A dislocated, fractured film about disjointed, fractured people. Takes a heck of a long time to work what’s going on because director Richard Lester in the elliptical style of the times tells us bits of the story a bit at a time and no guarantee anything is in logical order or that the characters tell the truth about themselves or their actions. And, unusually, outside of a western, all the men appear prone to violence.

Petulia (Julie Christie), a self-appointed “kookie” (in the vernacular of the times) and married for just six months to wealthy naval architect David (Richard Chamberlain), for no reason at all begins an affair with surgeon Archie (George C. Scott) that she encounters at a posh function. Archie, getting divorced for no reason at all except boredom from Polo (Shirley Knight), already has a girlfriend, all-round-sensible boutique-owner May (Pippa Scott). Petulia and Archie may or may not have consummated the affair, she certainly puts him off often enough. Petulia may or may not be the daughter and sister of prostitutes. You see where this is going? Unreliable narrator, par excellence.

A broken rib may be the result of stealing a tuba from a shop. She could have cracked her head open after a dizzy spell. A Mexican boy keeps turning up and, it has to be said, nuns. It’s all very avant-garde: an automated hotel where the key comes out of slot and the fob sets off flashing lights at the bedroom door, the televisions in hospital rooms are dummies, Janis Joplin is the singer in a band, characters viewed in longshot down corridors, up car park ramps, emerging from tunnels.

Eventually the demented jigsaw puzzle comes together but not after a tsunami of overlapping dialog, flash scenes and snippets that have nothing to do with the film. It’s San Francisco so there’s a scene in Alcatraz. But little is constant, every marriage seems on the verge of break-up, even the contented Wilma (Kathleen Weddoes), wife of another surgeon, wishes she had Archie’s courage in ending his marriage.

But Petulia is anything but free-spirited. She is trapped and doesn’t know how to get what she wants. She may be a tad unconventional and big-hearted and occasionally small-minded but once you get to the end of the film and find what she really wants the rest of her behavior makes sense. And although Archie is able to verbalize what he doesn’t want from marriage, the only option open to Petulia is one apparently mad action after another.

Although set in the Swinging Sixties, the male hierarchical system remains dominant. Archie’s ex-wife relies on him for money, David and his father (Joseph Cotten) hold sway over Petulia regardless of her bids for freedom. David is unsavory, his father is willing to provide a false alibi, another surgeon Barney (Arthur Hill) lets loose with a vicious rant and even the harmless soft spoken Archie lets loose on Polo.

Julie Christie (Doctor Zhivago, 1965) makes Petulia as irritating as she is endearing, the freedom she expects to embrace in the counterculture impossible to grasp, leaving her only with the vulnerability of the vanquished. George C. Scott (The Hustler, 1961) has forsaken his growling persona, the volcanic screen presence set to one side, to portray a more interesting character, bemused by Petulia but ultimately standing up for her.

