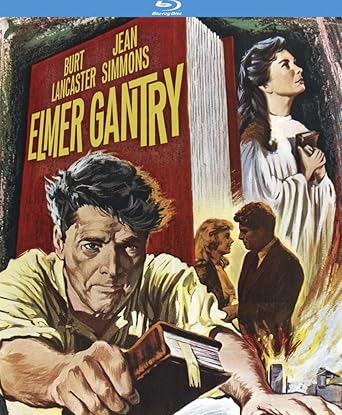

Burt Lancaster gives the performance of his life as the eponymous burnt-out salesman finding financial redemption in the salvation business in Richard Brooks’ riveting examination of the revivalist boom. While replete with hypocrisy, old-style religion brought succour to the rural poor, but the director takes such an even-handed approach to the subject matter, carefully nurturing a marvellous parade of characters, that you are totally sucked in.

Brooks made his name adapting famous novels but only here and In Cold Blood (1967) does he exhibit complete mastery of the material. In fact, he pulls out a cinematic plum in having the audience, who might initially have mocked the obvious manipulation of the poor, suddenly taking the side of the itinerant preachers when they come up against the more sophisticated religious operators in the big towns.

Elmer Gantry (Burt Lancaster) has some previous in the preaching business, but only for as long as it took for him to be chucked out of divinity school for seducing the principal’s daughter, so when by accident he comes upon a touring revivalist meeting he discovers his metier as a fast-talking brazen preacher. He doesn’t quite usurp the star of the show, Sister Sharon (Jean Simmons), and in fact their styles complement one another, he preaching hell and damnation, she the love of God.

Beneath the demure guise, Sharon is anything but a push-over. Not only does she see through him right away and consistently knock him back but she is quite the businessperson, though her methods of keeping civic officials in line often rely on blackmail. But then who are the hypocritical, allowing speakeasies and prostitution to run rampant, to attempt to rein in revivalists who need account to no one for how they spend their revenue?

Eventually, of course, Elmer’s ardent wooing wins over the virgin Sharon who easily forgives his dalliance with her doe-eyed follower Sister Rachel (Patti Paige). Burgeoning romance is scuppered by a chance encounter with prostitute Lulu (Shirley Jones), the principal’s daughter. That’s just the spark needed for anti-religious fervor to take over and the enterprise ends in disaster.

But what’s so good about a film that could as easily just relied on taking pot-shots at religion is that Brooks gives equal space to the good and bad in each character. Sure, Elmer’s confession of his sins might be construed as a seduction device, but that’s tempered by a genuine ruefulness and remorse over his previous actions. And while his grand-standing in front of an audience could be interpreted as merely an actor revelling in a role, you can see that religion has as easily taken over him and provided him with an identity that he finds rewarding. He might still be a salesman but he’s selling the hell out of the product.

Sharon’s uncanny hold over a congregation may be a true skill, and she’s definitely a believer, but that is borne out of fiction. She has reinvented herself, given herself a new name and identity, that furnished her with business opportunity in a male-dominated world, but love of God has come at the expense of love of man.

Perhaps what’s best about the picture’s construction is the array of supporting characters. Journalist Jim (Arthur Kennedy) might appear the pick, ingratiating himself with the touring company only to write a searing expose, but drawing the line, and incurring the wrath of his editor, at writing the kind of tawdry tale he believes is a fabrication. While still holding a torch for Elmer, Lulu has none of the cliché prostitute’s heart of gold. Initially rejected by Elmer, she goes along with a scheme to bring him down, only to change her mind and change it again, left only with remorse.

And Brooks manages to weave in a ton of detail, sometimes in dramatic fashion, such as the church elders in big city Zenith debating the value of backing the revivalists (the touring operation usually signs up hundreds of people to local parishes), and sometimes just as background, such as when Jim dictates his front-page lead in the newspaper office, whipping it off a page at a time to throw in front of the editor.

There’s also a little-commented-upon affinity between Shirley and Elmer. She, too, is coming to the end of the line. She is approaching burn-out. The endless travel, the responsibility for her payroll, financing accommodation, dealing with officials, seeing all the people she has returned to the fold being handed over to local churches, is taking its toll. And she wants the stability of her own church, where she can soothe her congregation on a weekly basis and live a more temperate life.

If ever a movie suited Burt Lancaster’s physicality, this is it. Allowed to channel his inner dominance, every gesture overpowers and by the same token makes him more potent when at his most abject. Lancaster (The Swimmer, 1968) was in a rich vein of form that would see him deliver a series of majestic performances throughout the decade. He deservedly won the Oscar.

Jean Simmons (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) is, effectively, both a villain, duping everyone by her creation of Sister Sharon, and the epitome of the American Dream, a girl from shantytown who makes her way bigtime. Shirley Jones (Two Rode Together, 1961) is afforded more dramatic beats and hers is a sure-footed performance, leading you to believe she will react one way and then go another. Oddly, Arthur Kennedy (Joy in the Morning, 1965) missed out on adding to his five Oscar nominations for supporting actor.

Nothing in this movie has aged. If anything, this was way ahead of its time in daring to pick holes in organized religion (The Cardinal and The Shoes of the Fisherman were a good few years away and in The Night of the Hunter a few years before Robert Mitchum only posed as a preacher).

Extraordinary movie by Richard Brooks at the top of his form.