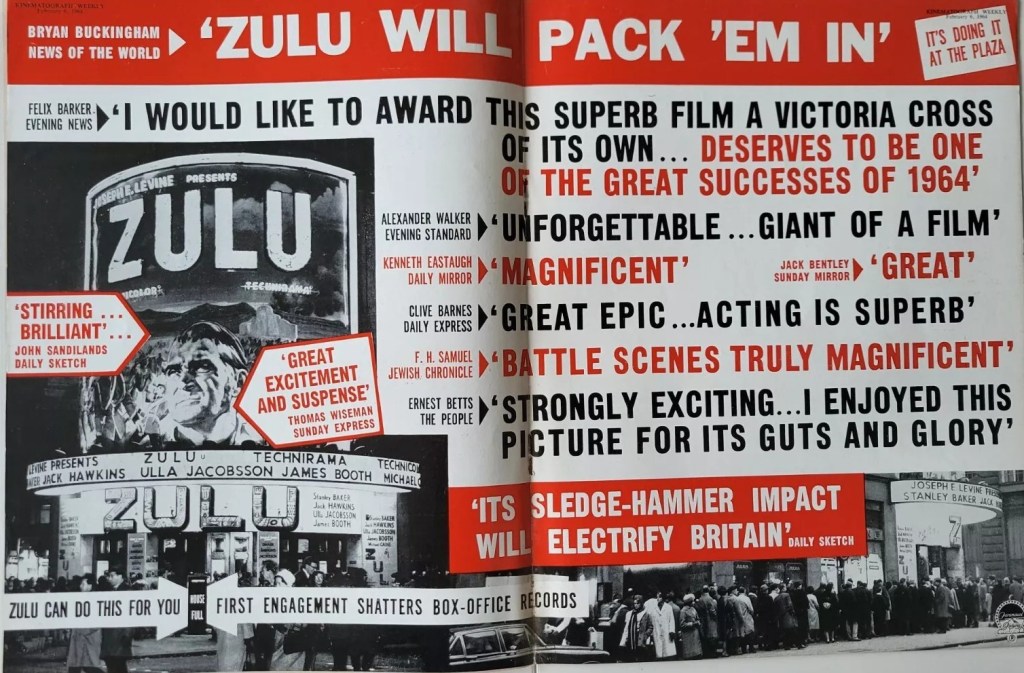

The technical excellence is substantially under-rated. Not just the aural qualities – the approaching enemy sounding like a train – and the reverse camera and uplifted faces registering awe that later became synonymous with Steven Spielberg, but the greatest use of the tracking camera in the history of the cinema. So what could otherwise be a rather static movie given it revolves around a siege is provided with almost continuous fluidity.