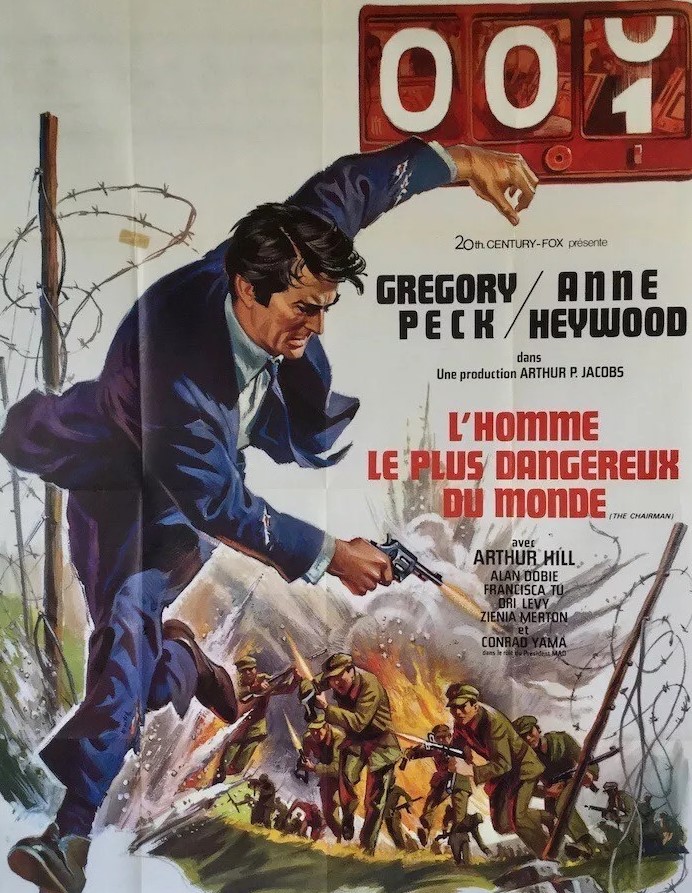

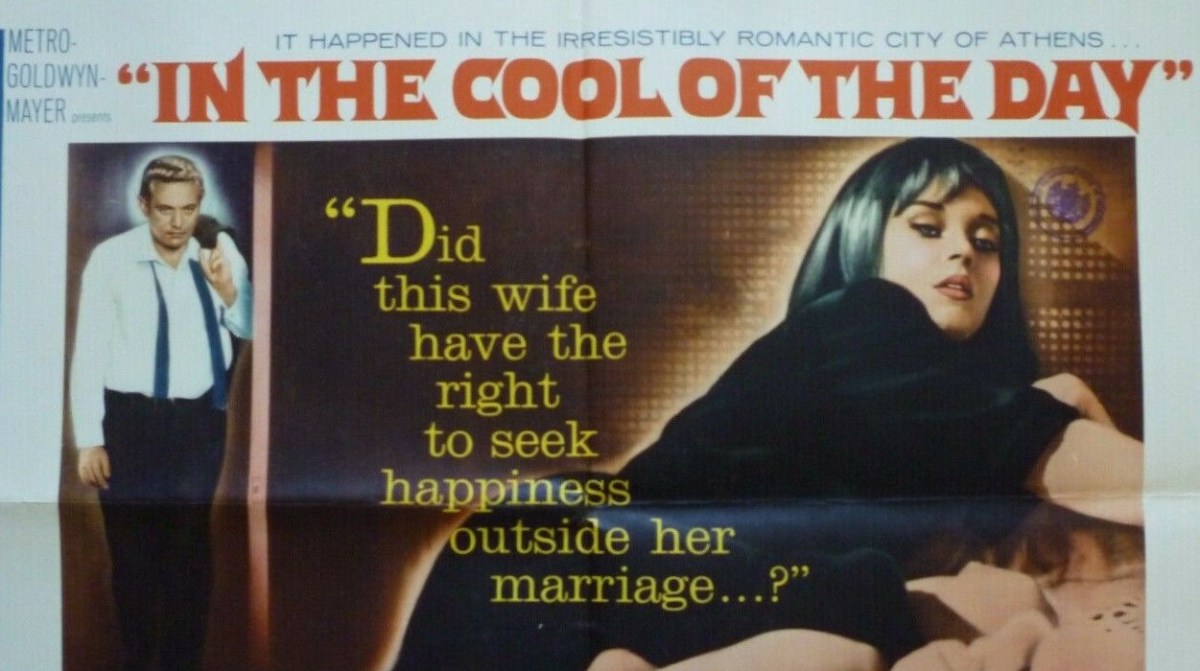

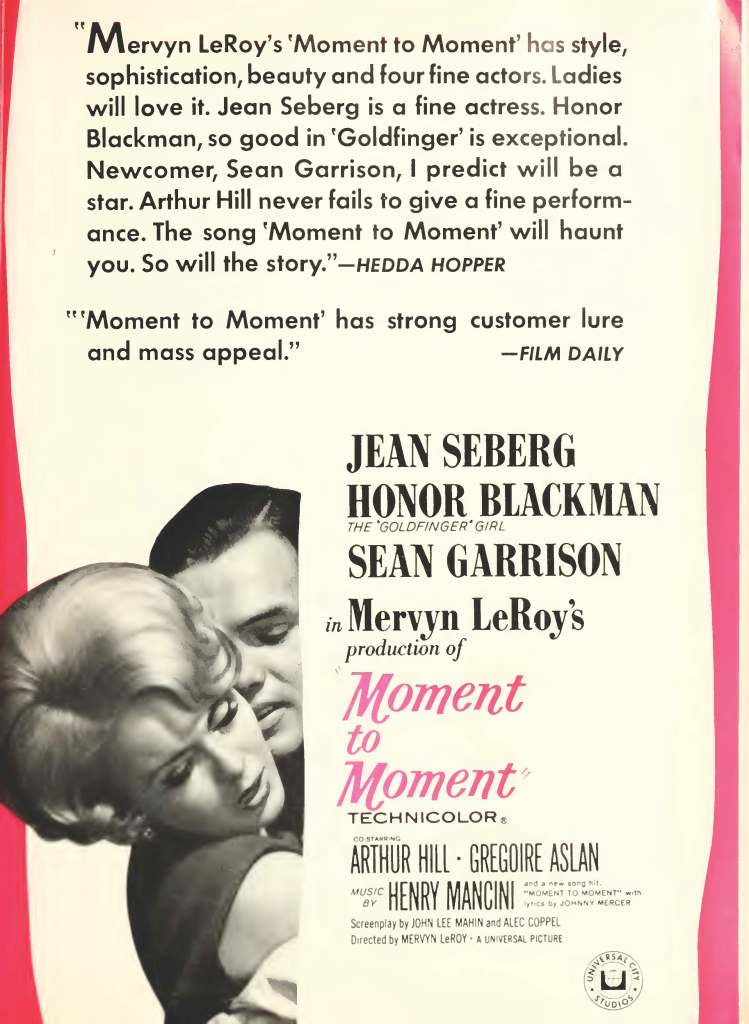

There’s an excellent supporting cast in Richard Chamberlain, still in the process of shucking off Dr Kildare (1961-1966), Arthur Hill (Moment to Moment, 1966), Shirley Knight (Flight from Ashiya, 1964) and Joseph Cotten (The Third Man, 1949).

Britisher Richard Lester (A Hard Day’s Night) was a director du jour who, while fulfilling the expectation of delivering cutting-edge techniques and casting a wry eye on contemporary mores, offered some surprisingly more homely family scenes and for a movie which is so much about the distance between characters many scenes of just touching, Petulia stroking Archie’s hands, Archie stroking is wife’s neck, even when the intimacy they seek is a forlorn hope. The incident with the tuba which would be a meet-cute to end all meet-cutes in other pictures turns into a cumbersome irrelevance. You get the impression that the chopping up of the time frames and the points of view reflects the characters’ feelings that they can impose their own reality on a situation. Lawrence B. Marcus (Justine, 1969) wrote the screenplay from the novel Me and the Arch Kook Petulia by John Hasse.

Check out a Behind the Scenes on this film’s Pressbook.