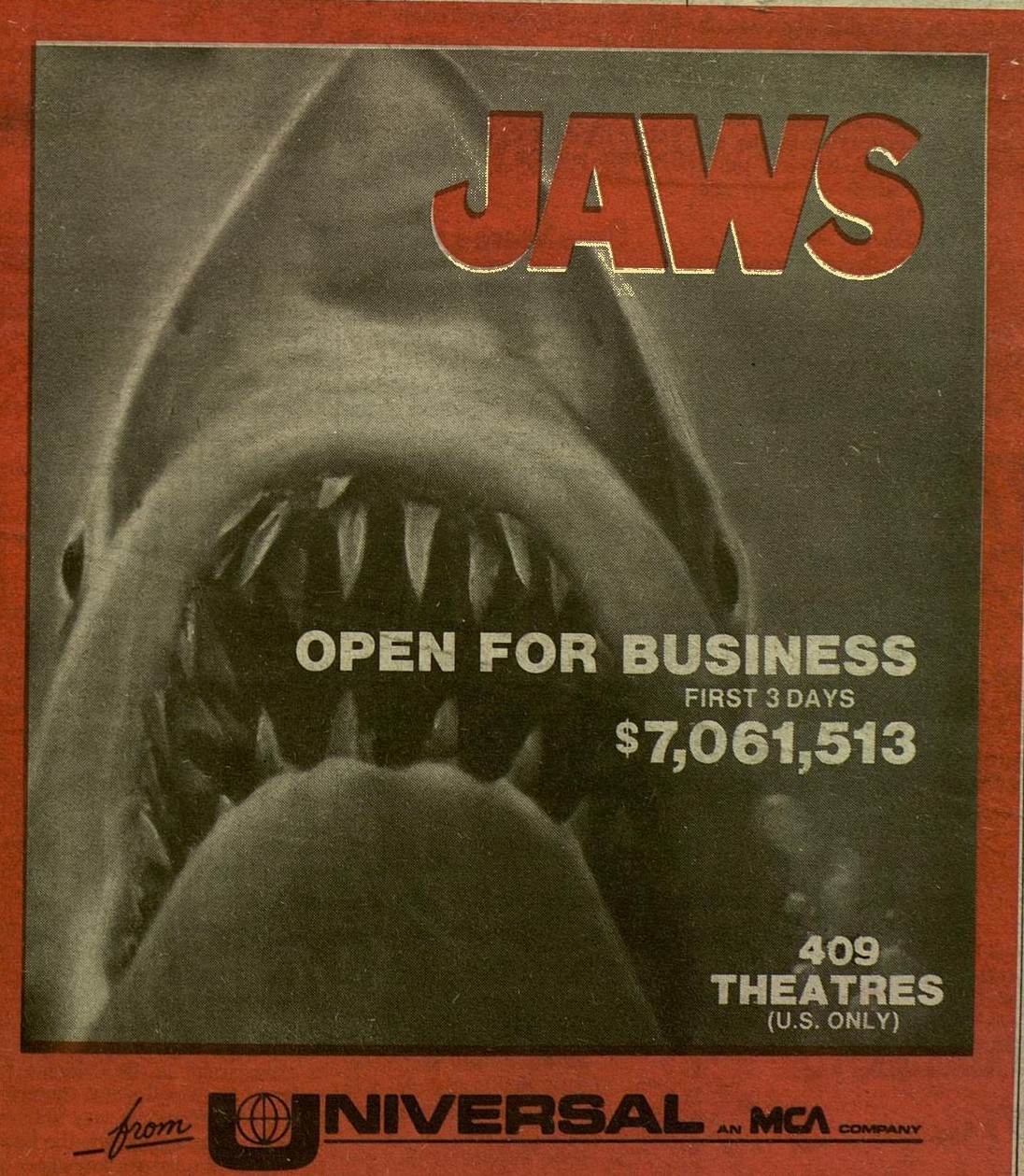

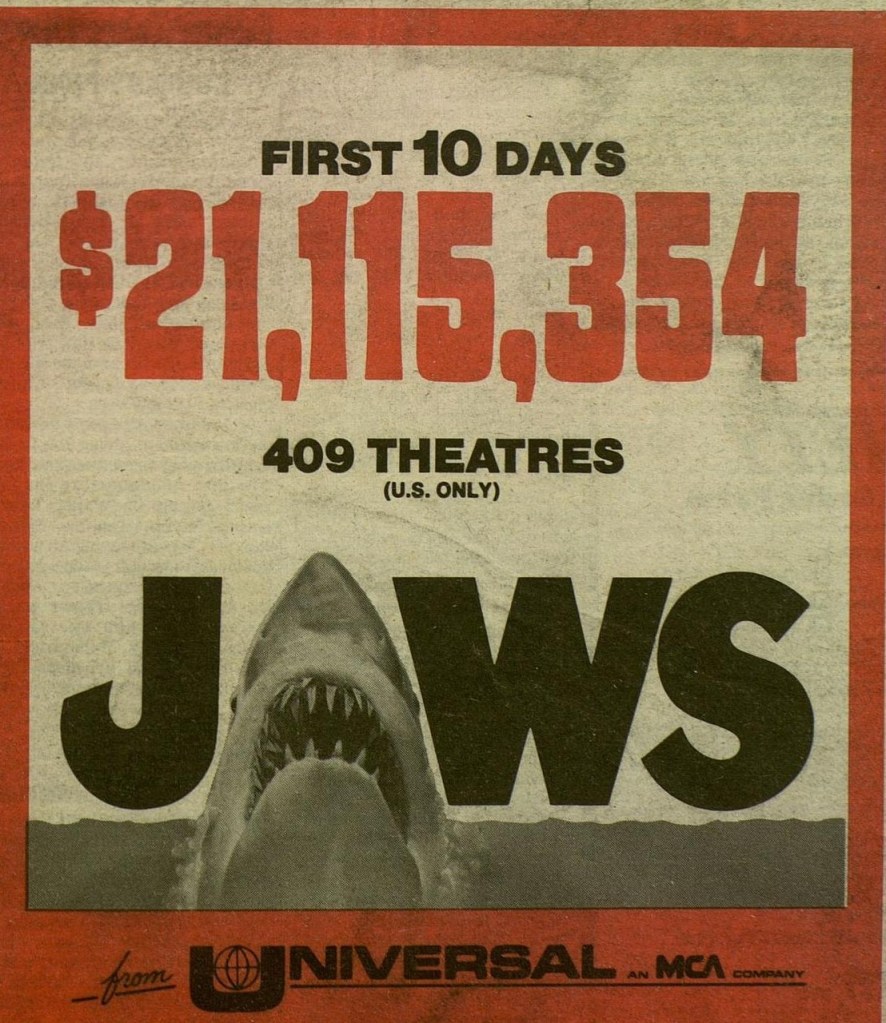

Given the surprising success of the reissue of Jaws this weekend – it came in second at the U.S. ticket wickets ahead of such new films as The Roses and Caught Stealing – I thought you might like a second look (or a first one) at exactly how Universal created box office history. And it was not the way you would expect. It did not follow the template set out by previous juggernauts.

Naturally, the hoopla surrounding the 50th anniversary of Jaws concentrates on the budget overruns, director Steven Spielberg’s problems and the mechanical shark, and no one gives a hoot about the most important aspect of the picture – the box office. Sure, it’s always mentioned in passing, because otherwise the movie would have had little impact on pop culture, the driving force of the water cooler effect when so many people see the same movie at the same time it drives word-of-mouth into the stellar regions.

