You might be surprised to learn that many of the “Behind the Scenes” articles that feature in the Blog have become more popular than some of the reviews. As regular readers will know I am fascinated by problems incurred in making movies. Most of the material has come from my own digging, and sources are always quoted at the end of each article. Alistair MacLean still exerts fascination – three films in the Top Ten. Last year’s positions in brackets.

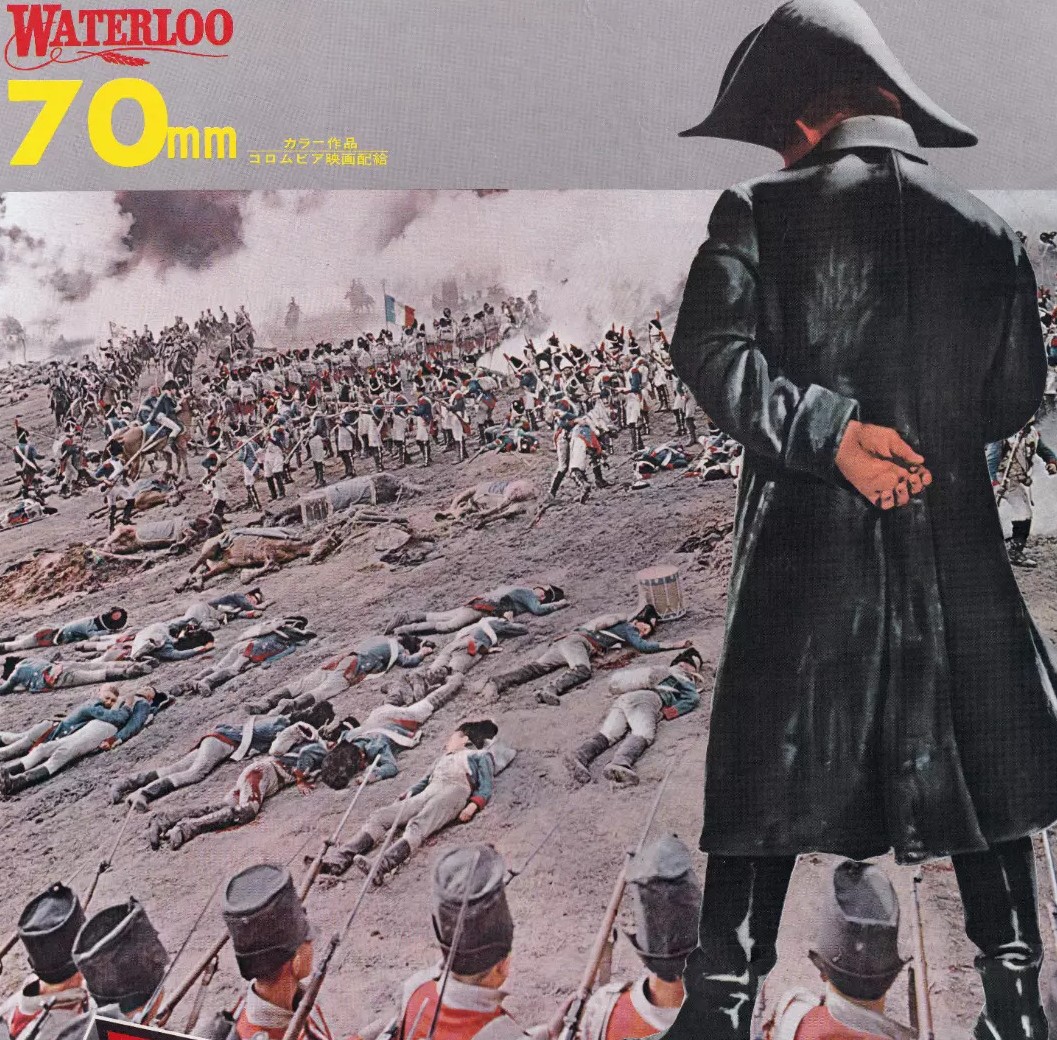

- (1) Waterloo (1970). No doubting the effect of Ridley Scott’s Napoleon in increasing interest in this famous flop that had Rod Steiger’s French emperor squaring off against Christopher Plummer.

- (9) Man’s Favorite Sport (1964). Howard Hawks back in the gender wars with Rock Hudson being taken down a peg by Paula Prentiss.

- (3) In Harm’s Way (1965). Otto Preminger takes off the gloves to expose problems in the American military around Pearl Harbor.

- (7) The Guns of Navarone (1961). The ultimate template for the men-on-a-mission war picture with an all-star cast and enough jeopardy to qualify for a movie of its own.

