The sci-fi elements in this tidy paranoia thriller set in Communist China are not the only issues overlooked at the time and worthy of reconsideration now. Anyone who blasted it for supposedly political jingoism conspicuously failed to read a subtext that chimed with young left-wingers for whom Chairman Mao was not, as now, perceived as a tyrant du jour but as a political god. There’s a distinct whiff of Philip K. Dick in the implanting in a spy’s head of not just a tracking/listening device but one laced with explosive that can be remotely triggered for suicidal or murderous gain. Needless to say, the spy, ignorant of this fact, was a de facto sacrificial lamb. And a key plot thread about genetically modified crops as a means of solving world hunger came about four decades too early.

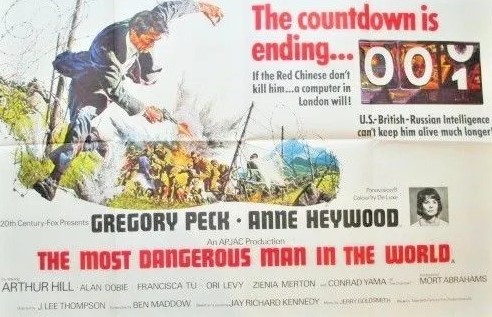

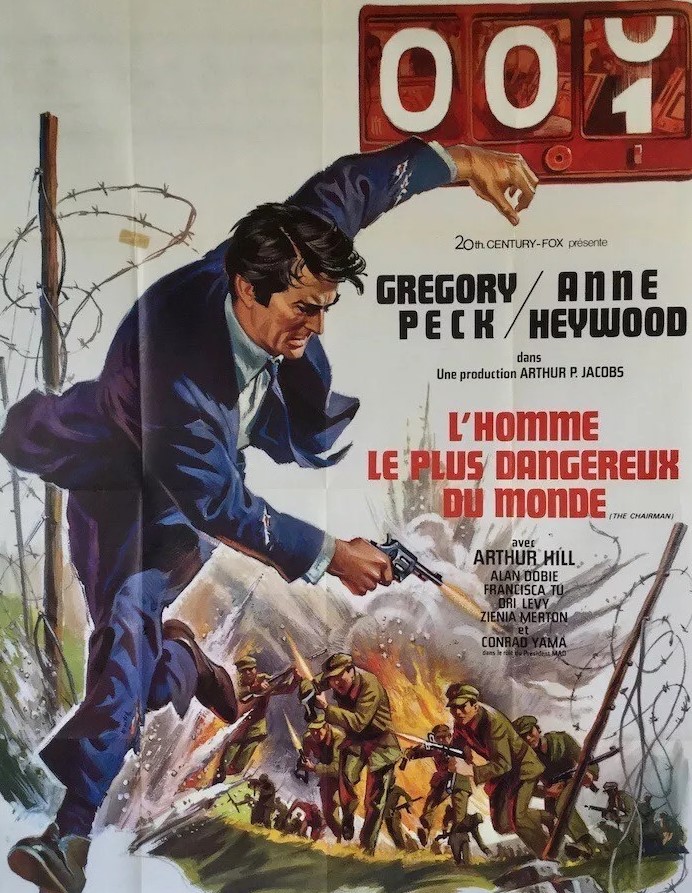

Widowed Nobel prize winning scientist Dr Hathaway (Gregory Peck) is despatched into China via Hong Kong to contact a missing scientist with a revolutionary formula for an enzyme. A series of crisp flashbacks set up the scenario of the tracking device and a reverse echo of Marooned (1969) where Army chiefs back at base, led by one-eyed Shelby (Arthur Hill,) can listen in but are helpless to intervene – except in sinister manner. Shelby considers Hathaway “the wrong brilliant man” for the task and that they have sent in “a civilian to do a soldier’s job.”

The hidden transmitter allows Hathaway to keep his superiors posted but the listening device also picks up a creaking bed as Hathaway almost falls into a honey trap in Hong Kong. Amazingly, he doesn’t have to sneak into China but is welcomed with open arms and hustled along to a meeting, and a game of ping-pong (the real thing and the verbal equivalent) with Chairman Mao (Conrad Yama). While spouting some propaganda, Mao is surprisingly open about sharing the secret of the enzyme rather than blackmailing a starving world. Meanwhile, it’s the Americans who are more interested in the double cross, Shelby itching to blow up Hathaway’s head in the assumption the explosion would dispose of the Chinese leader.

Emissions from the transmitter are tangling up the airwaves, making the Chinese secret police highly suspicious of Hathaway as he heads for the secret scientific compound housing Professor Soong Li (Keye Luke), creator of the enzyme, and his daughter Chu (Francesca Tu).

Turns out Hathaway has been summoned by the professor to help find a missing link in molecular chains. Hathaway has to burgle his way to steal the formula, but fails to find it, but when the professor commits suicide and is denounced by his daughter and the Chinese secret police close in, Hathaway has to scarper and head for the Russian border, that country, oddly enough for a spy movie, being on the same side as the Yanks. Meanwhile, Shelby’s trigger finger it itching to blow his man sky high for fear he might give away details of his mission.

Turns on its head many of the spy film’s truisms: firstly that Hathaway effectively fails in his mission; secondly that patriotism doesn’t blind him to his country’s greed or folly; thirdly that’s he not in constant seduction mode.

Political argument that one point seemed to excessively delay the narrative thrust, now, at half a century’s move, seems more considered and providing an interesting balance between opposing views.

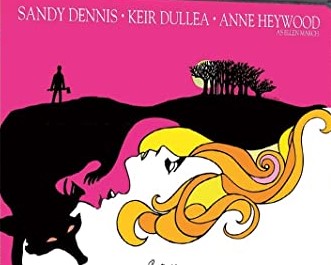

Gregory Peck (Marooned, 1969) is at his quizzical best, deeply-rooted scepticism helping to anchor his character. But if you were attracted by seeing Anne Heywood (The Fox, 1967) second-billed you’re in for a disappointment as she just tops and tails the picture. Arthur Hill (Moment to Moment, 1966) is good value as always.

But it’s testament to J. Lee Thompson (Mackenna’s Gold, 1969, also starring Peck) that his direction brings together diverse political/sci fi/spy/thriller elements in a winning formula, ignoring the obvious. Some interesting detail: someone handing out coffee on a tray to the inmates of the command station; Hathaway’s guilt at his role in the death of his wife barely touched upon, but it explains a lot; Mao’s famous Little Red Book provides a twist.

Occasional flaw: surely the Chinese would have bugged Hathaway’s room and catching him, however soft voiced, filling in his superiors. The idea that the Chinese could be technologically more advanced than the U.S. would have had John Sturges in a fit of fury, but Thompson takes it in his stride. Screenplay by Ben Maddow (The Way West, 1967) and Jay Richard Kennedy (I’ll Cry Tomorrow, 1955).

Reassessment overdue.