Unusually for an Otto Preminger project, this took an unconscionably long time to get off the ground, given he had purchased rights to the bestseller by Evelyn Piper which had been published in 1957. The first problem was that no one could lick the screenplay. Getting first bite was Ira Levin (Rosemary’s Baby, 1967), followed by “wholesale doctoring” by Dalton Trumbo (Exodus, 1960) who delivered a “polished script.” But that failed to satisfy the director either and triggered further attempts by Charles Eastman (Little Fauss and Big Halsy, 1970) and Arthur Kopit (Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mummy’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feeling So Sad, 1967). But nobody seemed able to come up with a satisfactory job. The book had been set in New York as had the various subsequent screenplays. The solution appeared to be to shift the location some 3,000 miles to London. Penelope Mortimer (The Pumpkin Eater, 1964) wrote a draft but ended up having a fight with Preminger and withdrew and the project was completed by her husband John Mortimer (John and Mary, 1969).

The Levin screenplay was dismissed as being too faithful to the book, the kidnapper in this instance turning out to be a former teacher who was childless and afflicted with “menopausal psychosis,” a character Preminger found weak and uninteresting. Trumbo changed the villain into a wealthy woman, not just childless but judged unfit to adopt, an approach the director deemed “very theatrical and wrong.” The Kopit and Eastman versions offered no better solution. “I almost gave up Bunny Lake,” admitted Preminger, “because while working in the script I realized that women would not like the film…because they are afraid of all situations in which a child is in danger.” After considering transplanting the story to Paris, Preminger finally settled on London, and hired the Mortimers whose villain brought the picture a 2new dimension.”

Until now, and in keeping with the original novel, Newhouse, while assisting in the investigation, had been a psychiatrist. In the hands of the Mortimers he now morphed into a police inspector. Wilson who had been Newhouse’s quite respectable friend turned into a drunken reprobate. At this point the heroine’s name remained Blanche as in the book. There was one other significant element that changed between the initial Mortimer script and the final shooting script: at the start of the film the Ann and Steven were shown reacting as if the child was there, whereas when the movie went before camera the question of the child’s existence remained in doubt. Penelope Mortimer dropped out when, summoned with her husband to Honolulu where Preminger was filming In Harm’s Way, she was roundly ignored.

Filming was originally scheduled to slip in between Anatomy of a Murder (1959) and Exodus (1960) with a budget set at $2 million. But something always seemed to get in the way. Occasionally it was a bigger project. After Columbia announced filming was scheduled for 1961, Bunny Lake was pushed back to spring 1962 to permit the filming of Advise and Consent (1961). Then The Cardinal (1962) took precedence but only to the extent of shifting the Bunny project till later that year. Then it was set to be completed by fall 1963. Further cause of delay was the decision to accommodate the pregnancy of that Lee Remick who had signed for the leading female role. But when she was ready to go, Preminger was not and she fell out of the equation.

At one point, fearful of his schedule becoming too crowded – filled with expensive projects like The Cardinal and In Harm’s Way (1965) – Preminger had tried to wriggle out of the directorial commitment, planning to limit his involvement to producing only, but studio Columbia would not accept this. Preminger was in considerable demand, like a major movie star contracted to deals with rival studios, in 1961 for three pictures with United Artists and four for Columbia and by 1965 adding into the mix a seven-picture deal with Paramount, and most of these big pictures, leaving little time for a relatively low-budget – by his standards – picture.

Finally, Bunny Lake received the green light with filming beginning in London on April 9, 1965. Unusually, the movie was shot entirely on location, the director expressing a “yen for realistic on the spot” filming in a dozen places including a pub, the Cunard office and Scotland Yard. A school in Hampstead doubled for the nursery, the mews flat was found just behind Trafalgar Square. He was quick to point this was not a matter of economy. “What you save in studio (time) you spend in other ways. But I think it leads to more urgent film-making.” Somewhat surprisingly, he aimed to shoot in black-and-white, colour now being predominant except for low-budget movies and those wishing to take advantage of black-and-white world War Two newsreel footage as was the case with his previous picture In Harm’s Way.