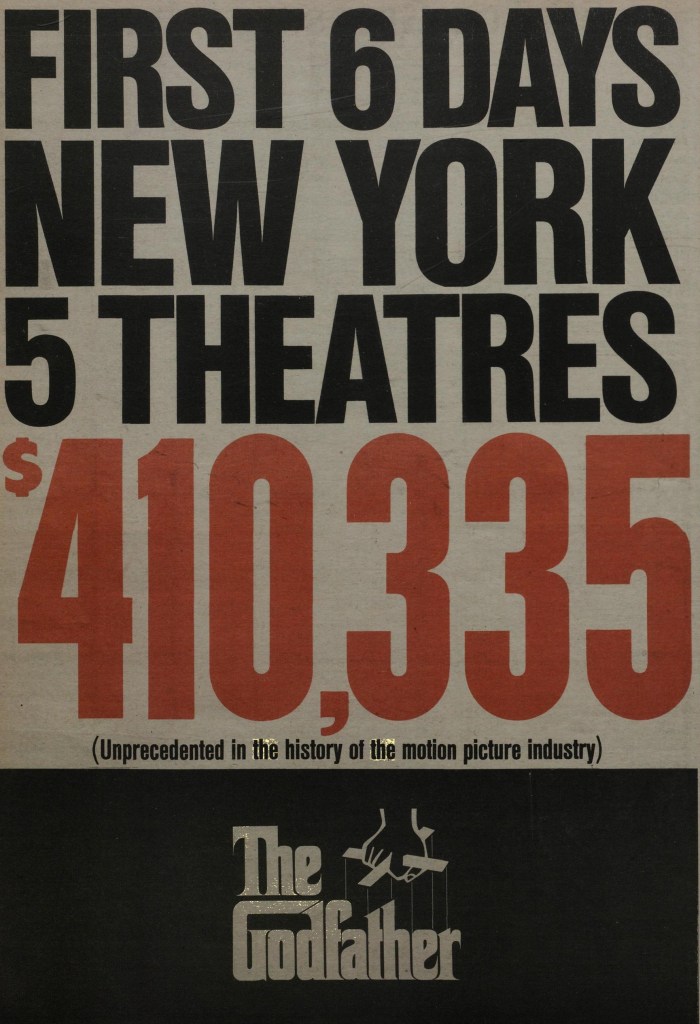

What is little known is how Jaws changed the release system forever. Even The Godfather (1972), its predecessor in topping the box office firmament, while spreading the goodies amongst nabes and the showcase houses did not ignore first run. In fact, for The Godfather Paramount used five New York first run houses – the 1025-seat Orpheum, 1175-seat State I, 1174-seat State II, 599-seat Cine and 588-seat Tower East – to create a pre-emptive strike. This quintet screened the movie exclusively for the first week, permitting the studio to trumpet the record-breaking results.

The other 350-odd cinemas had to wait a further week to get their hands on the gangster saga.

For Jaws, on the other hand, Universal completely froze out New York first run. Not a single first run house was given access to the picture on its initial release on this weekend 50 years ago.

Instead, in New York, Universal went down the showcase route and clocked up just over $1 million in the first three days at 46 cinemas. Prior to Jaws, the only pictures that would open first in showcase in New York and ignore that city’s vibrant first run were those that first run would most likely have declined to show.

With Jaws, across the country Universal was as ruthless in squeezing out first run if it could make a better deal in the nabes and drive-ins. So while Jaws set house records at all the first run houses that were deemed up to standard, it also creamed the nabes and drive ins. Significantly, not all the first run houses chosen would have been the first choice of most studios for a major picture. You wouldn’t have expected this behemoth to end up at the 925-seat Gopher in Minneapolis where it took in $47,000. Similarly, the 900-seat Charles in Boston ($55,000 take) would not have been your first choice (and it’s worth noting that it was only in this city that the movie did not top the week, beaten into second place by Woody Allen’s Love and Death at the 525-seat Cheri Three).

By and large, Universal picked off those first run cinemas that were so delighted to be asked they agreed to the tough terms – a 90/10 split in the studio’s favor and a 12-week run.

Other first run destinations included the 800-seat Cooper in Denver ($53,000 for openers), the 1670-seat Coliseum in San Francisco ($68,000), the 900-seat Southgate I and 550-seat Town Center II in Portland ($55,000 total), the 1836-seat Gateway in Pittsburgh ($70,000) and the 1287-seat Midland in Kansas City ($55,000). In these cities, the premiere outing was restricted to first run.

But while in Chicago the 1126-seat United Artists hauled in $116,000 in the opener, Universal played it canny by screening it simultaneously at four other nabes which brought in another $260,000. It was the same in Cleveland where the 455-seat Severance II was the only first run house among the five cinemas that hoovered up a total of $84,000. The first run 500-seat Goldman in Philadelphia was the only first run location among the total of 15 cinemas that knocked up $312,000.

Elsewhere, echoing the New York approach, first run cinemas were frozen out in Detroit, Buffalo and San Francisco. In Detroit seven nabes gobbled up $350,000, in Buffalo a deuce of nabes snatched $50,000, in San Francisco a trio set about $75,000.

We’ve all seen movies driven to opening weekend box office heights on the back of heavy advertising or hyperbole only to take a dive in the second week. And the fact that Universal was not making an “event” out of its movie by restricting it to first run meant that the sophomore weekend could easily have brought disaster.

Instead, receipts at virtually all the cinemas either beat the first week or fell only fractionally below. The opening weekend appeared to set the tone, every successive day better than the previous one.

Universal immediately set its sights on taking down The Godfather and began posting weekly advertisements in the trade papers hyping its performance at the box office. But in nudging first run out of the equation, it triggered the slow decline of first run houses.

Tomorrow, you can catch on my article that sunk many of the other myths surrounding Jaws, “Behind the Scenes: Exploding The Myth of Jaws.”

SOURCE: Variety.