As much as the censor would permit – would be the subtitle. While not as harsh as the Nelson Algren source novel, it’s still, wrapped up in a bitter romance, a more brutal than heretofore expose of the sex worker, far removed from the gloss of Butterfield 8 (1960) or the romantic comedy of Never on Sunday (1960) and Irma La Douce (1963).

The initial thwarted romance lacks the tragic element. It falls apart due to the mundane. After a four-month affair Dove (Laurence Harvey) can’t commit to artist Hallie (Capucine) because his father is too ill to leave. So she ups sticks and heads for New York, hooks up with buyer Jo (Barbara Stanwyck) who turns out to invest in more than art, and ends up in a New Orleans brothel where as well as servicing the clients she can continue making sculptures.

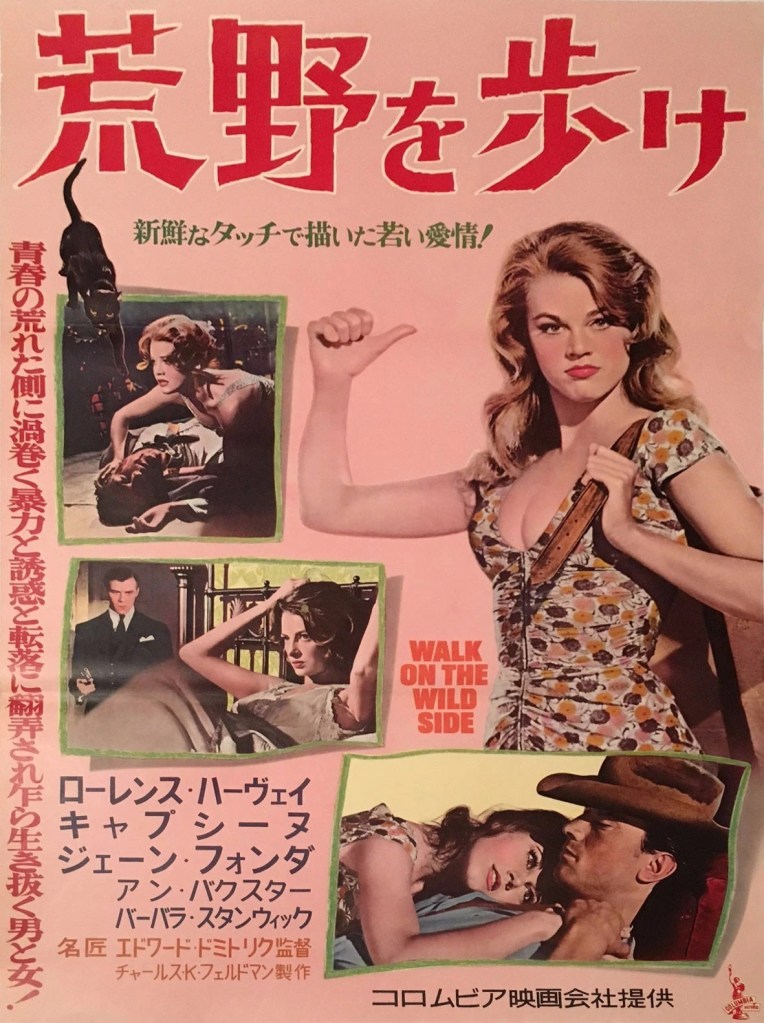

After his father dies three years later, Dove heads to New Orleans to find her, but with no idea where to look. He falls in with vagabond-cum-thief Kitty (Jane Fonda) and eventually having dumped her due to her thieving ways takes refuge in a café whose owner Teresina (Anne Baxter), a victim of Kitty, offers him employment. She suggests he puts an advert in a New Orleans newspaper and just when he’s giving up hope and Teresina is getting up her hopes that she can win him over romantically he gets a phone call.

He’s clearly unaware that Hallie is a sex worker and after romancing her sets them up in an apartment. Hallie abandons the reunion after a night or possibly just an idyllic afternoon. Hallie’s reluctance is twofold. She’s become accustomed to the relative laziness of her life, she’s a high-class lady and is not worked too hard, plus she’s got accommodation and a studio to work in and she knows her boss Jo is sweet on her. On the other hand, it would be difficult to quit, the brothel employs tough guy Oliver to keep the girls in line and nobody’s going to want her to be giving it away for free.

Kitty, now working in the establishment, annoyed that he previously rejected her advances, gives Dove a full run-down on his lover. And there’s a legal catch that Jo is quick to take advantage of. Since Kitty is now a sex worker and it was Dove who took her with him to New Orleans he could be prosecuted for sex trafficking of a minor. When that doesn’t work, Dove receives a beating.

Kitty now decides Dove isn’t so bad after all, feels remorse at her role in his downfall, and helps him get back to café where Teresina cares for him and gets her hopes up once again. Then she helps Hallie escape and then fesses up to Oliver where she is. It doesn’t end well – although the censor would be pleased since after the climactic fracas the brothel is closed down and Jo and Co jailed.

It’s got a Tennessee Williams feel, though everything set in the South appeared to come into his bailiwick, but most of the realism is understated, as it would have to be in those times. Jo’s a groomer of the vulnerable, and for all Hallie’s artistic ambition she’s every bit as easy pickings as Kitty who is grateful to be freed from prison where she was arrested as a vagrant and reckons being given money for fancy clothes and having a roof over her head is good enough reward for selling body and soul. Her role in the denouement is a mite too convenient from the narrative perspective but it will do as a means of tacking on a tragic ending.

It helps enormously that most of the performances are understated. Laurence Harvey (A Dandy in Aspic, 1967), more commonly a scene-stealer, is good value and Barbara Stanwyck (The Night Walker, 1964) only requires a stare to make her feelings known. Though Capucine (Song without End, 1960) was criticized at the time I felt her performance was measured. Jane Fonda (Barbarella, 1968) was more of a wild card and it didn’t seem believable that such a flighty piece was going to become principled.

You can thank director Edward Dymytryk (Shalako, 1968) for keeping the actors in line and maintaining an even tone without spilling over into the melodramatic. John Fante (My Six Loves, 1963) and Edmund Morris (The Savage Guns, 1961) adapted the book. Special nod of appreciation to Saul Bass for the credits.