It wasn’t just the censor who put paid to the chances of some films receiving a cinema release. Even more likely, a movie fell foul of distributors or cinema circuits especially in countries where chians were more dominant such us Britain.

Some cultural boundaries were never meant to be crossed. A country like Britain that barely saw a drop of sunshine from one year to the next could hardly be expected to appreciate the joys of endless sunshine instanced in the sub-genre of movies revolving round surfing and beach activity. This was slightly surprising given that every spy picture came with a bevy of beauties in bikinis, but the slight stories and even more miniscule budgets of the beach movies failed to find an audience in Britain. Although Beach Party (1963) with Robert Cummings and Bikini Beach (1964) starring Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello got the series off to a decent start, it was quickly downhill thereafter, the bulk of this kind of picture never shown not even the likes of The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (1966) boasting an impressive cast in Boris Karloff, Basil Rathbone, Elsa Lanchester and Nancy Sinatra.

Whether or not they might have fared better at the box office will never be know because they were not given a chance. In Britain two cinema chains – ABC and Odeon (also including Gaumont) – predominated and if a movie failed to win a circuit release on either there was little chance of it opening at all. In general, assuming a programme did not always comprise a double bill, ABC/Odeon/Gaumont between them showed around 200 films a year. Allowing that Hollywood produced 300 movies on an annual basis and the domestic industry produced about 75-100 and space had to be found for the occasional reissue or foreign blockbuster, it was no surprise that some films were just ignored altogether – never seen in Britain or received a derisory release.

This was not a situation that would be restricted to Britain. Every country in the world in the 1960s wanted to protect its domestic output, limiting audience access to American or British films by various embargoes or through the censor. Spain, for example, had 370 films on its backlog in 1962. But Britain is an interesting example since culturally it was closest to America and in theory at least there should have been no bar to movies making the Atlantic crossing.

As well as the beach party anathema, Britain film bookers proved resistant to the charms of country-and-western music, no homes found for the likes of Hootennany Hoot (1963), Nashville Rebel (1966) starring Waylon Jennings and That Tennessee Beat (1966). A variety pictures concerning serious subjects like racism, politics, drug addiction, or mental illness put paid to the prospects of, respectively, Black Like Me (1964), The Best Man (1964) – directed by Franklin J. Schaffner and starring Henry Fonda and Cliff Robertson – Synanon (1965) with Stella Stevens and Andy (1965).

Neither did stars necessarily open doors. Henry Fonda led the field in circuit disfavor with The Best Man, The Dirty Game (1966) and Killer on a Horse (1966). Also out in the exhibition cold: Act One (1963) with George Hamilton, Jason Robards and George Segal, Virna Lisi and James Fox in Arabella (1967), Who Has Seen the Wind (1965) with Edward G. Robinson, Maximilian Schell in Beyond the Mountains (1966), Ginger Rogers and Ray Milland in The Confession (1965), Rossano Brazzi and Shirley Jones in Dark Purpose (1964), Anthony Perkins in Violent Journey (1965), Robert Taylor and Anita Ekberg in The Glass Sphinx (1966), and Alec Guinness and Gina Lollobrigida in Hotel Paradiso (1965).

