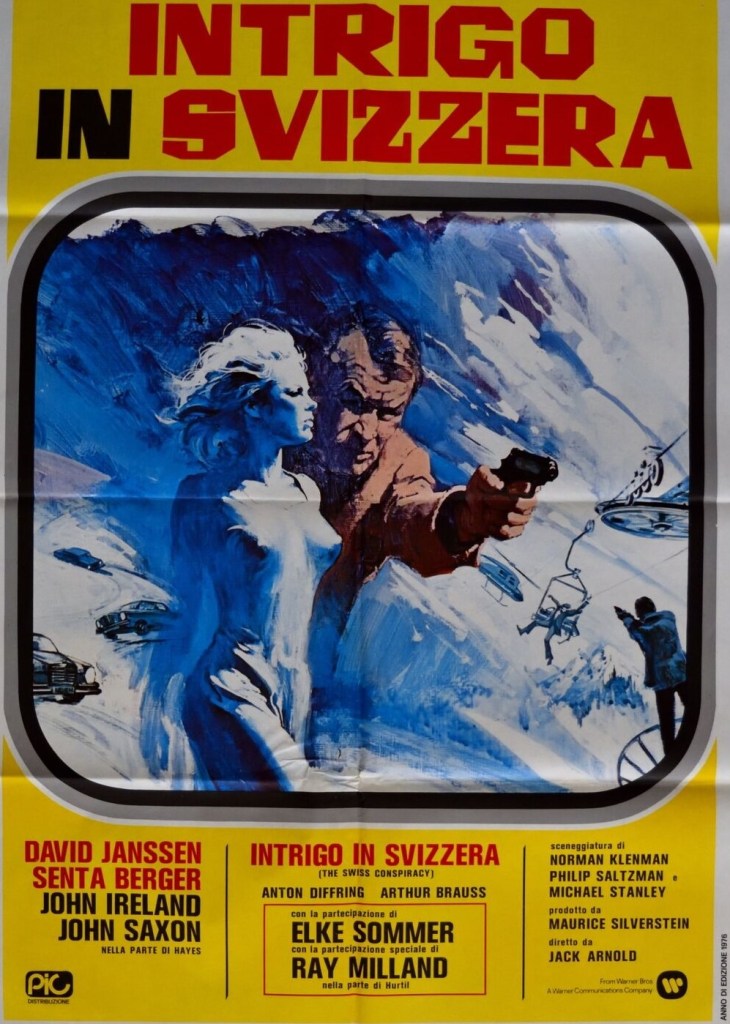

One of those thrillers that only makes sense at the end. Lazy critics, too annoyed to wait or not able to work it out themselves, take out their bafflement on the picture. Or they carp at what they see as overmuch tourist influence instead of admiring the clever use made of Switzerland’s scenic attractions, the twisty cobbled streets, corkscrew highways teetering over ravines, and the apparatus of skiing – the chug-chug trains and lifts.

Attractive too for the cast. You might put me down as overly fond of leading lady Senta Berger (Bang! Bang! You’re Dead! / Our Man in Marrakesh, 1966) but I’m equally appreciative of the casual charm and realistic qualities brought to the screen by the underrated David Janssen (The Warning Shot, 1967). And that’s before we come to Elke Sommer (The Prize, 1963) and veteran Hollywood star Ray Milland (Hostile Witness, 1969), not to mention character actors John Saxon (The Appaloosa / Southwest to Sonora, 1966) and John Ireland (Faces in the Dark, 1961).

Former U.S. Treasury Agent David Christopher (David Janssen) is called in by Swiss bank owner Johann Hurtil (Ray Milland) to investigate a threat to expose the clients hiding behind the country’s infamous secret numbered accounts. Five clients, in particular, have been targeted including the glamorous Denise Abbott (Senta Berger), whom David first encounters in what would in other circumstances be deemed a clever meet-cute with the woman getting the upper hand.

One client is already dead, murdered in the opening sequence, as a warning. Of the others, Robert Hayes (John Saxon) is a mobster depositing illicit gains for money-laundering purposes, Dwight McGowan (John Ireland) a shady businessman on his last legs, while Kosta (Curt Lowans) equally operates in the shadows. And all is not well with the bank deputy Franz Benninger (Anton Diffring), involved in an affair with another client, Rita Jensen (Elke Sommer). On top of that, Swiss cops are on the trail of Hayes and hit men are tailing Christopher.

Christopher quickly surmises that the victims have been targeted for their undercover dealings, even the uber-glam Denise is blackmailing a former lover. But Hurtil, fearing a public and media scandal, and for whom the gangster’s demands are a mere drop in the ocean compared to the bank’s overall wealth, decides to meet their terms, which is payment of 15 million Swiss francs (equating to several million U.S. dollars, I guess) in uncut diamonds.

But before that we have a punch-up and shoot-out in a parking garage, a chase on foot on those famous narrow cobbled twisty streets with a speeding car giving the thugs unfair advantage, a race of seduction a la On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1970) along those aforementioned treacherous mountainous roads, a literal cliffhanger in the vein of The Italian Job (1969), and one of those luscious romances beloved of the upmarket thriller (think The Thomas Crown Affair, 1968).

While Christopher is painstakingly putting together the clues and keeping the suspicious Swiss police off his back and avoiding being killed, there’s a deadline to meet, the usual race against time, while the audience is having to fend off a surprising number of red herrings.

It’s not only glamorous, it’s short, and there’s more than enough going on, characters played by interesting actors, to keep the viewer involved. And I defy you to guess the ending. So, enough thrills, sufficient mystery, great scenery, and a female contingent (even Christopher’s secretary fits that category) with brains to match their sexiness who appear to have the upper hand in relationships with the opposite sex.

This is David Janssen at his best, that outward diffidence concealing a harder inner core, exuding a guy-next-door appeal that was never properly utilised by Hollywood, who preferred him just to reveal character by squinting. The scene where he takes in the extent of the luxury of Denise’s hotel penthouse is one of those that, while not knocking on Oscar’s door, demands true acting skills. He’s never in your face, and the camera loves him for it.

Of course, Senta Berger, what can you say, another under-rated actress never given her due in Hollywood, here finds a plum role that allows her to switch from confidence to vulnerability at the drop of a hat. John Saxon and John Ireland, as ever, are value for money. And Ray Milland keeps the show on the road.

A modern audience would be more at home with the multiplicity of plot angles and probably worked out in their own heads all that couldn’t find a place on screen, ensuring that what seemed like plot holes were anything but.

Jack Arnold (The Creature from the Black Lagoon, 1953) handles the scheming and dealing with ease. Norman Klenman (Ivy League Killers, 1959), and two television writers in their movie debuts, Michael Stanley and Philip Saltzman, wove the intricate screenplay.