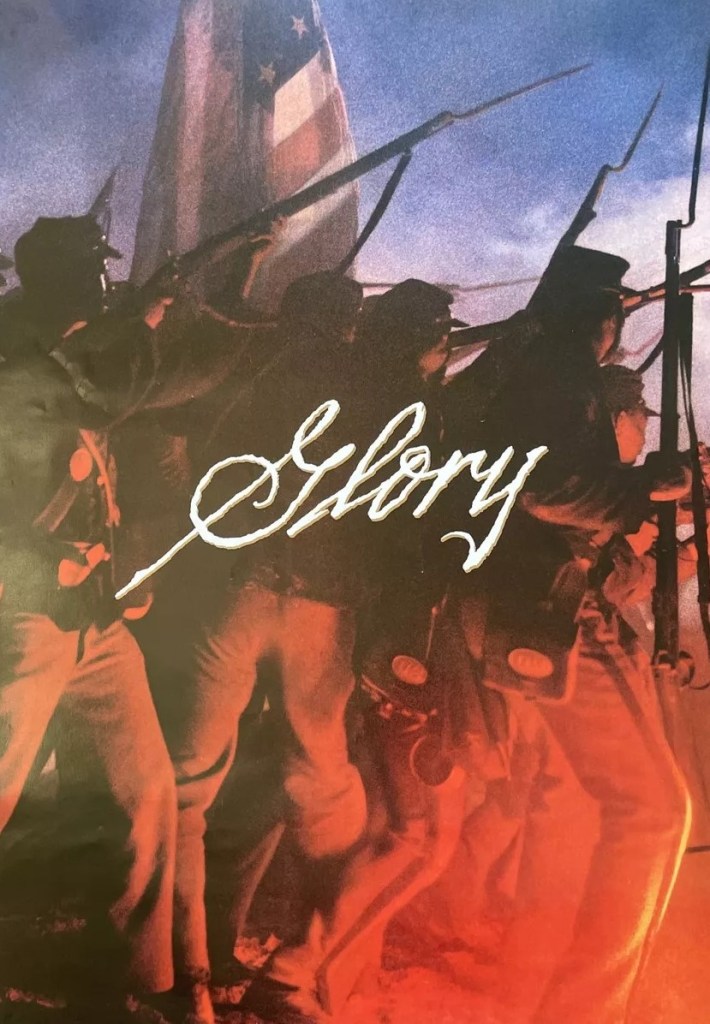

It’s perhaps worth pointing out, in relation to accusations of jingoism, that the British had relatively few battles to celebrate – Agincourt in the Middle Ages, Waterloo in 1815, El Alamein in 1942. But the Crimean War, in which Britain was on the winning side, was remembered for the disastrous Charge of the Light Brigade. Dunkirk in 1940 was a defeat and in cinematic terms D-Day was seen as heavily favoring of the Americans. Although there had been a corps of British World War Two pictures, these generally focused on individual missions (The Dam Busters, 1955) or characters (Reach for the Sky, 1956). And in fact the defense of Rorke’s Drift was preceded by a resounding defeat at the hands of the Zulus at Isandlwana.

Tactically, too, the Zulus are smarter. Their leader is only too happy to sacrifice dozens of his troops in order to gauge the British firepower, their snipers probe for weaknesses in the British defences, their troops feint to attract fire and waste bullets. The Zulus are too clever to attack where the British want.

This is not even your normal British army. Rorke’s Drift is a supply station and hospital. Its upper class commander Lt Bromhead (Michael Chard) idles his time away going big game hunting. The more down-to-earth Lt Chard (Stanley Baker) is there in his capacity as an engineer, erecting a pontoon bridge over the river. Neither has been in battle.

It’s surprisingly realistic in its depiction of the common soldier as having other interests beyond fighting. Private Owen (Ivor Emmanuel) is more concerned about the company choir, Byrne (Kerry Jordan) more focused on his cooking than bearing arms, and farmer Private Thomas (Neil McCarthy) spends his time cuddling a calf. Hook (James Booth) is a troublemaker and slacker and surgeon Reynolds (Patrick Magee) inclined to mouth off to his superior officers. The Rev Witt (Jack Hawkins) turns out to be a drunken hypocrite. His pious daughter (Ulla Jacobsen) is shocked when the men try to steal a kiss

Beyond a fleeting glimpse of victorious forces at Isandlwana, the Zulus are introduced in a sequence of harmony, a tribal ritual preceding a marriage ceremony, lusty singing and dancing scarcely setting up what is to come. It’s more like the by-now traditional section where the main characters in a movie set in an exotic land are introduced to aspects of local culture. Various characters attest to their military exploits.

But after that, tension cleverly builds. Witt raises the alarm, a bunch of cavalry irregulars refuse to stay and fight, the sound of the pounding “train” of the approaching army (an idea imitated for the oncoming unseen German tanks in Battle of the Bulge, 1965) and then the awesome shot of the thousands of Zulus adorning a hilltop make it unlikely the garrison can survive, especially given the inexperience of Chard and Bromhead, the latter of the civil “old boy” old school, and their inherent rivalry. Nor are the commanders typical. Chard may be gruff but he’s not arrogant and the soft-spoken Bromhead is the antithesis of every British officer you’ve ever seen on screen.

As the camera continues its insistent prowl, many sequences stand out – the battle of the battle hymns (“Men of Harlech” from the Brits); the bandage unravelling from the leg of wounded Swiss; the blackened wisps of canvas on the burning wagons at Isandlwana; the trembling voice of Color Sgt Bourne (Nigel Green) in the post-battle roll call; “he’s a dead paperhanger now”; the frantic bayonets digging holes in the walls of the hospital to escape; the final “salute” by the defeated Zulus; the torrential firepower the defenders inflict when three units fire in turn.

There’s a scene you’ll remember from The Godfather (1972) when Michael Corleone and the baker’s son stand guard outside the hospital and the baker’s hand shakes when he tries to light a cigarette whereas Michael notes that his own is perfectly steady. That has its precedent here. Chard’s hand shakes loading bullets into his pistol but later, battle-hardened, it does not.

There’s no glory in war as the surgeon constantly reminds the leaders and Bromhead, expecting to exult in triumph, instead feels “sick and ashamed.”

Terrific performances all round, mighty score by John Barry, written by director Cy Endfield (Sands of the Kalahari, 1965) and Scottish historian John Prebble (Culloden, 1964). The high point of Endfield’s career. Despite his character’s prominence Michael Caine was low down the billing, and despite the movie’s success stardom did not immediately beckon and he had to wait until The Ipcress File (1965) and Alfie (1966) for that.

I hadn’t see this in a long while and expected to come at it in more picky fashion. Instead, I thought it was just terrific.