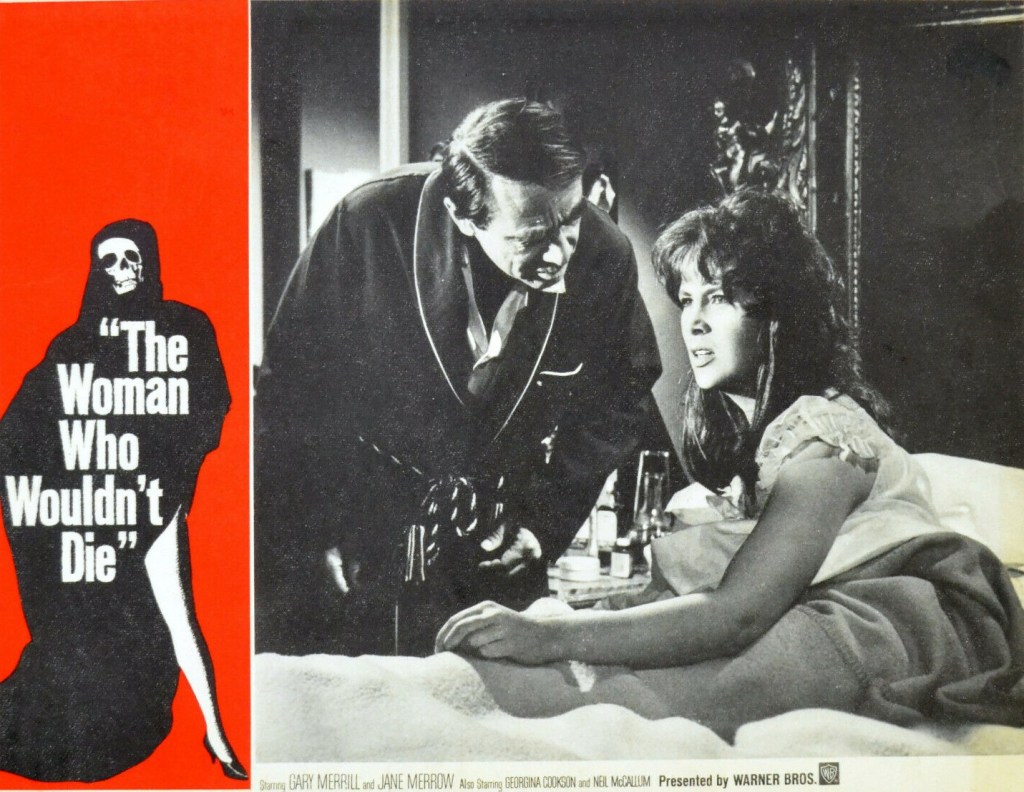

Carolyn Lynley (The Pleasure Seekers, 1964) was given the lead with Keir Dullea (David and Lisa, 1962) in the pivotal role of her brother. Neither could be considered a big star although Lynley had the second female lead in The Cardinal and moved up the credit rankings to female lead in the low-budget Shock Treatment (1964). But she was such a hot prospect Preminger in 1965 signed her to a four-picture deal although this was not exclusive as she also had contracts with Twentieth Century Fox and Columbia. Dullea was potentially a better prospect, picking up some acting kudos for David and Lisa, the designated star of that picture and The Thin Red Line (1964) but only second lead for Mail Order Bride (1963) and the Italian-made The Naked Hours (1963).

Although some decades away from his Hollywood box office prime, the casting of Oscar-winner and five-time nominee Laurence Olivier (Spartacus, 1960) was something of a coup, although he was only hired because another actor proved too expensive. Other parts were filled by actors experienced in the Preminger school of film-making, Martita Hunt from The Fan (1949)- and Bonjour Tristesse (1958), Victor Maddern (Saint Joan, 1958) and David Oxley (Saint Joan and Bonjour Tristesse).

The first day’s shooting was in a television studio to capture the newsreader and pop group The Zombies which the content of the show shown in the pub on television. Contrary to depictions of Preminger as a martinet on set, he was keen in rehearsals to “put everyone at ease” although he emphasised the need for “slow, thoughtful diction.” The famous Preminger wrath came down heavily on personnel failing to carry out their job correctly. But he accepted Olivier’s decision to omit a particular phrase. He was specific about the look he wished to achieve, required high contrast black-and-white cinematography while nothing was to be done “to enhance Carol Lynley’s beauty: instead…to deepen her features, bring out her emotions.”

