You don’t just waltz into Hollywood and start churning out classics like Some Like it Hot (1959), The Magnificent Seven (1960), West Side Story (1961) and The Great Escape (1963). Usually, there’s a long apprenticeship, especially for a producer. Walter Mirisch spent nearly a decade at the B-picture coalface. And before that a year as a gofer, working his way up in the business, but on one of the smallest rungs of all, at Monogram.

Born in 1921, the of a Polish immigrant tailor specializing in custom-made garments, one of whose customers was George Skouras, owner of a cinema chain, Walter, not surprisingly in the Hollywood Golden Age, started out an even lower rung, as an usher in the State Theater in Jersey City, owned by Skouras, an hour’s commute from his home in the Bronx, earning 25 cents an hour. He was quickly promoted to ticket checker.

His older brother Harold was a film booker, receiving an education in negotiation, and then as a cinema manager in Milwaukee flexed his entrepreneurial muscles by starting a concession company. After the family moved to Milwaukee, Walter attended the University of Wisconsin and then Harvard Business School. Physically unfit for active duty during the war, he worked for Lockheed in Los Angeles on its aircraft program in an administrative capacity.

While Harold was a highflyer at RKO, acting as chief buyer and then managing its cinema chain, Walter entered at a lower level in 1946 as a general assistant to Steve Broidy, boss of Monogram, maker of B-pictures of the series variety – Charlie Chan, The Bowery Boys, Joe Palooka, shot within eight days and at budgets under $100,000.

After badgering Broidy for a bigger opportunity, he was granted permission to hunt for a property he could produce. For $500 he found a Ring Lardner short story about a boxer, but Broidy felt the main character was unsympathetic. Stanley Kramer did not and snapped it up to make Champion (1949).

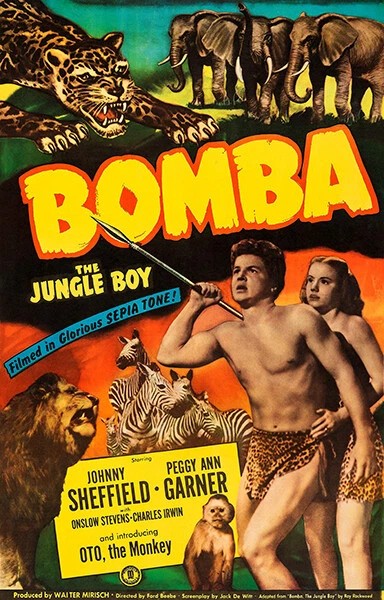

Walter’s first ventures were in film noir. Fall Guy (1947), based on a story by Cornell Woolrich, made for $83,000, broke even. I Wouldn’t Be In Your Shoes (1948) followed, from a Woolrich novel but there was a drawback to being a producer. He was taken off the payroll and his $2,500 producer’s fee didn’t compensate for the loss of a $75 weekly salary. The answer was to invent his own series, ripping off the Tarzan pictures for Bomba the Jungle Boy (1949), starring Johnny Sheffield who had played Tarzan’s son and utilizing stock footage from Africa Speaks. Apart from his fee, Walter had a 50 per cent profit share.

For six years, these appeared at the rate of two a year, earning Walter a minimum of $5,000 and he soon branched out into other genres, sci fi like Flight to Mars (1951) and westerns such as Cavalry Scout (1951) and Fort Osage (1951), both starring B-movie stalwart Rod Cameron.

Monogram had decided to move upmarket with the introduction in 1951 of Allied Artists, its sales division run by Walter’s brother Harold, with Walter acting as an executive producer and other brother Marvin as treasurer, turning out solid B-picture-plus hits like Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954).

When the threat from television hit the B-picture market Allied went properly upscale, investing in William Wyler western Friendly Persuasion (1956) and Billy Wilder’s Love in the Afternoon (1957), both starring Gary Cooper. Their failure at the box office sent Monogram back to basics.

But the Mirisches wanted more of the big time. The three brothers turned to United Artists and negotiated a deal for that studio to finance four pictures a year, cover the brothers’ overhead and salaries and throw in a profit share. The Mirisch Company was born and their creative credit within the industry was so high – and the deals they offered, it has to be said, so advantageous to their creative partners – that soon they were scooping up big names like Wilder (he made his next eight pictures for Mirisch), William Wyler, Gary Cooper, Tony Curtis, Doris Day, Audrey Hepburn and Lana Turner. One of the first pictures announced was a remake of King Kong (1933). Wilder planned My Sister and I with Hepburn. John Sturges was attached to 633 Squadron. Doris Day would star in Roar Like A Dove and there were two-picture deals with Alan Ladd and Audie Murphy.

