Will easily hook a contemporary audience. Especially stylish in its narrative choices and visually carries a punch. Slips cleverly between the two standard tropes of the heist picture – the theft where we know in advance what the target is, e.g. Topkapi (1964) and the one where we’re kept in the dark about what exactly is going on for some time e.g Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round (1966). Here, director Cliff Owen teases audiences from the start. The sizzling opening sequence involving two explosions and a flame-thrower aren’t rehearsals for the heist but a dry run for the escape.

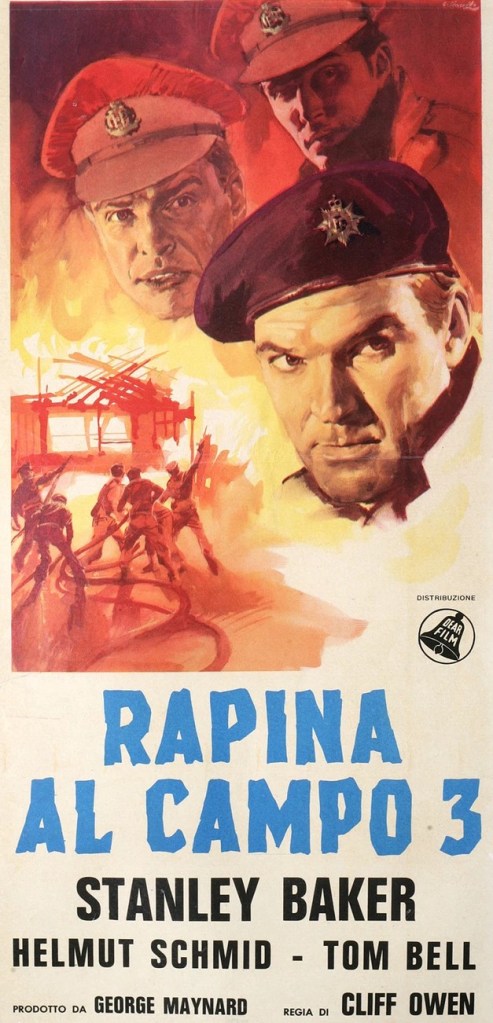

All we know for about half the picture is that Turpin (Stanley Baker), a former Captain bearing a grudge against the Army, wartime Polish buddy Swavek (Helmut Schmid) and young gun Fenner (Tom Bell) who’s too fond of the booze, are, courtesy of the opening sequence, up to no good. Once they don Army uniforms, but without any relevant papers, on the eve of the British invasion of Suez in 1956, it’s clear that for some reason an Army barracks is their target.

Bureaucracy both works in their favor and against them. A guard at the gate is easily duped into thinking that office error accounts for the lack of paperwork as they drive an Army truck into the establishment. But then bureaucracy hampers their efforts. For standing around too idly, Fenner is forced into a spot of pot-washing. When Turpin fakes an illness, he’s commandeered by a male nurse who refuses to let him leave until he’s been examined. Attempts to steal a stretcher, essential it transpires to their plan, are thwarted.

Turpin is forced to constantly revise his plans in the face of unexpected adversity and the realization that Fenner is something of a liability. Integrating themselves into the Army base is not as easy as it might appear because everyone has designated duties and people without purpose stand out.

Turns out, pretending to be Military Police, they’re planning to make off with a £100,000 payroll (£2.1 million in today’s money). Their plan, once it kicks in, is exceptionally clever and works well.

The stretcher element, however, causes a problem and soon both Army personnel and cops are on their tail. But they’re one step ahead. Even when they appear to be cornered, don’t forget they’ve got that flame-thrower tucked away for emergencies.

The heist itself, while a clever enough ruse and crackling with suspense, is only the bridge between the tension-filled sections before and after, the build-up and the chase. Part of the fun is that what can go wrong comes from the most unexpected sources.

Although Stanley Baker had headlined a few movies this was a breakthrough in screen persona, the tough guy cool under pressure with a meticulous understand of detail that would be shown to better effect in the likes of Zulu (1964). He’d return to the scene of crime in Robbery (1967) and Perfect Friday (1970). Tom Bell (Lock up Your Daughters, 1969) impresses as the nervy unreliable sidekick, and while German actor Helmud Schid (The Salzburg Connection, 1972) has less to do.

You certainly won’t miss Patrick Magee (Zulu) as a terrifying sergeant-major but you’ll need to be quick to spot the debuts of Rodney Bewes (The Likely Lads TV series, 1964-1966) and character actor Glynn Edwards (Zulu). And you might think it worth mentioning that future director Nicolas Roeg (Don’t Look Now, 1973) had a hand in the screenplay credited to Paul Ryder (A Matter of Choice, 1963)

This is a no-frills exercise, with romance and sex excised so no sub-plot to get in the way. Cliff Owen (The Vengeance of She, 1968) sticks to the knitting.

Crisply told.