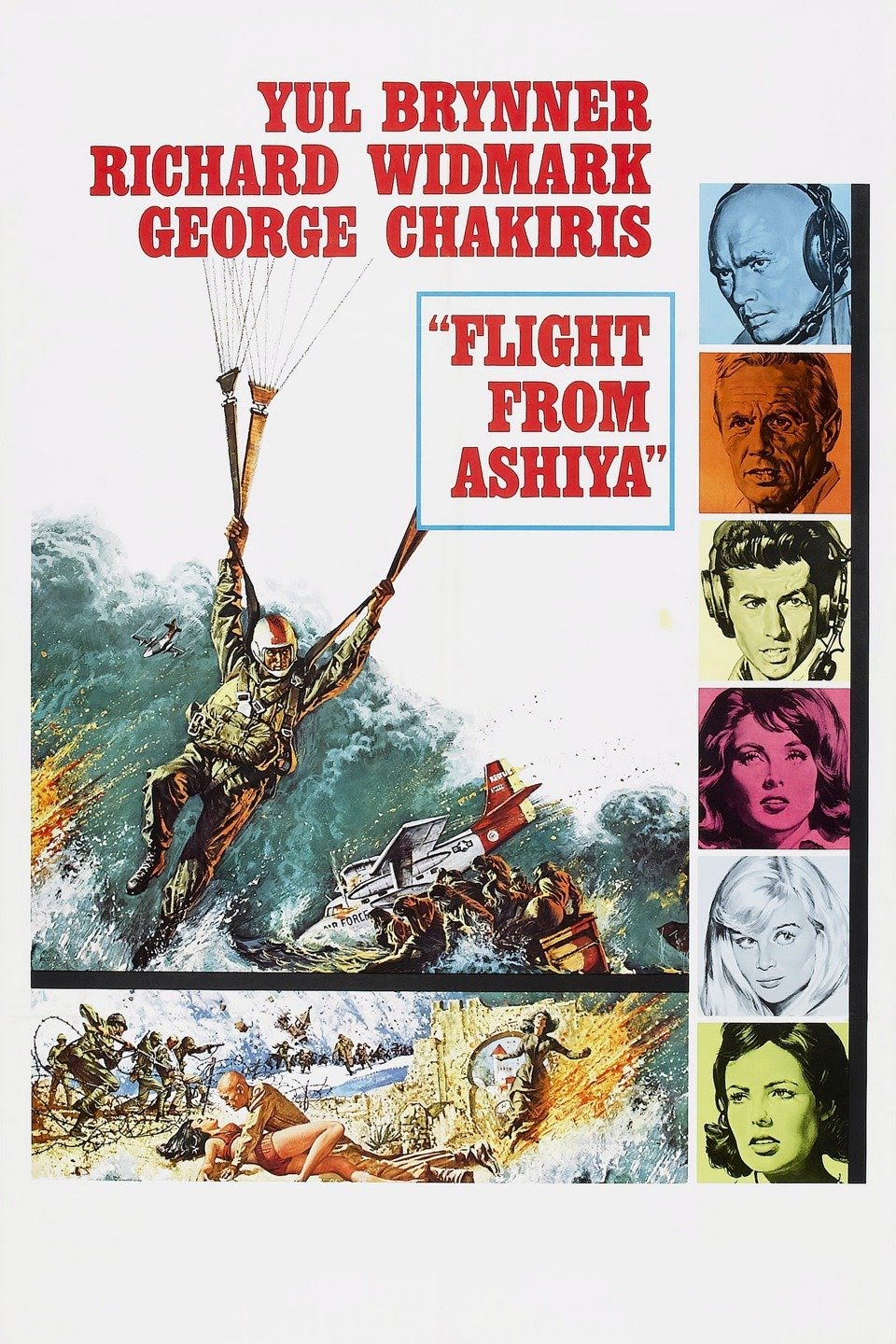

Imperialism is hard to stomach these days but at the start of the twentieth century it was rampant and as shown in this picture not just restricted to the main culprit, the British. China was Imperialism Central, round about a dozen nations including the USA and Russia claiming control of sections of the country or its produce. So they had all set up diplomatic shop in Peking. And the film begins with an early morning roll call of national anthems before this domination by outside interests in shattered by rebellion.

Just as hard to stomach, of course, was the movie mainstream notion in those days that all rebellions must perforce be put down regardless of how put-upon the peasant classes were. Audiences had to rally round people in other circumstances they would naturally hate. So one of the problems of 55 Days at Peking is to cast the rebels (known as Boxers) and the complicit Chinese government in a bad light while ensuring that those under siege are not seen as cast-iron saints. There’s no getting round the fact that the rebels are shown as prone to butchery and slaughter while the Chinese rulers are considered ineffective and traitorous.

