Absolutely mesmeric. Would be catnip for contemporary audiences with its shifting time frames, juggling perspectives, narrative sleight-of-hand, and heavily feminist-oriented outlook with its slating of misogyny. Ripe for a remake and with the adventurous directors around these days they should be vying for the opportunity. But I should warn you, steer clear of the version that showed on Amazon Prime which cut the four-part television series in half.

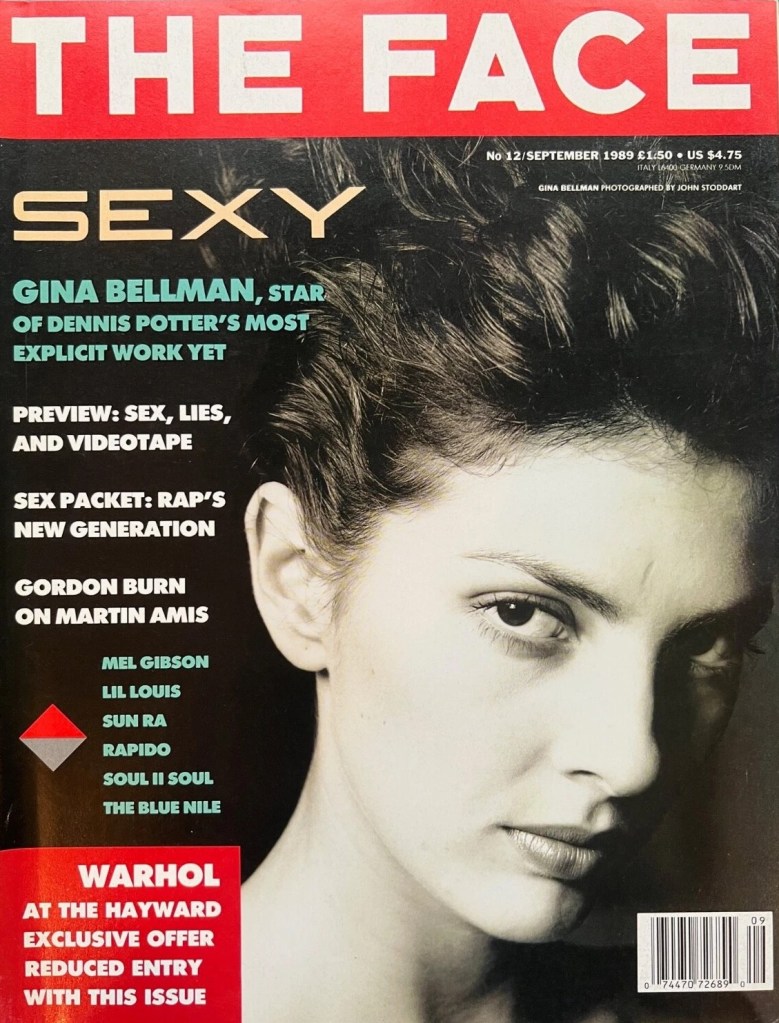

British screenwriter Dennis Potter was something of a national institution before this appeared, the BBC ponying up vast sums (in television terms) for his experimental programs that included the likes of Pennies from Heaven (1978) – remade as a movie three years later with Steve Martin – and The Singing Detective (1986) (remade seventeen years later with Robert Downey Jr) and his blend of pastiche and males struggling with raw emotion had made him not just a household name but accorded him worldwide acclaim.

However, just as Peeping Tom (1960) put the kibosh on the career of Michael Powell, Blackeyes proved a major critical reversal and after the mauling it received and outraged headlines in the national media Potter somewhat lost his mojo and automatic critical favor although Lipstick On Your Collar (1993) helped a certain Ewan McGregor to make his mark.

In part, Blackeyes is way ahead of its time in the use of the stylistic devices mentioned above which when incorporated into the works of, for example, David Lynch or Christopher Nolan, were hailed as groundbreaking.

So this is a three-hour-plus show setting precedents that not only break all the rules of narrative but blows them sky-high and has so many layers you can hardly keep up and that narrative spinning continues to the very end. You could almost entitle it “Whose Story Is It, Anyway?”

Elderly author Maurice (Michael Gough) has fashioned the experiences of his model niece Jessica (Carol Royle) into a bestselling literary novel. Leading character Blackeyes (Gina Bellman) is taken advantage of so often by men that she commits suicide, wading out dressed in sexy night attire into a lake. Although Maurice makes a fine specimen suited-and-booted and talking to admiring audiences at book fairs, in reality he’s a sodden old drunk living in a threadbare apartment with a teddy bear. But he’s intellectually adroit as shown with his verbal duels with a smug journalist who spouts artistic jargon.