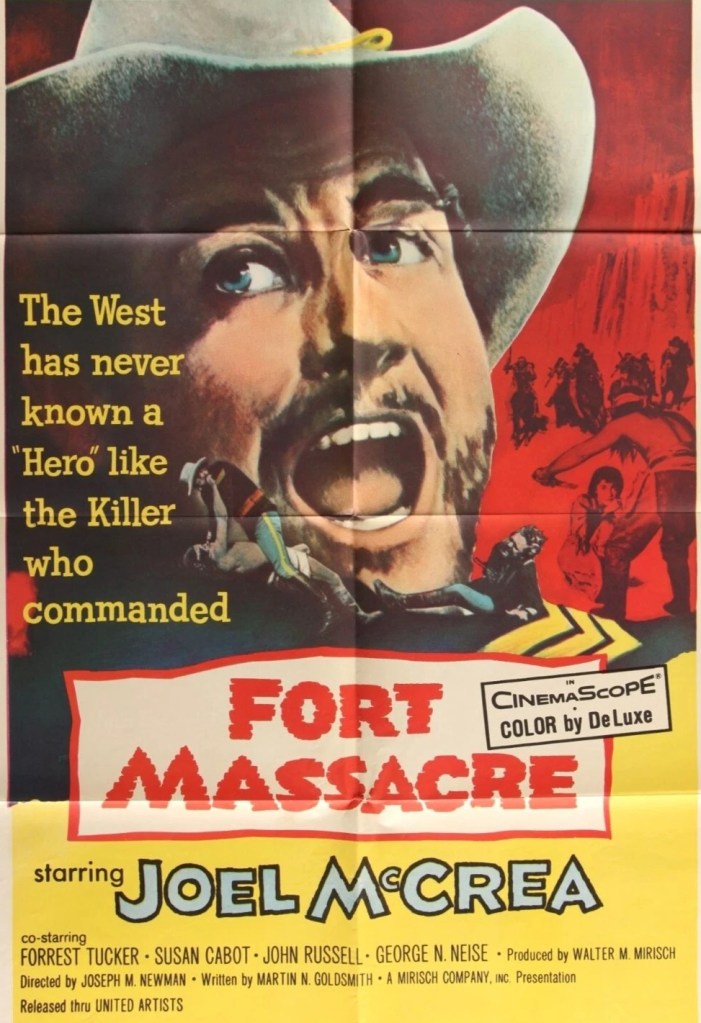

Their first two efforts didn’t break the budget bank, Fort Massacre (1958) starring Joel McCrea, and Man of the West (1958) headlined by Cooper, but neither were they hits. Hoping to provide ongoing financial sustenance, Walter turned to television, turning Wichita (1955) into the series Wichita Town (1959), and further television contributions were mooted for UA Playhouse but that and Peter Loves Mary and The Iron Horseman failed.

Movies proved a better bet and Walter struck gold with the third picture in the Mirisch-UA deal, Some Like it Hot (1959), costing $2.5 million, an enormous financial and critical success and tied down a triumvirate of top talent in John Wayne, William Holden and John Ford for western The Horse Soldiers (1959), the actors pulling down $750,000 apiece.

Such salaries sent the nascent company on a collision course with traditional Hollywood. The majors “screamed” that independents were overpaying the talent, hefty profit shares accompanying the salaries.

On top of that in 1959 in the space of two weeks Mirisch spent a record $600,000 pre-publication on James Michener blockbuster Hawaii and tied up a deal to film Broadway hit West Side Story. Within two years of setting up, Walter Mirisch announced a $34.5 million production slate, earning the company the tag of “mini-major,” as part of a shift in attitude to a “go for broke” policy. By the start of the new decade it was by far the biggest independent the industry had ever seen, handling $50 million worth of product, including The Magnificent Seven and The Apartment (1960). Average budgets had risen from $1.5 million to $3.5 million.

To outsiders, assuming the Mirisch venture was Walter’s first, it might look as if Walter had knocked the ball out of the park in a very short space of time, but, in reality, by the time he produced Some Like it Hot, he had been responsible for thirty-three pictures. Not bad for a “beginner.”

Explained Walter Mirisch, “Producing films is a chancy business. To produce a really fine film requires the confluence of a large number of elements, all combined in the exactly correct proportions. It’s very difficult and that’s why it happens so infrequently. It takes great attention to detail, the right instincts, the right combinations of talents and the heavens deciding to smile down on the enterprise. Timing is often critical.”

What would have happened to Allied Artists, for example, had Wilder made Some Like it Hot there instead of Love in the Afternoon?

Added Walter, “Where is the country’s or the world’s interest at that time? What is the audience looking for? Asking them won’t help because they themselves will tell you they don’t know what they’re looking for. They don’t know what it is until they’ve seen it. All the elements must come together at exactly the right time. So to say one embarks with great certainty on such an endeavor is an exaggeration.”

After 33 films Mirisch hit a home run with Some Like It Hot and continued to do so throughout the 1960s chalking up further critical and commercials hits like The Pink Panther (1964), In the Heat of the Night (1967) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) and vacuuming up a stack of Oscars.

SOURCES: Walter Mirisch, I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History (University of Wisconsin, 2008); “Mirisch Freres Features Outlet Via United Artists,” Variety, August 7, 1957, p16; “3 Mirisch Bros Set Up Indie Co for 12 UA Films,” Variety, September 11, 1957, p7; “RKO vs Mirisch Kong,” Variety, September 11, 1957, p7; Advertisement, “United Artists Welcomes The Mirisch Company,” Variety, November, 13, 1957, p13; “Brynner, Mirisch Pledge UA TV Tie,” Variety, January 1, 1958, p23; “Mirisch Freres 6 By Year-End,” Variety, March 19, 1958, p3; “Majors Originated Outrageous Wages,” Variety, December 10, 1958, p4; “UA-Mirisch’s $600,000 For Michener’s Hawaii,” Variety, August 26, 1959, p5; “Mirisch West Side Story,” Variety, September 2, 1959, p4; “Mirisch Takes on ‘Major’ Mantle With 2-Yr $34,500,000 Production Slate,” Variety, October 21, 1959, 21; “Mirisch Sets $50,000,000 14-Pic Slate; Biggest for Single Indie,” Variety, August 17, 1960, p7.