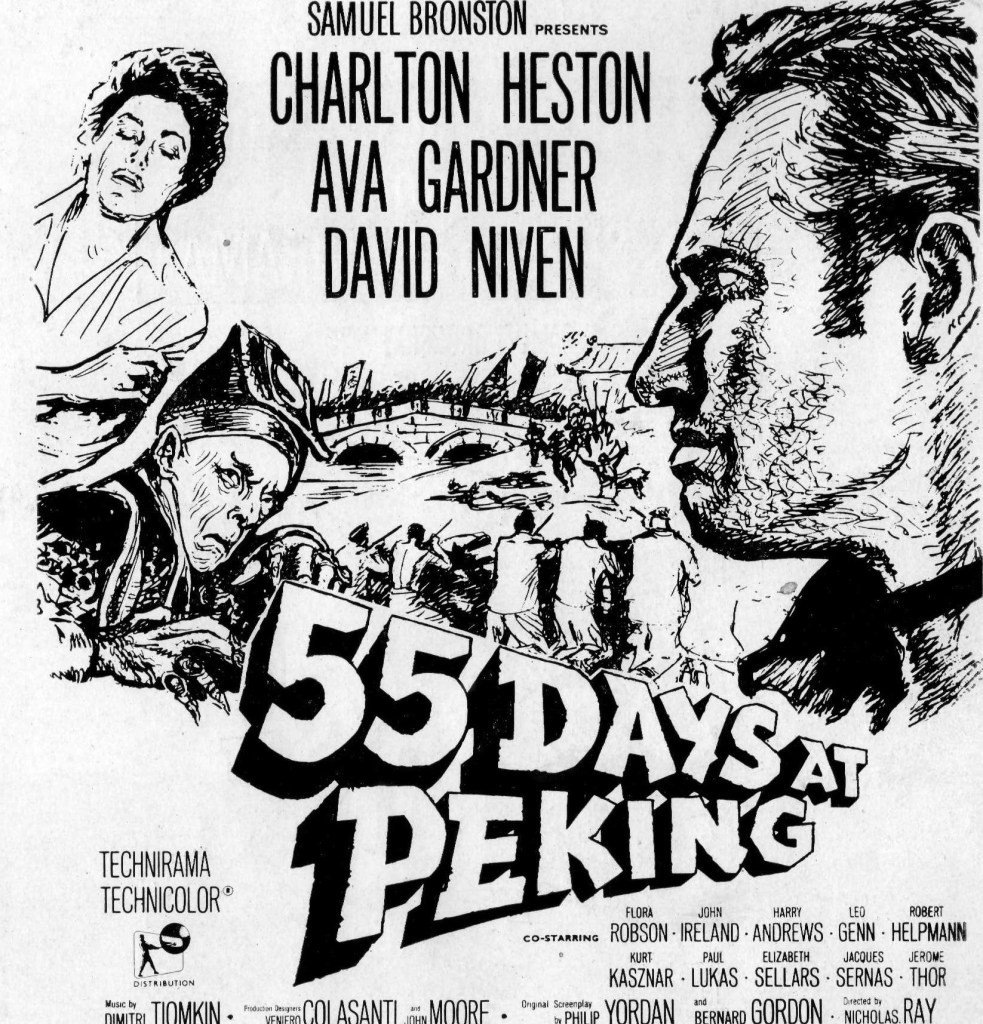

So it’s left to the likes of Charlton Heston as the leader of U.S. Marines stationed in the city to bring some balance to proceedings. “Don’t get the idea you’re better than these people because they can’t speak English,” he expounds. David Niven plays the British Consul trying to keep this particular league of nations onside while negotiating with one hand tied behind his back – “we must play this game by Chinese rules” – with the Chinese Dowager Empress (Flora Robson) while knowingly endangering his wife (Scottish actress Elizabeth Sellars, a one-time big British star) and two children. Ava Gardner is an unscrupulous Russian baroness with little loyalty to her home country.

The picture is one-part action, one-part politics and one-part domesticity, if you include in the last section Heston’s romance with Gardner, Niven’s guilt when his son is wounded in an attack and Heston’s conflict over a young native girl (Lynne Sue Moon) fathered by one of his own men who is then killed. Two of the best scenes are these men coping with parental obligation, Niven coping with a wounded son, Heston finding it impossible to offer succour to the child.

The action is extremely well-handled. The siege goes on longer than expected when the expected troops fail to arrive, tension rising as casualties mount and supplies fall low. As with the best battle pictures, clever maneuvers save the day. Two sections are outstanding. The first has Heston marshalling artillery to prevent the Chinese gaining the high ground. The second is a daring raid – Niven’s idea, actually – through the city’s sewers on the enemy’s ammunition dump. Personal heroism is limited – Heston volunteers to go 70 miles through enemy territory to get help but has to turn back when his men are wounded or killed.

There’s a fair bit of stiff upper lip but while Heston, in familiar chest-baring mode, has Gardner to distract him, Niven is both clever, constantly having to outwit the opposition and hold the other diplomats together, and humane, drawn into desperation at the prospect of his comatose son dying without ever having visited England. Gardner moves from seducer to sly traitorous devil to angel of mercy, shifting out of her beautiful outfits and glamorous hats to don a nurse’s uniform, at the same time as shifting her outlook from selfish to unselfish. All three stars acquit themselves well as does Flora Robson in a thankless role.

This was the third of maverick producer Samuel Bronston’s big-budget epics after King of Kings (1961) and El Cid (1961) with a script as usual from Philip Yordan and directed by Nicholas Ray.

All in all it is a decent film and does not get bogged down in politics and the characters do come alive but at the back of your mind you can’t help thinking this is the wrong mindset, in retrospect, for the basis of a picture.

Many of the films from the 1960s are to be found free of charge on TCM and Sony Movies and the British Talking Pictures as well as mainstream television channels. This one I noticed is available on YouTube at the point where I was reviewing it. But if this film is not available through these routes, then here is the link to the DVD and/or streaming service.