And he was determined to get what he wanted, 18 takes required to complete a lengthy tracking shot that flows Inspector Newhouse (Laurence Olivier) and Miss Smollett (Anna Massey) as they negotiate a passage through a group of noisy children in a classroom and then across a hall. Accepting Lynley’s difficulty in expressing the pain of losing a child, he instructed her to forget about subtext and play the moment. However, 14 takes of a scene between Lynley and Olivier was too much for the actress but she was comforted when Preminger told her the famous actor was the problem not her. But on another occasion, Preminger ended up giving her an almost line for line reading of how he wanted the scene played. The only way he got what he wanted was to reduce her to “sobbing uncontrollably” and then start the camera rolling.

Without question, Keir Dullea came off first. “He would humiliate you, he would scream at you…his dripping sarcasm was the worst of it,” recalled Dullea. “I was always very prepared in terms of knowing my lines…but the stress, there was some action where I was supposed to put a glass down or pick up a glass” that Dullea kept getting wrong. In face of what he deemed incompetence, Preminger accused him of being “an actor who can’t even remember a line and if heremembers a line he can’t remember an action…what, you can’t do these two things at the same time.” In the end Dullea faked a nervous breakdown and after than “he never screamed at me again.”

Olivier would occasionally coming to rescue, persuading the director to ease off and “stop screaming at the children.” Olivier found Preminger such a bully that it “almost put me off his Carmen Jones, which I found an inspired piece of work…It’s a miracle it came from such a heavy-handed egotist.” On the other hand Noel coward, who played the landlord Wilson, believed Preminger an excellent director.

Preminger spun his marketing on a similar gimmick to that utilised by Alfred Hitchcock for Psycho (1960) in preventing the public from entering once the movie had started. To make this more dramatic, he had clocks installed in the lobbies of theaters that counted down the length of the performance and a sign that stated “nobody admitted while the clock is ticking.” Preminger was credited with coming up with a longer tagline for the advertisements: “Not even Alfred Hitchcock will be admitted after the film has started.”

The only problem was Return from the Ashes, released at the same time, had adopted a similar marketing ruse, nobody admitted “after Fabi enters the bath.” Despite this, Preminger went hell-for-leather for this marketing trick, to the extent of adding a rider to exhibitor standard contracts to that effect, not a problem in more sophisticated cities where by now patrons had become accustomed to turning up for a picture’s announced start time but a problem in smaller towns and cities where the whole point of continuous programme (i.e. no break between one film and another) was that moviegoers could walk in whenever they liked.