Jessica is so annoyed that she has not been acknowledged as the source of her uncle’s novel – he claims it is a work of imagination – that she begins to write her own fictional version of her life story, calling into question some of the events in her uncle’s account. So that’s two perspectives already. Stand by for a third, that turns the entire story on its head.

It appears Blackeyes (Gina Bellman) has not committed suicide. Detective Blake (John Shrapnel) is convinced she has been murdered, especially after he finds a list of names stuck in her vagina (yes, despite Blake gamely searching for every euphemism under the sun, the actual word, to add to the shock and horror of an audience and especially critics reeling from the sex and nudity, was used on the BBC) and later finds her diary which provides another version of events.

He’s an old-school detective, and while not beating anyone up, not above handing out a good thump in the ribs to anyone giving him lip. So while following Maurice and his niece, we are also finding out more about Blackeyes via the cop’s investigations and how she was taken advantage of in the advertising profession and world of photographic modeling. She is even the one who gets the blame when someone tries to rape her.

Her life could be viewed in two ways, as a sexually independent woman or as a victim of MeToo.

To counteract what is presented as a sordid existence there comes into her life a gentler soul, advertising copywriter Jeff (Nigel Planer) and he’s writing and rewriting versions of a more old-fashioned romance where they enjoy a meet-cute (of sorts) and get talking and move onto romantic walks along the seaside. But Jeff’s too diffident a fellow to appeal to Blackeyes and he doesn’t even get to first base. But it also turns out that he’s been watching Jessica through binoculars (they live across the street from each other) and there’s a marvelous moment when he realizes that Blackeyes occupies the same apartment as Jessica and that he could at that very moment be watching himself.

All the way through there’s been a male voice-over, measured, commenting on the action, advising on twists in the story, adding a different perspective to characters, offering many polished bon mots, and it takes you quite a while to realize that this is an entirely new voice, and doesn’t belong to either Maurice or Jeff. In the ordinary run of things, this character would turn out to be the Hercule Poirot of the piece, putting the jigsaw together, explaining all.

In fact, he’s another element of the jigsaw. He’s not just the narrator. Everyone we’ve seen are characters in his fiction. But they don’t always obey the rules and at the very end Blackeyes escapes.

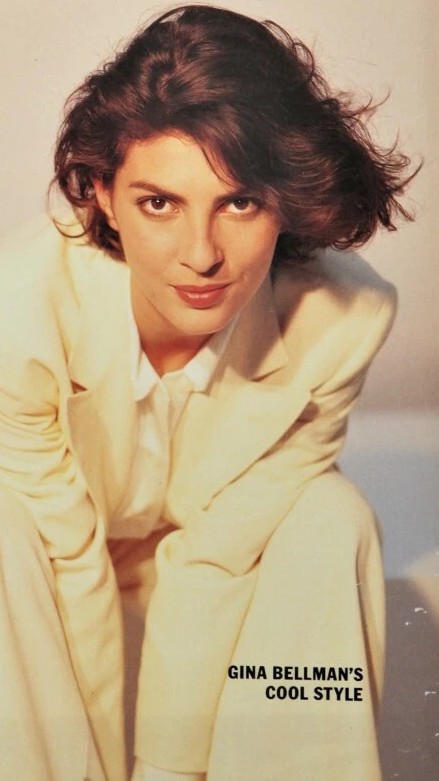

So just a stunning piece of television. Although Michael Gough (Batman Returns, 1992) received the bulk of what little plaudits there were, the series is carried by New Zealand actress Gina Bellman (Leverage, 2008-2012, and Leverage: Redemption, 2021-2023) who is simply superb. She rises above what could easily have been a cliché – and in some respects was written as a cliché version of the “dumb blonde” at male beck and call. Her comic timing for a start turns many scenes on their heads. But what’s often been overlooked is her transitional skill. She moves from male fantasy figure to believable human being and from there to rebel. And that takes some doing.

Gina Bellman hates talking about this series, my guess on account of the nudity and the backlash that created for a young actress, but she should be proud of her achievement. This is more than solid stuff.

Writer Dennis Potter also directed and his camera is always prowling around the edges.

The word auteur was over-used but this genuinely fits that category.

A masterpiece.