Low budget sci-fi effort that had little chance in the box office stakes that year up against the big budget psychedelic 2001: A Space Odyssey and the visceral Planet of the Apes. Producer George Pal and director Byron Haskin, the key figures behind War of the Worlds (1953), would later become among the most exalted in the sci-fi genre, but the cult of the 1950s sci-fi movies did not exist yet. Yet if made today, we would be treating this as an origin story with a sequel already in the works and creation of its own universe on the cards.

As the budget can only accommodate a few explosions and a derisory number of tiny special effects, emphasis is placed on imagination as the source of tension. The uncanny remaining unexplained helps ensure mystery remains character-driven. Wisely, the film makers steer clear of providing any detail on the strange force.

It begins with the neat title “Tomorrow.” As part of a planned space program, a team of scientists experimenting on the limits of human endurance discover that one of them has unusual powers. As a group they are able to make revolve a piece of paper attached to a vertical pencil without establishing who is the driving force. When Professor Hallson (Arthur O’Connell) is found dead in a centrifuge, the only clue being a scrap of paper bearing the name Adam Hart, suspicion falls on the other members. Professor Tanner (George Hamilton) is dismissed when the investigation discovers his credentials are fraudulent.

Seeking to prove his innocence, Tanner goes on the run before establishing that the main suspects are the mysterious Adam Hart and three of the original team – military chief Nordlund (Michael Rennie), Professor Scott (Earl Holliman) and Tanner’s girlfriend Professor Lansing (Suzanne Pleshette). But he is mostly baffled by the goings-on which include being dumped in an air force target range. He could be the culprit but again so many odd occurrences take place when others are present that it would be hard to pin the blame on Tanner. As the corpses begin to pile up, the list of potential suspects naturally decreases.

A toy winks at Tanner, walls appear were there were none before, a man is convinced Tanner is someone else (not Hart), a high-flying professor’s wife lives in a trailer, characters collapse under psychic assault, a young woman trying to seduce an old man discovers she is kissing a corpse, the imagery appears inspired by Salvador Dali and Hieronymus Bosch, and you could easily argue that Tanner’s academic records have been deliberately erased. On the more prosaic side, the cops are next to useless, there’s a car chase and a sequence in a lift shaft, but the bulging eyeballs suggested in the posters are a marketeer’s invention. There’s even a clever joke, Tanner misreading a newspaper headline “Don’t Run” as being a message to him.

The oddities are sufficiently off-beam to appear as figments of the imagination and it certainly seems Tanner suffers from hallucinations. And there are some deliciously off-key characters, an old woman obsessed with fly-swatting, a sultry waitress. If Hart is the superhuman then experiments may have taken place long before now. In his hometown, people still act on instructions Hart handed out a decade before and accomplices are in place such as Professor Van Zandt (Richard Carlson).

Adding to the mood are philosophic discussions about the existence (as already a fait accompli) of a superhuman: some want to clone him, others would happily submit to him.

Byron Haskin (Conquest of Space, 1955) and George Pal ( The Time Machine, 1960) have marshalled their puny resources with exceptional skill, down to hiring as leading man George Hamilton (Your Cheatin’ Heart, 1964), so far from being a big star at the time that audiences would not automatically assume he had to be the good guy, and peopling the production with names from 1950s sci-fi like Michael Rennie (The Day the Earth Stood Still, 1951) and Richard Carlson (Creature from the Black Lagoon, 1954).

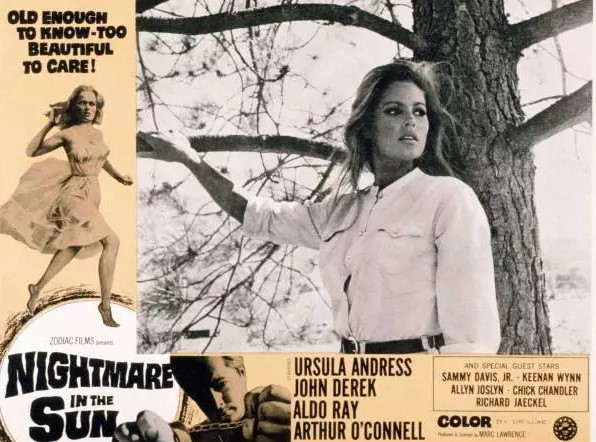

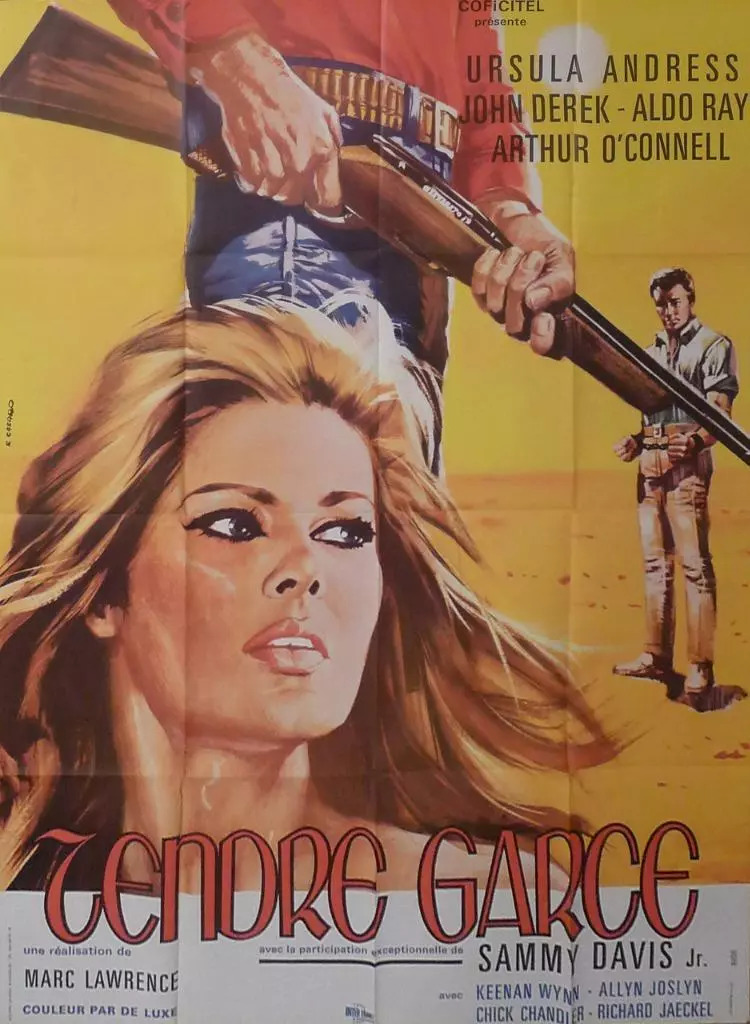

George Hamilton, in the days before the perma-tan became his calling card, is surprisingly good and the supporting cast does what a good supporting cast should do. Suzanne Pleshette (Nevada Smith, 1966) convinces as the lover who could be the cool killer. Also look out for 1940s glamor puss Yvonne De Carlo and a staple of The Munsters television series (1964-1966), Aldo Ray (Johnny Nobody, 1960) and Miko Taka (Walk, Don’t Run, 1966).

Perhaps the biggest coup was the recruitment of triple Oscar-winner Miklos Rosza (Ben-Hur, 1959) who provided a memorable score.

In most sci-fi films, the danger is readily identified. Here, you might hazard a guess but whenever you come close some clever sleight-of-hand misdirects. For most of the time I was happily intrigued, enough coming out of left field to provide distraction. This is a masterclass in how extract the most from very little.