- (2) Ice Station Zebra (1968). A complete cast overhaul and ground-breaking special effects are at the core of this filming of another Alistair MacLean tale.

- (4) Battle of the Bulge (1965). There were going to be two versions, so the race was on to get this one to the public first.

- (6) The Satan Bug (1965). The problems facing director John Sturges in adapting the Alistair MacLean pandemic classic for the big screen.

- (5) Cast a Giant Shadow (1965). Producer Melville Shavelson wrote a book about his experiences and this and other material relating the arduous task of bringing the Kirk Douglas-starrer to the screen are told here.

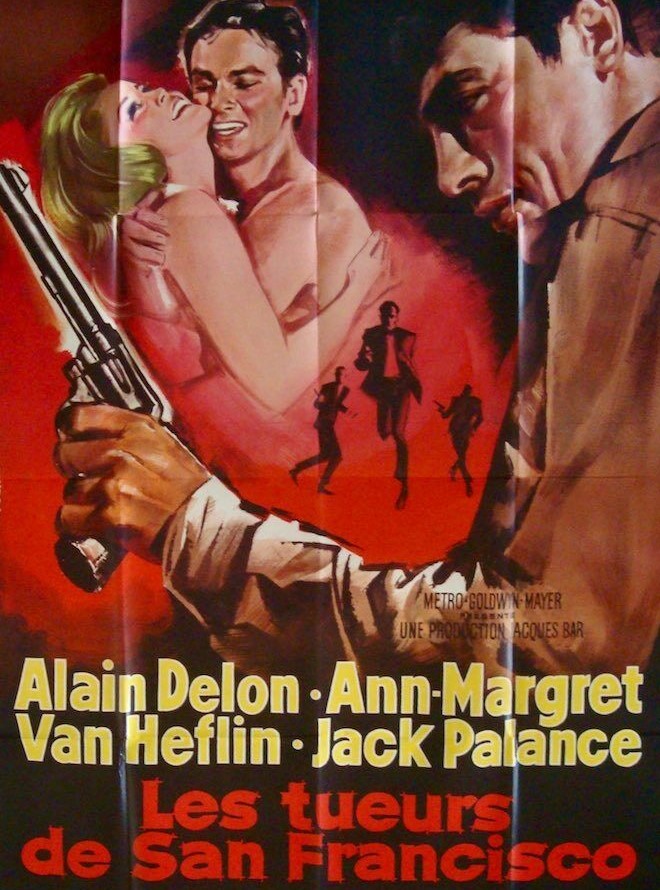

- (10) The Girl on a Motorcycle / Naked under Leather (1968). Cult classic starring Marianne Faithful and Alain Delon had a rocky road to release, especially in the U.S. where the censor was not happy.

- (New Entry) The Sons of Katie Elder (1965). First envisioned nearly a decade before, Henry Hathaway western finally hit the screen with John Wayne and Dean Martin.

- (11). Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). Richard Fleischer dispenses with the all-star cast in favor of even-handed verisimilitude.

- (New entry) Mackenna’s Gold (1969). Tortuous route to the screen for Carl Foreman-produced roadshow western, filmed in 70mm Cinerama, with an all-star cast including Omar Sharif, Gregory Peck and Telly Savalas.

- (8) Sink the Bismarck! (1960). Documentary-style British World War Two classic with Kenneth More exhibiting the stiffest of stiff-upper-lips.

- (13). The Bridge at Remagen (1969). British director John Guillerman hits trouble filming World War Two picture starring George Segal and Robert Vaughn.

- (New entry) The Trouble with Angels (1966). Less than angelic Hayley Mills sparring with convent boss Rosalind Russell. Directed by one-time star Ida Lupino.

- (New entry) For a Few Dollars More (1965). Sergio Leone sequel to first spaghetti western brings in Lee van Cleef to pair with Clint Eastwood.

- (New entry) How The West Was Won (1962). First non-travelog Cinerama picture, all-star cast and all-star team of directors tackling multi-generational western and all sorts of logistical problems.

- (New entry) Bandolero! (1968). Director Andrew V. McLaglen teams up with James Stewart, Dean Martin and Raquel Welch to fight Mexican bandits.

- (New Entry) The Train (1964). John Frankenheimer replaced Arthur Penn in the directorial chair to steer home unusual over-budget World War Two picture with Burt Lancaster trying to steal art treasures from under the nose of German Paul Schofield.

- (17) The Collector (1963). William Wyler’s creepy adaptation of John Fowles’ creepy bestseller with Terence Stamp and Samatha Eggar.