona that had turned him into a star, James Coburn delved deeper into the amoral territory he had previously explored in Waterhole 3 (1967). Lee Remick (The Detective, 1968) is sheer madcap delight even when espousing her odd takes on philosophy. Lili Palmer (The Counterfeit Traitor, 1962), who by this point in her career was usually the wife or girlfriend, creates a very original character. Veteran Sterling Hayden had only made one film (Dr Strangelove, 1964) during the decade and is excellent as a contemplative retired hitman. Patrick Magee (The Skull, 1965) gives another of his tight-lipped performances. Karen Black (Easy Rider, 1969) has a small role as does Sabine Sun (The Sicilian Clan, 1969).

This marked both the debut and the demise of the directorial career of S. Lee Pogostin, best known at this point as the screenwriter of Pressure Point (1962) and Synanon (1965). In terms of argument over issues it stands comparison with Pressure Point but without that film’s intensity.

I remember being baffled by the picture when it came out and I was a teenager because the action I believed I had been promised never materialized but otherwise I could remember little about it so now it appears as an interesting antidote to the mindless action pictures.