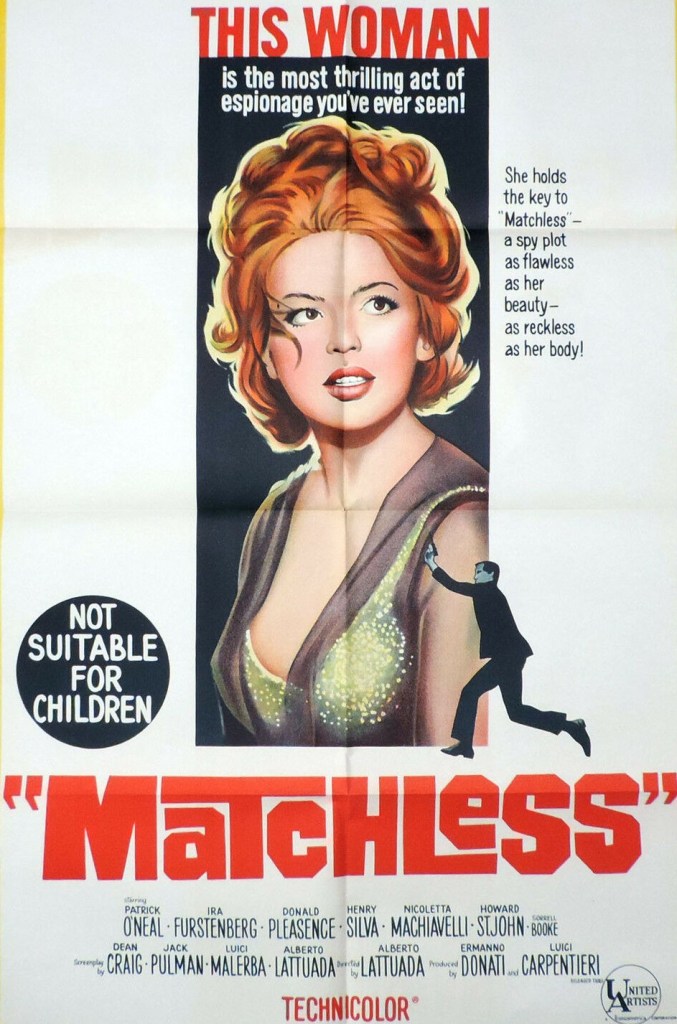

Other big names unwanted by the circuits: James Mason in Love Is Where You Find It (1967), Patrick O’Neal in Matchless (1966), Marcello Mastroianni and Pamela Tiffin in Paranoia (1965), Anthony Quinn and Rita Hayworth in The Rover (1967), Raquel Welch in Shout, Shout, Louder, I Don’t Understand (1966), Rod Steiger in Time of Indifference (1966), Troy Donahue in Come Spy with Me (1967), Angie Dickinson in I’ll Give My Life (1960), and Elke Sommer in The Wicked Dreams of Paula Schultz (1967)

On the comedy front add to that list: Jackie Gleason in Papa’s Delicate Condition (1962), The Outlaws Is Coming (1965) with The Three Stooges and Woody Allen in What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (1966). Despite headlining Jayne Mansfield, Las Vegas Hillbillies (1966) found no takers. But that was not unusual for Mansfield. Other films never considered for the circuits were Promises, Promises (1963), The Fat Spy (1966), Panic Button (1964) co-starring Maurice Chevalier, and Single Room Furnished (1968). No room was found for Jeffrey Hunter trio – Battle Royal (1965) with Luciana Paluzzi hot after Thunderball, The Christmas Kid (1967) and Witch without a Broom (1967). John Saxon – generally appreciated as a supporting actor – found no circuit support for pictures in which he was top-billed such as The Ravagers (1965) and The Cavern (1965) with Rosanna Schiaffino.

There was very low interest in William Castle gimmick-ridden horror films 13 Ghosts (1960), Mr. Sardonicus (1961) and 13 Frightened Girls (1963) and none at all in Project X (1967) while the films of Samuel Fuller scarcely got a look-in, in part due to censorship, Underworld USA (1960) the only one to get any bookings. Despite the general demand for horror, The Blood of Dracula’s Castle (1969), Blood Bath (1966), Queen of Blood (1966) directed by Curtis Harrington, and Orgy of Blood (1968) did not get onto the bookings starting grid. Nor did Michael Rennie in Cyborg 2087 (1966) or Scott Brady in Destination Inner Space (1966) or Women of the Prehistoric Planet (1966).

Tammy and the Millionaire (1967) was one too many in the previously popular series. While topping the pop music charts, Sonny and Cher were considered box office busts, Wild on the Beach (1965), Good Times (1967) directed by William Friedkin and Chastity (1967) all failing to bag a booking.

The term “shelved” had a different meaning in the United States and tended to means films which had been cancelled at the production stage, rather than completed but not finding their way into the release system. In 1969, when Warner Brothers tied up with Seven Arts, around 40 projected pictures bit the dust including Sam Peckinpah pair The Diamond Story and North to Yesterday, Heart of Darkness to be directed by Andrej Wadja, William Friedkin’s Sand Soldiers, Edward Dmytryk’s Act of Anger, Paradise from a story by Edna O’Brien, and Sentries from the Evan Hunter novel. Some movies killed off at this point would eventually be filmed: The Man Who Would Be King (filmed in 1975), 99 and 44/100% Dead (1974) and a musical version of Tom Sawyer (1973)

While not on this scale, movies were cancelled all the time. Some movies carried hefty price tags. Shirley MacLaine nabbed $1 million after a pay-or-play deal after the cancellation of musical Bloomer Girl to be directed by George Cukor. the director was also initially involved in a version of Lady L to star Tony Curtis and Gina Lollobrigida. it was scrapped in 1961 but later filmed with different stars in 1965.

Even so, the shelf of unreleased films in the U.S. was at times very crowded. Although the vast majority of studio pictures received some kind of release, either in the arthouse or drive-in circuits if not deemed commercial enough for first run, sometimes they sat around for an unusually long time. When Variety determined in 1967 that the Hollywood vaults were bulging with over 125 completed pictures, among them were several movies that would not see the light of day until well into 1968 including Dark of the Sun, Planet of the Apes, Hang ‘Em High and The Odd Couple.

Although there were circuits in the United States, they were not national nor as dominant as in the U.K. so most films managed to find a way into the system somewhere, and therefore until the likes of The Picasso Summer (1969) and The Extraordinary Seaman (1969) – as previously mentioned in the Blog – were deemed to not hold sufficient commercial attraction and were dumped more or less straight into television then the number of movies not screened was considerably lower than in Britain.

SOURCES: David McGillivray, “The Crowded Shelf,” Films and Filming, September 1969, p15-22; “Lady L Cold,” Variety, June 21, 1961, p19; “Spain’s Unreleased Backlog: 370,” Variety, May 2, 1962, p120; “Shirley Yens $1-Mil on Fox’s Unmade Bloomer,” Variety, September 7, 1966, p7; “H’wood Backlog Hefty at 125,” Variety, September 13, 1967, p3; “Courtesy of the Film Road,” Variety, July 23, 1969, p 5; “Deferred Film Deals at W-7,” Variety, July 23, 1969, p 5; “Projects Scratched at Warners,” Variety, October 22, 1969, p6.