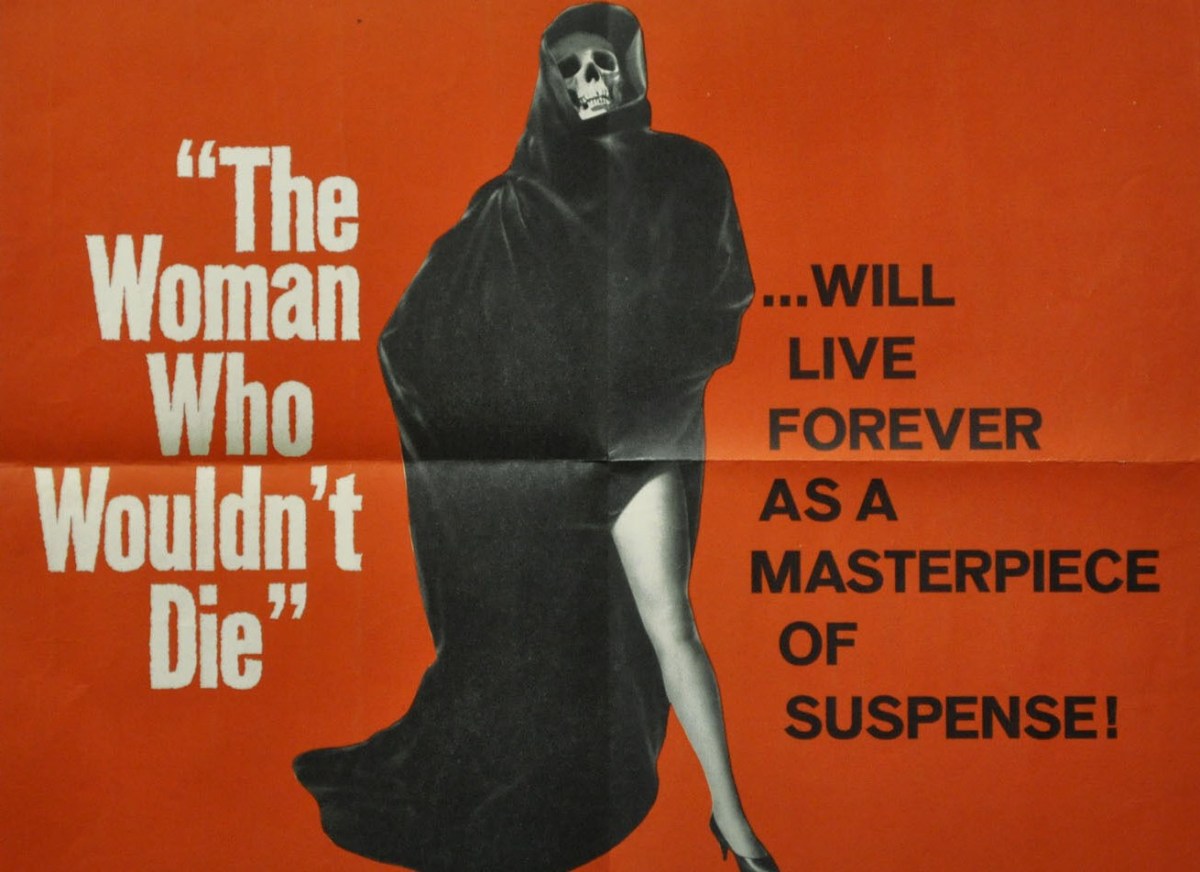

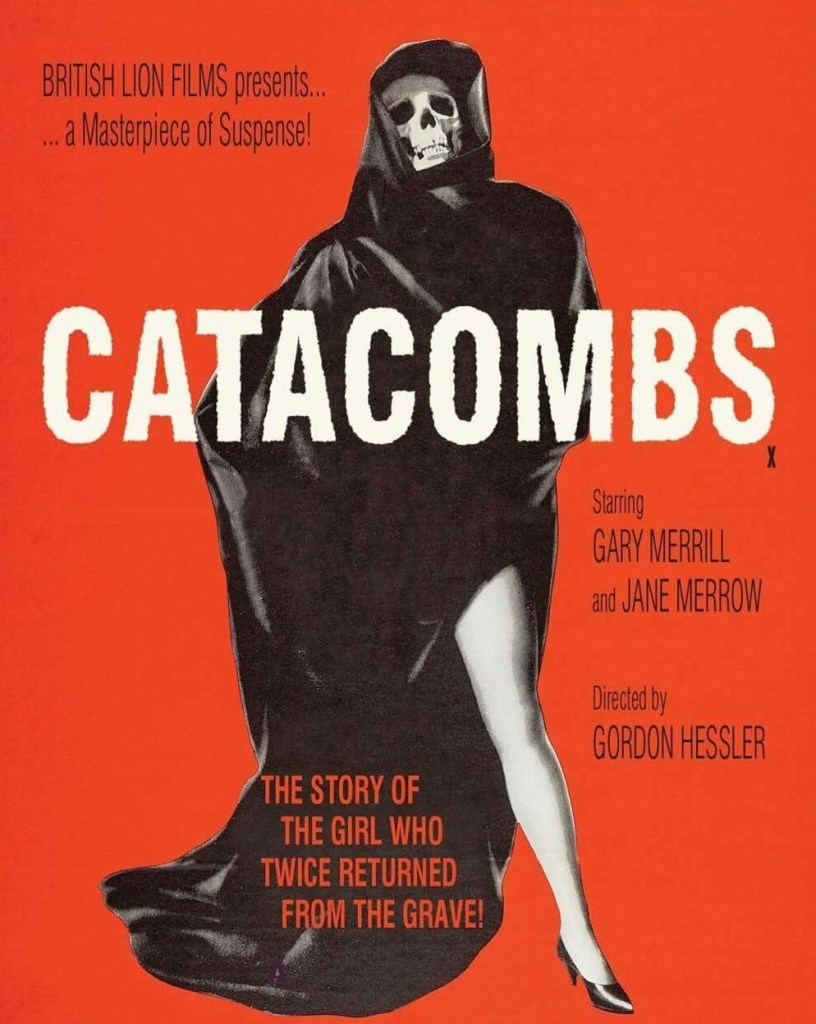

The whole tone of the marketing did not meet the approval of two important segments of the greater movie community. The National Association of Theater Owners opined that the marketing campaign was weak and were astonished to learn that there was nothing Columbia could so about it – Preminger had advertising-publicity approval. Allowing that some of the advertising images for Preminger pictures, courtesy of designer Saul Bass – The Man with the Golden Arm (1953), Anatomy of a Murder, Exodus etc – were among the most famous in Hollywood history, it would appear Preminger knew what he was doing. But, in fact, although the Saul Bass credit sequence showing pieces of newspaper being torn away made sense in the framework of the picture, the idea was not so effective taken out of that context.

Not intentionally, perhaps, Preminger also riled the critics, deciding that to “preserve the secrecy of the surprise ending,” the movie would open without the normal advance screenings for reviewers. Such action was more likely to set alarm bells ringing, it being a standard assumption among critics that the only films that went down this route were stinkers. From a practical point-of-view it also ensured that marketing was undercut since the lack of timed reviews denied the picture an essential promotional tool.

Finally, the movie ended up in a war with the censors. Many states in the U.S. had their own censors. Columbia objected to having to wait on the say-so of a local censor – in this case Kansas – before being able to release a movie. And for any release to be delayed if there was any nit-picking by the censor, especially as this movie had an undercurrent of incest. So Columbia refused to conform and failed to submit Bunny Lake Is Missing to the Kansas censors. After being promptly banned for such arrogance, Columbia objected again and the case went to the Kansas State Supreme Court which judged that the censor was unconstitutional. That resulted in the censors losing their jobs when the board was abandoned and the movie entering release a good while after its initial opening dates.

Although it made no impact at the Oscars, Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris picked it as one the year’s ten best and it was nominated for cinematography and art direction at the Baftas. The film was a flop, failing to return even $1 million in rentals at the U.S. box office. In fact it probably made more when it was sold to ABC TV for around $800,000.

SOURCES: Chris Fujiwara, The World and Its Double, The Life and Work of Otto Preminger, p330-342; (Faber and Faber, 2008) “Trends,” Variety, January 14, 1959, p30; “Ira Levin Pacted by Preminger for Bunny,” Variety, September 2, 1959, p2; “Col Primed To Start ½ Dozen Prods,” Variety, April 5, 1961, p3; “Otto Preminger Views Film Festivals As Important Marketplaces,” Box Office, May 1, 1961, p11; “Trumbo May Script for UA,” Variety, May 31, 1961, p5; “Bunny Lake Delayed,” Variety, June 7, 1961, p18; “Preminger Postpones One,” Box Office, June 12, 1961, p13; “Otto Preminger to Film Cardinal for Col,” Box Office, August 7, 1961, -10; “Otto Preminger Is Guest of Soviet Film Makers,” Box Office , May 14, 1962, pE-4; “Two Writers Signed,” Box Office, August 6, 1962, pSW-3; “Preminger,” Variety, September 12, 1962, p15; “Preminger’s New Rap at Costly U.S. Distribution,” Variety, October 10, 1962, p7; “Preminger Gets Rights to Hurry Sundown,” Box Office, November 23, 1964, p9; “Prem’s Next in London,” Variety, January 13, 1965, p18; “Preminger Signs Actress for Four More Pictures,” Box Office, February 8, 1965, pW-3; “Advertisement,” Variety, April 7, 1965, p1; “Preminger-Paramount Pact Calls for 7 Films,” Box Office, April 26, 1965, p7; “100% Location for Bunny,” Variety, May 5, 1965, p29; “Not Even Hitch,” Variety, September 1, 1965, p4; “Preminger’s Nix on Pre-Opening Critics,” Variety, September 22, 1965, p16; “2 Pix Enforce Entrance Time on Ticket Buyers,” Variety, September 29, 1965, p5; “Time Rules Are Set for Bunny Shows,” Box Office, October 4, 1965, p13; “Preminger’s Promotional Prerogative,” Variety, October 27, 1965, p13; “Clock for Bunny Lake,” Box Office, November 8, 1965, p2; “Village Voice Vocal on Bests,” Variety, January 26, 1966, p4; “Col Kayos Kansas Censoring,” Variety, August 3, 1966, p5.